![]()

CHAPTER 1

Product Emotions

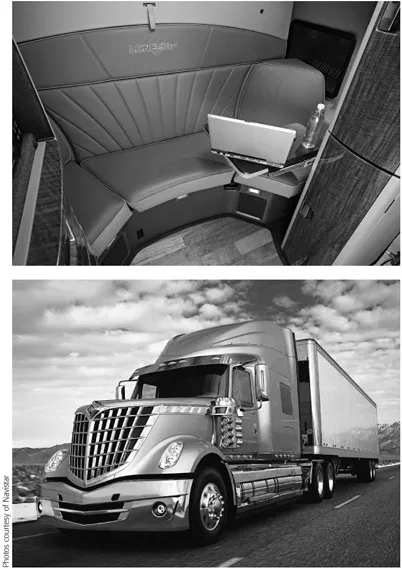

We have all seen large “big-rig” trucks rambling down the interstate. Each of those 40,000-pound vehicles is a small business on wheels, driven by an employee or by the business owner himself. For trucks, as with other small businesses, business profits require efficiency. Fuel-cost increases have made profit margins slimmer than ever before, and weight restrictions (on the whole truck—cab and trailer) mean that every pound counts. Money is made delivering payload, so the weight in the cab is minimal, maximizing payload weight.

The truck is not only a business, but is also a home—a very small home, roughly the floor area of a two-person tent, a mini room in which the driver needs to sleep, eat, and change clothes, and also watch movies, read, play video games, and do deskwork. There is no separate living and sleeping area, no place to change or freshen up, few places to store belongings, and no place to prepare even a sandwich. This is where the driver spends his time while on the road.

The more that goes into that home to make the driver’s life better, the more it both costs and weighs, reducing business efficiency. Long-haul truck interiors have therefore been designed as efficient, lightweight spaces with minimal creature comforts, allowing drivers just enough space for sleep so they can get back on the road. Even for those U.S. drivers who own their vehicle and sacrifice some fuel economy for the classic look of an American truck, the vehicle interior remains sparse.

What had been overlooked, or not recognized as important, was the opportunity to design the truck interior to be more than an efficient business tool. The drivers consider themselves professionals, making sacrifices to be away from family and friends. The life of a trucker can be tedious, lonely, and uncomfortable. Employee turnover is greater than 100 percent per year among fleet drivers, which means that drivers’ lifestyle needs are significant to the industry.

In 2008, Navistar’s International Truck, a longstanding brand that had become known only as a basic workhorse, introduced LoneStar, a different kind of long-haul truck. New management at Navistar recognized the underlying dual needs of those in the trucking profession: the need to keep costs low with efficient business tools along with the need to transform a monotonous and stressful task into a more comfortable and enjoyable profession. Navistar understood that the trucker longs for family and friends, needs a place to unwind, wants a good night’s sleep, and requires simple, convenient meals. Navistar realized that truck drivers lacked positive emotional experiences on the road. LoneStar answers the duality of truck industry needs, for LoneStar is a paradigm-shifting truck that fulfills emotional desires while also delivering superior performance.

LoneStar is a bold, classic-looking truck, with styling features that hark back to the 1930s and ’40s, while clearly setting a styling trend for the 21st century. Truckers love chrome and LoneStar uses chrome elegantly and plentifully on the exterior, with chrome just about everywhere chrome can be. Its bold, pronounced grille gives the truck command of the road, and pride in the ride.

On the inside, unlike traditional trucks with cramped, spartan living spaces, LoneStar’s interior is more like a cabin in a private jet. Its interior incorporates amenities that have not been available in standard trucks: features for cooking, eating, sleeping, and relaxing. Unlike other trucks with two bunks, there is a full-sized bed in LoneStar; it folds up Murphy-style, revealing a crescent-shaped couch. A kitchenette with food storage, microwave, and refrigerator allows for simple meal preparation, and a pullout table provides space to eat and work. Airline-like overhead storage keeps the cabin neat and organized. Hardwood flooring, a television, and a seven-speaker Monsoon sound system complete the living experience.

The interior design and its features make the driver feel professional, successful, and comfortable, all in a roughly 4-by-7.5-foot space. At the same time that the truck is specifically designed for the trucker’s emotional and lifestyle desires, business needs such as fuel economy were taken seriously. At its introduction, LoneStar was arguably the most fuel-efficient long-haul vehicle on the planet, the most aerodynamic for headwinds and winds from any direction, because winds do come from all directions.

It may be no surprise that Navistar had plenty of pre-orders on the truck. The surprise is that truck drivers also stood in line at the truck’s introduction to have the LoneStar logo permanently tattooed to their arm (in some cases both arms) without yet owning or even having driven the vehicle. That’s a truck that was built to love! LoneStar is much more than a great truck. A functional truck designed to offer emotional opportunities like no other, LoneStar is also a means to re-invigorate and reposition Navistar’s entire brand.

FIGURE 1.1 Interior (birds-eye view from above) and exterior of innovative LoneStar long-haul truck by Navistar’s International Truck brand.

Obviously, most companies would want their products to rouse customers as successfully as LoneStar has. Rather than creating products that themselves captivate customers, many companies attempt to build interest through loyalty programs, catchy campaigns, or other add-on programs. Odd as it may seem, it is quite common to attempt to engage customers by doing anything but changing the product itself!

This is what Navistar used to do. Formerly, their strategy was to make functional, cost-effective products. Engineers made the product for its functions rather than to serve emotional needs; when trying to sell it, the sales group used emotional appeals, hoping to interest customers. Instead of competing for the top-loved brand, they competed for the lowest-margin commodity. This is the way many companies have long treated emotion, as something to evoke after the product is built in order to make the sale. This is a fundamentally different approach from meeting an emotion-based opportunity head-on.

Today Navistar makes its trucks both for functional purposes and to fulfill emotional ones. Driving a truck from Cleveland to Kansas City, a driver delivers the goods to the destination. Driving a LoneStar also allows the trucker to enjoy the pleasure of getting there. If the truck did not get the goods from Cleveland to Kansas City, nobody would be satisfied, no matter how exciting the truck is, not the trucker nor their client. The result would be negative emotions such as anger, loss, neglect, or incapability.

Meeting functional needs is a requirement to prevent negative emotions, but success goes far beyond preventing negative emotions. People love a product not only because it serves their task, but because it serves emotions related to their task as well. For the trucker, just getting from Cleveland to Kansas City is not enough. The trucker prefers to get there in a way that makes him or her feel proud, powerful, comfortable, professional, and successful. There is more to the experience than the functional task; the lifestyle benefits of the experience are important as well.

Navistar aggressively and consistently used an emotion strategy to drive development of LoneStar. Throughout Built to Love we revisit Navistar’s transformation from being commodity driven to emotion driven, uncovering customer-desired emotions and translating those into a product emotion strategy. In Chapter 7, we demonstrate how that strategy produced a series of exciting new trucks, including LoneStar, partly through a high-emotion, visual form language.

Navistar is one of many case studies explored in Built to Love. Not all companies understand that emotions cannot be an add-on, an afterthought, and still engage their customers. Emotions that powerfully engage customers are those that are core to the very reasons to make the product in the first place: because it will be a product that customers value. A product built to love.

Product Emotions Everywhere

To recognize the relevance of emotion in products other than trucks, let’s ask a basic question: Why do people buy things? It is an essential question to business, a basic concept that may seem simple to answer. Yet many companies do not truly understand why customers are willing to spend extra for one product when it accomplishes the same tasks as a cheaper alternative. Why are customers fanatically loyal to one product yet indifferent to another?

So why do people buy things? Customers purchase products both for what the product does for them, namely, “product functions,” and also for how the product makes them feel, what we call “product emotions.” Consider cars, for example. People require transportation. One function of cars is to provide the ability to move us from place to place. Customers also buy and use cars to fulfill emotional desires in addition to functional needs. Some want to feel well taken care of, so they especially enjoy luxury cars replete with comfort features such as leather seats, high-end audio, and cup holders that keep their morning coffee warm. Some want to feel “green” with a car that reduces the carbon footprint, even at added cost. These non-functional attributes create emotional value in the vehicle, fulfilling emotional wants. People buy products that make them feel better or safer or prouder.

Consider an example of a smaller product that you might use every day. When the iPhone came out in 2007, other products such as the Palm Treo already met all of the core functional deliverables of the iPhone. But the iPhone, with its ease of use, sexy interface, and beautiful aesthetic, led people to feel empowered, joyful, and well cared for. The iPhone also overcame the significant impediment of being relegated to a single service provider. Consumers have been amazingly willing to leave their existing service providers to become iPhone users.

The iPhone initially succeeded not because of its functionality but because of its product emotions: the emotions people felt when they saw, touched, and used the product, and the way they integrated it into their lives and lifestyles. The result was love. One iPhone owner recently told us, “It’s not perfect, but I love it.” Similar phrases of love are echoed in various ways among iPhone customers and by Apple customers in general.

A Product Only for Emotion

Possibly the ultimate “how it makes me feel” product is music. There is no functional need fulfilled by music; music is all about emotion. Music makes you feel happy or melancholy, energetic or restful. Music can connect you to memories and experiences. Remember the school dance when you first heard “Free Bird,” or the time on the beach listening to Bob Marley, or the Bach minuet they played at your wedding? The desire to hear music and feel those emotions results in an industry valued in tens of billions of dollars.

The emotion of music is integral to many experiences such as movies, where the suspense, happiness, and romance are foretold and amplified through music. How menacing would Darth Vader be without the deep repetitive horns in minor key announcing Vader’s presence? Close your eyes when you listen, and you feel Vader even without seeing him. Or how exciting would Indiana Jones’ escape-from-certain-death be without the contrasting upbeat, energetic, and frenetic iconic tune in major key? The musical pieces for these two movies were written by the same composer, John Williams, who clearly understands how to use music to create, mold, and direct a range of emotions.

Emotion and the Senses

Any product that elicits an emotional response must reach a customer through one or more of the five senses. To experience a product is to touch, use, see, feel, or taste it. Every time we touch, use, see, feel, or taste the product, we react to that experience with emotion, feel something inside that makes us enjoy or resent or desire or abhor the experience. Products that are not perceived by any of the senses will not directly convey emotion. For example, engine parts will have a purely functional role if they are never touched or seen or smelled or heard by a person, even though the engine as a whole produces a hum and vibration that excites the driver.

Any product with which a person interacts has the potential to deliver emotion. With music, the sense of hearing is all that is needed to capture the core product emotion. Yet emotions, positive or negative, can be amplified when delivered to more senses, such as adding a visual element to the music. Classic album artwork is, at times, revered to the level of the music itself. Music videos, which combine the visual and the auditory, are today core to the music industry. The encounter with sound, art, and motion work in concert, providing at its best a heightened emotional experience through a perfect blend of the senses.

FIGURE 1.2A Webkinz stuffed animals (well-loved collection of Ben and Joshua Cagan).

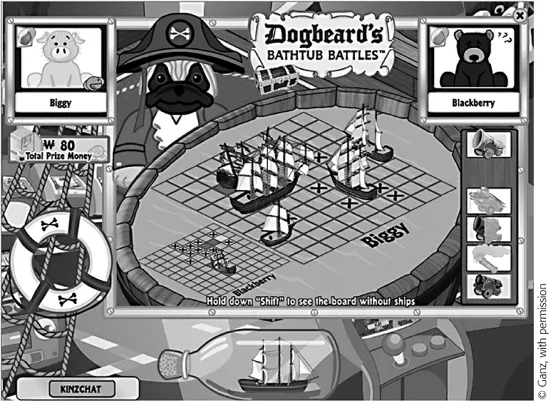

Or take a simple stuffed animal, which reaches customers through its visual appearance and quality of touch. Both elements, the appearance and the feel, can be manipulated in sync to achieve emotional goals. The fur of an aggressive-looking stuffed tiger might feel bristly, while the fur of a cuddly-looking tiger feels soft.

Beyond visual appearance and physical sensation, how can a company that makes toys give a turbo-boost to the simple stuffed animal, already the ultimate emotional connection for young children? Toy manufacturers have found ways to add technology to stuffed animals, connecting with more senses. Tickle-Me-Elmos that talk and vibrate remained popular for a decade, with hordes of people standing in line for holiday purchases.

And yet, as much as the extra technology in Elmo offers the surprise and joy for the first weeks or months, few children carry that Elmo or any other tech-laden toy with them through every night, every car ride, every visit to the store, every doctor’s office for comfort, as they do with their favorite, simple stuffed animal. How can a company create a more ongoing stream of emotions for the traditional stuffed animal?

FIGURE 1.2B Screenshots from webkinz.com, which depict the virtual version of the physical stuffed animals in their room, and provide games for kids to play.

In 2005, Ganz, a Canadian company headquartered in Woodbridge, Ontario, added a whole new dimension of sensory experience to stuffed animals, merging the ultimate “lovie” with the ultimate game forum to create Webkinz. Webkinz are soft, adorable, stuffed animals—cuddly koalas, plush pugs, cute kittens—that can be loved and dragged around like any other stuffed animal. Open the tag on its collar and go on the Internet to www.webkinz.com, type in a code, and a virtual version of the animal appears. A child sets up a user name that associates with the code, names their animal, and they can spend hours upon hours playing games (some educational), looking for gems, cooking, buying virtual clothes and toys for their pet with virtual dollars they earn playing games, and tending for the well-being of their pet.

With in two years and without advertising, over a million Webkinz users were registered. In what had been a declining industry, Webkinz sales have continued to grow steeply, reaching a broad range of children, most of whom have more than one Webkinz pet. Webkinz are a somewhat new craze, but unlike Cabbage Patch dolls and other crazes that are static, Webkinz have a dynamic element that expands the interactive pleasure of the stuffed animal experience with the exploration of new games, accessories, and actions, in addition to the basic stuffed animal that itself connects emotionally to the children.

All Ganz needs to do to keep kids coming back for more is to update activities on its website. Kids connect to Webkinz in a deep and emotional way, expressing joy, love, enthusiasm and more, and the cost margin for Ganz is minimal, producing low-cost physical toys and creating, maintaining, and updating a website.

Emotions and the Web

The web world is filled with all kinds of products that provide services and also connect emotionally with customers. Amazon and eBay satisfy the desire for non-invasive shopping for anything and everything you might want, with the ability to window-shop from the comfort of your home. With its maps, Google offers the adventure of exploration by providing directions in the physical world, and Google Maps echoes the experience with enjoyable exploration of the software itself: street views, user images, Wikipedia data, data overlays, and more.

Facebook and YouTube facilitate emotion by connecting people to one another and encouraging us to talk about whatever we want to talk about, typically issues or items about which we feel strongly (again, emotion). All of these products connect to our lives via the capabilities that the products enable, and how much they mean to all the i...