![]()

Chapter 1

The Household Searchlight Recipe Book

Lora E. Smith

I COME from a place of dumpling makers. I live in an economy built on fried squirrel, frog legs, fruit cobblers, and the shared work of women’s wisdom and hands. A region shaped by a piecrust made of 3 cups flour, 1 cup lard, 2 teaspoons of salt, and ½ cup or so of water. I know these things because they are scribbled down in the margins of my great-grandmother’s cookbook.

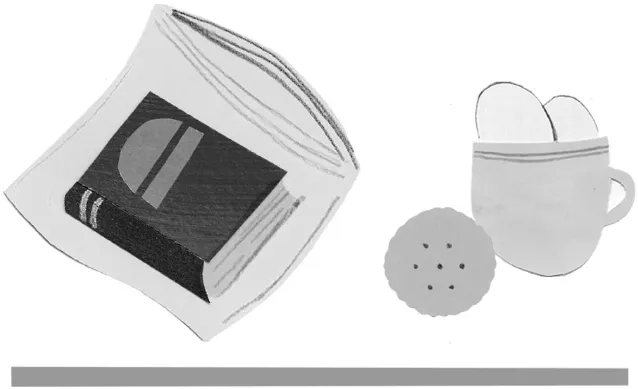

I was gifted a 1938 copy of The Household Searchlight Recipe Book by my mother after my second child, a son, was born. I’d just moved home to eastern Kentucky for what I’d sworn was going to be the very last time. The cookbook originally belonged to my great-grandmother and namesake, Lora Sharp, and had been handed down to my grandmother and then to my mother. It now rests inside a Ziploc bag I keep on the top shelf of my pantry.1

The Household Searchlight Recipe Book was part of a series of cookbooks targeted at women living in towns of ten thousand people or less released during the 1920s through the 1940s. The cookbooks were published by the Topeka, Kansas–based Household Magazine, a monthly women’s magazine that promised to address the needs of its (largely white and rural) readership. “The Household Searchlight” was a regular column in the magazine that tested and rated new consumer products for the home.

The February 1926 issue of the magazine has the author of that column testing a new Nesco stove with the opening proposition that “a stove needs to perform so many duties in a kitchen that the selection of a new one is indeed a problem.” The same issue also contains a full-page advertisement for Jell-O that excitingly proclaims, “So easy to prepare that even the children can make it.” And an editorial titled “Women at Home—and Out of It” discusses technological advances alongside promoting policy change to increase immigrant labor as an “economical” means for relieving the demands of domestic work on white women starting to enter jobs in a changing economy.2 Domesticity, home economics, and to a larger extent the changing role of rural white women in an industrializing workforce had become modern problems in need of modern solutions. In this case, solutions included the exploitation of immigrant labor, processed foods potentially prepared by children, and technology in the form of expensive consumer goods like new washing machines and vacuums.

The Household Searchlight Recipe Book in my possession was developed by open-sourcing recipes from its national readership through a reported one thousand questionnaires that were mailed to identified subscribers, “who were known to be especially interested in food preparation.” The resulting book was divided into a “General Directions” section organized by technique and a “Recipes” section organized under twenty-two different tabs categorized by type of food. The cookbook’s foreword lets the reader know that expert help is close at hand:

The Household Searchlight is a service station conducted for the readers of The Household Magazine. In this seven-room house lives a family of specialists whose entire time is spent in working out the problems of homemaking common to every woman who finds herself responsible for the management of a home and the care of children.3

The recipes come from women such as Mrs. J. F. Deatrick of Defiance, Ohio, who shares her self-proclaimed “Prize Winning Recipe” for Turnip Cups.

Select white turnips of equal size. Pare. Cut a thin slice from the top of each, so turnips will stand when inverted. Parboil in salted water. Drain. Beginning at the bottom, hollow out each one in the form of a cup. Mash the portions of turnips which were removed. Combine with an equal quantity of chopped meat, cheese, or fish. Season to taste. Moisten with a little cream. Place in a baking pan. Bake in moderate oven (375 F) about 25 minutes. Serve with roast or boiled mutton or beef.

Mrs. R. J. McLin of tiny Hazel Green, Kentucky, shares a Pineapple Fluff recipe that includes egg whites, whipping cream, crushed macaroons, jelly, crushed pineapple, diced marshmallows, and grated sweet chocolate.

Combine egg whites and jelly. Beat until stiff. Fold in stiffly whipped cream, pineapple, and macaroons. Add marshmallows. Pile lightly in glasses. Dust with chocolate. Serve ice cold. If desired, lady fingers or vanilla wafers may be substituted for macaroons.

Virginia Cooper of New Orleans, Louisiana, an urban anomaly in the collection, is especially prolific, making an appearance in almost every section to share dishes like Creole Gumbo and Creole String Beans. There are other regional dishes sprinkled throughout the book, including recipes for tomato gravy, hominy, hassenpfeffer, and chili con carne.

But the copy pressed into my hands by my mother was not a standard edition. Brown tattered edges of papers stuck out in every direction, and the spine of the book was almost threadbare. Upon opening up its black embossed cover that shows a small home nestled beneath trees, I discovered that my great-grandmother had been using the cookbook as a personal diary in which dates, mundane happenings, and important events were recorded alongside family and community recipes.

Sometimes the included recipes are transposed on top of the cookbook’s “official” printed recipes, my great-grandmother’s handwriting completely covering the front and back covers of the book as well as taking up white spaces of pages therein. Scrawled in the margins like graffiti and taped to the backs of pages like wheat-pasted city flyers, her family’s and neighbors’ recipes take up room throughout the cookbook and often stand in contrast to the printed recipes that signal a middle-class and pre-Depression abundance. A recipe written in blue ink on a piece of yellow paper taped over an Index page shares a Depression-era pie that approximates crackers for cooked apples.

Ritz Cracker Apple Pie.

Bring to a boil.

2 cups water. Add

1 ½ " sugar.

1 stick butter

2 ½ teaspoons cream tarter.

½ " nutmeg.

After this mixture has come to a boil, drop in

26 to 30 whole Ritz Crackers.

Cook 2 minutes.

Then pour in unbaked pie

shell that has been sprinkled

with cinnamon, bake 450

for 20 or 30 minutes, or until

brown.

Some of these recipes are noted as Lora’s, but most are attributed to other women—family members, friends, and neighbors. Dot’s Chili, Mrs. Logan’s Prune Cake, and Mrs. Jack Skinner’s Icicle Pickles share equal top billing. There is variety but also duplication in many of the recipes. There are multiple pickle recipes, layer cake recipes, and hot roll recipes. Some are almost identical, but all are attributed to different women in her community and show respect by being chosen as important and “good enough” to be saved.4

And then there are the journal entries. Dates, places, names, events. My great-grandmother utilized the commercially produced cookbook as a private space to chronicle her life, making visible a network of friends, family members, neighbors, and daily occurrences, tucked in somewhat haphazardly among the chattering recipes from strangers. The journaling allows me to create a sense of chronological order to her days and may have served as a way for her to make sense of her life—one marked by loss from an early age.5

Lora Skinner was fifteen years old in 1903 when she died during childbirth on her family’s farm in Whitely County, Kentucky. Her parents, Alice Hatfield and Greenberry Skinner, were raising four children on a subsistence farm located up a holler near Rockholds, Kentucky, when Lora became pregnant out of wedlock. The father was unknown, or at least his identity was kept from the rest of the family and treated as a shameful secret. Even in my generation we were told not to discuss it. On the recorded birth certificate, the father of the child is listed as John Sharp, a fifty-four-year-old neighbor who lived in the holler over from the Skinner farm. It’s possible that he was the father. Or maybe the father was John’s twenty-year-old son. What tugs at me is whether this was a pregnancy resulting from an act of young love or from the rape of a teenage farm girl left to fend for herself amid long days of labor.

Upon birth, my great-grandmother Lora Sharp was given her dead mother’s first name and the surname of the man who reluctantly claimed her, and was raised alongside her aunts and uncles on the family farm. Her mother is not buried in the hilltop family graveyard in Woodbine, Kentucky, where Alice, Greenberry, and their other three children rest. In fact, after searching historical records and physically searching the family cemetery and surrounding cemeteries in the community, I have been unable to locate any grave at all. Lora Skinner disappeared from the family after giving birth to her daughter, and I’ve accepted that her name is likely as close as I’ll ever come to her.

Seven-year-old Lora Sharp was enumerated incorrectly in the 1910 Census under her mother’s name, Lora Skinner, and was also mistakenly listed as a niece rather than a granddaughter. The 1910 Census also lists several nonfamily members as “boarders” living in the house with Lora and her family. One boarder in the home is Bradley Brooks, a seventeen-year-old African American boy born in Kentucky. Bradley is gone from the Skinner home by the 1920 Census, and I have yet to locate him again in historical records.6

At nineteen, Lora Sharp moved off the farm to the railroad town of Corbin, Kentucky. There she married her first husband, an engineer on the L&N Railroad with whom she had her only child, my grandfather Ora Moss Smith. Lora divorced several years later and, according to her cookbook diary in an entry that reads unceremoniously, “Bob and I was married May 4, 1936,” became Mrs. Bob Meadors. At the same time, Lora took in Bob’s son Dillard to raise. Everyone on my side of the family agreed that Bob was from Ohio, a polite way of saying that no one liked him. The two remained married until Lora’s death in 1975.

The original diary entries that are visible in the cookbook mostly revolve around my grandfather Ora Moss Smith’s time deployed during World War II. Lora writes as an anxious mother of an only child documenting letters, wired messages, and bits of news they received from or about my grandfather. My grandfather, thankfully, came home, intact and honorably discharged with a Purple Heart, but suffering with malaria and signs of PTSD from his deployment in the Philippines. An entry written vertically in looping cursive near the spine of the front cover reads, “Ora come back from San Diego, Calif. December 15, 1942 Discharged.”

However, an entire page of dates and journaling has been covered by two pieces of butcher paper glued on top. One of the brown pieces of paper has an orange cake recipe and the other a recipe for fermenting pickles with wild grape leaves added as a tannin-containing agent, a mountain trick to keep pickles crisp in the crock. Maybe she didn’t care to lose some things to a good pickle recipe. But judging from the few dates and scribbles that are visible beneath the butcher paper, I believe Lora was writing multiple entries about time periods she purposely wanted to cover up because they chronicle her first marriage. I worked with an archivist at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Wilson Library to try and remove those pieces of butcher paper, but with no luck. Lora chose to paste over that part of her life, and I am forced to respect that she didn’t want me to see what she didn’t want me to see.

But something else is happening on the inside cover that puzzles me. Lora documents her birthday every year usually with some piece of quantitative data attached to it: where she lived, what she weighed, the destination of a trip, or a visit by a family member or friend that occurred. It’s odd, but I believe what she was ultimately doing was marking time. And it’s not lost on me that her birthday each year also commemorated her mother’s passing, a passing she had no way of outwardly memorializing because there was no graveside to visit and the circumstances of her birth and her mother’s death were muffled in the family’s silence.

Through her marked and altered cookbook, Lora actively defined a regional identity and economy grounded in Appalachian foodways through her choices of go-to recipes. Immediately noticeable upon encountering the cookbook are the dog-eared pages and brightly inked circles and stars surrounding printed recipes in the cookbook she liked and, I assume, used often. They include many of the meals I grew up with as a young child during family suppers in the 1980s. Likewise, almost all of the circled recipes are familiar southern or Mountain South ones, or they are adaptable enough to her home, based on readily available ingredients. In the Game section, Fried Squirrel and Squirrel Stew are circled with vigor, both recipes hailing from women in Appalachian Ohio. Squash dishes are starred and highlighted over and over. Several familiar quick breads in the Breads section stand out, and Frog Legs is the only thing circled in the misidentified Fish section.

Recipes she added that are especially stressed are Lora’s “dumplins” recipe and her pie crust recipe. Dumplins are so important that a reminder of what page number they are on—it’s page 256—graces both the front and back inside covers. The recipe is written in fuchsia ink as follows:

(Dumplins)

2 cups flour

Stir make hole

2 table spoons lard

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon Baking Powder Powder

2 eggs in tea cup.

Finish up with water & make your dough.

That is Dumplins

What you’re supposed to do afterward to complete the recipe is not clear, so the women in my family learned directly from one another or improvised and innovated to our own taste.

Taken together, the many voices of the women held inside the worn leather cover—Lora’s voice, the voices of women in her local ...