![]()

Chapter 1

A Way In: The Public Relations of New Deal Black Citizenship

We have fought America’s cause of freedom, of Unity, of Imperialism, and of Democracy!

. . . But, Are We Americans?

—Moss Kendrix in the Maroon Tiger

The public relations counsel, then, is the agent who . . . brings an idea to the consciousness of the public.

—Edward Bernays, Propaganda

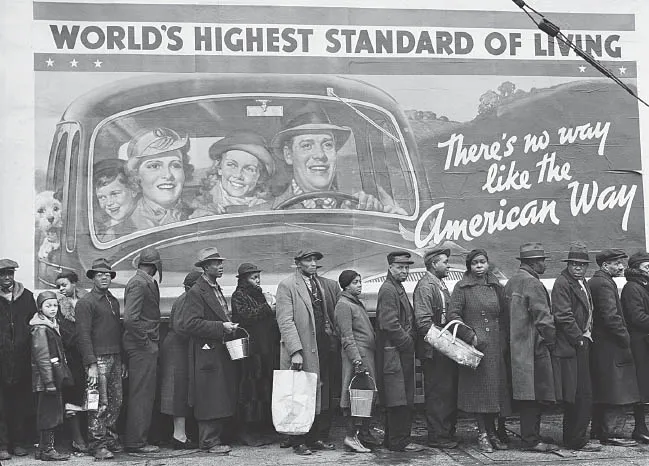

In 1937, eight years into the Great Depression, Life magazine published a photograph taken by Margaret Bourke-White, a noted documentary photographer. The black-and-white photograph depicts how a great many African Americans experienced the worst economic crisis in U.S. history (Figure 3). The documentary image shows black men, women, and children lined up, waiting to collect food and clothing from a relief agency. Several among them hold empty bags, pails, and buckets to carry away the much-needed goods they hope to collect. Others brought only their “hungry stomachs.” The African Americans pictured were residents of the “Negro” quarter of Louisville who narrowly survived the recent flooding of the Mississippi River: “refugees,” the magazine dubbed them. In the photograph, a large billboard serves as the background: it pictures an exuberant, well-dressed, white family of four and their terrier crowded into an automobile that the smiling father figure steers through a rolling countryside. One might imagine this is a family enjoying a Sunday drive after church. The wholesome cheeriness of the billboard images gives it the appearance of being in full color, despite the black-and-white medium of the photograph. Written across the billboard’s top in large block letters is “WORLD’S HIGHEST STANDARD OF LIVING,” and in script letters to the right of the car is written the declaration, “There’s no way like the American Way.”1

Figure 3. The American Way, Margaret Bourke-White photograph, 1937. Getty Images.

Bourke-White’s photograph is a composite of key occurrences that defined the Depression era. Most apparent, the photograph is a visual representation of hardship. The juxtaposition of the billboard and the downtrodden black “refugees” lined up before it symbolized a dramatic decline in the “real world” American experience. Erected as it was in the soil of the depressed South, the billboard seemed more indicative of the prosperity and “good times” that characterized the previous decade. Behind the queue of unsmiling, beleaguered-looking, African Americans, the cheery tableau is especially mocking—a colorful and gay backdrop for a bleak and tragic play. The clashing images in Bourke-White’s photograph, of white bounty and black need—each of which, the image suggests, is the “American Way”—emphasized the separateness and severity of blacks’ economic plight during the Depression.

In addition to being a record of blacks’ Depression-era experience, the Life photograph is an artifact of the phenomenal expansion of public relations during the 1930s, in large part as a response to the nation’s economic crisis. When she took the photograph of black Louisianans, Bourke-White worked on behalf of the Farm Security Administration (FSA). One of the many New Deal agencies established to spur recovery during the Depression, the FSA addressed issues of rural poverty exacerbated by the Depression. The agency employed a team of first-rate photographers to roam the country taking pictures of the nation’s poor and displaced agricultural workers. The FSA photography program represented the Roosevelt administration’s embrace of public relations to shape public opinion concerning its experimental economic and social programs. The New Deal allowed for government involvement in economic matters to an unprecedented degree, which threatened corporate interests. For their part, industrialists devised public relations campaigns to revive trust in the free enterprise necessary to their survival. The billboard pictured in Bourke-White’s photograph belonged to a campaign implemented by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), an industrial trade and lobby organization. The Depression era witnessed both government and private business interests increasingly turn to public relations to advance their respective agendas. Bourke-White’s photograph is a convergence of these trends. But what about the African Americans pictured?

In the Life image, the blacks pictured appear as black Americans were: among the most impoverished, disenfranchised, and vulnerable in the nation. They unwittingly perform the public relations work of the FSA image as the emotional center of the scene. They are public relations objects. This chapter tells the story of how the crisis in capitalism in the 1930s provided an opening for African Americans to enter the field of public relations. The training they received as New Deal imagemakers and image managers would prove essential to black campaigns to redefine blackness and, in particular, black citizenship.

In 1933, newly elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt initiated the New Deal to “stop the bleeding,” save U.S. capitalism, and aid the nation’s psychic healing. A series of emergency relief, public works, and financial reform programs, the New Deal constituted the largest government relief apparatus in U.S. history. It was also a public relations apparatus larger than any to that point in the nation’s history. The scale of operation of this federal public relations machine required the participation of African Americans, particularly when it came to selling New Deal programs to black America.

Moss Hyles Kendrix is a central black figure in the development of public relations, particularly in relation to the New Deal. A young, southern black man, Kendrix became an official New Deal publicist when hired to represent the National Youth Administration (NYA), an agency that addressed unemployment among American youths between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five. Born on March 8, 1917, he experienced the Great Depression while coming of age in Atlanta, Georgia, a city enveloped by federal employment, education, and public works programs that permeated life across racial lines. His Depression-era experiences highlight connections between Roosevelt’s New Deal, federal conceptions of “America” and American citizenship, contemporary black political concerns, and the development of modern public relations. As a New Deal publicist, Kendrix promoted New Deal programs, as well as ideas about American character, citizenship, and capitalism that legitimated the government’s expansive role. The New Deal had many skeptics and outright opponents, including multiple members of Congress, due to the politics of interventionism and social democracy at its center. Roosevelt’s recovery initiatives required constant selling and reselling, as did the worthiness of the constituencies these programs served—largely recognized as the first generation of modern welfare recipients.

Those who knew Kendrix best swear he was born for public relations. Remembering his father, Moss Kendrix Jr. puts it plainly: public relations was “his avocation as much as his vocation.”2 Contemporaries described the elder Kendrix as a “well-known, well-liked, handsome, intense [and] sophisticated” man who desired to “work with people” and who was indefatigable and relentless by nature.3 He was also a handsome man with a soft face and smooth, caramel-taffy-colored skin, the agelessness of which suggested that, like Oscar Wilde’s fictional character Dorian Gray, he might have an enchanted portrait stowed in his attic that bore his wrinkles for him. Large, doe-like eyes stared out from beneath his thick, dark eyebrows, which were often raised with inspiration or expectation and rarely furrowed in worry. “All I want is one new idea each day,” he liked to say.4 In personality and countenance, Kendrix possessed traits that smoothed the way for him into upper-crust circles, both white and black. One reporter summarized, “[He could] mingle with equal ease in the politic phrase-tossing of an Inaugural Ball or the hail-fellow of a national convention”—which he did.5

At the height of his career in the 1950s and early 1960s, Kendrix enjoyed a reputation as one of the most, if not the most, ambitious, and therefore successful, African American marketing specialists on the Eastern Seaboard. With a client list that included large advertisers such as Coca-Cola and Carnation Foods, he interacted with the elite of white corporate America and counted as friends prominent African Americans across the realms of entertainment, sports, business, and journalism. Given his disposition and inclinations, Kendrix was seemingly well suited to professions of persuasion, but, as he was an African American male born and raised in the Jim Crow South, entry into such professions was hardly inevitable. How did he enter a field that, when he reached adulthood, was still in the making and dominated by white, educated businessmen servicing white corporate clients? The answer lies in the necessity to elicit support for the New Deal, which provided African Americans of a particular cultural class the opportunity to become New Deal publicists. In this role, they received training in persuasion politics and contributed to the professionalization, standardization, and legitimization of modern public relations.

As a black New Deal publicist, Kendrix’s job was to sell the national recovery program to southern blacks, which entailed convincing them to participate in New Deal initiatives and commit to the nation’s economic recovery but also, more importantly, to embrace the principles and institutions of democracy. The target market for this sell was hardly primed. African Americans had come to the nation’s aid not so long ago. During World War I, many heeded the instruction of the intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, who instructed African Americans to join the fight, despite their collective experience as second-class citizens. As editor of the Crisis, Du Bois wrote, “Let us not hesitate. Let us . . . forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens.” German victory, Du Bois reasoned, meant “death to the aspirations of Negroes . . . for equality, freedom and democracy.”6 Over three hundred thousand African Americans answered his call. But when they returned, they experienced a “red summer” of nationwide race riots, during which whites lynched dozens of African Americans.7 “This country of ours,” Du Bois wrote on the other side of the war, “is yet a shameful land.”8 How to appeal to this disenchanted, disenfranchised population?

For one, as a New Dealer, Kendrix promoted the Roosevelt administration’s conceptions of American citizenship, which encouraged hard work, displays of unity, and—somewhat ironically, given the circumstances—faith in capitalism. Officials of the New Deal presented national belonging in terms of individual civic contributions. Kendrix, however, bent these “official” discourses of citizenship to contemporary black political concerns, including self-definition, community development and education, and political representation. The publicity and events he produced encouraged African Americans’ sense of duty as citizens and asserted a black citizenship ethos essential to the nation’s greatness. His Depression-era public relations work illuminates the growing recognition of African Americans’ significance as Americans and intentional efforts on behalf of the federal government to identify their concerns and interests and target them on that basis. The nation’s economic crisis provided opportunities and technologies through which Kendrix and other black New Dealers—African Americans employed to promote or administer New Deal programs—redefined and publicized the national belonging of African Americans.

The popular history of the Great Depression remains a white story, populated mainly by dusty and tired, rural white farmers, like the Joad family of John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize–winning 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath. When schoolchildren in the United States do encounter African Americans in the Depression story, it is often as former slaves, because a popular educational source from the period is firsthand accounts of slavery collected by the Works Progress Administration (WPA)—a New Deal agency—during the Depression. While invaluable (if also problematic) historical sources, WPA slave narratives foreground the inferior social position of blacks within U.S. history. Moreover, these Depression-generated narratives of blacks’ enslaved experiences supplant stories of how African Americans actually experienced the Depression.

When African Americans appear in historical studies of the Depression or New Deal, it is generally in the form of voter-relief recipients (the “poor black masses”), artists, or bureaucrat-reformers—most notably the educated black activists that composed the Federal Council of Negro Affairs, popularly known as Roosevelt’s Black Cabinet.9 Kendrix offers an alternative and understudied example of the New Deal agent. What prompted Kendrix and other African Americans to assist the government in its promotion of American democracy and capitalism, given their collective experience as marginalized citizens? What black political agendas did black participation in the New Deal public relations machine serve? Finally, what does knowledge of black New Deal public relations work add to our understanding of the Depression, t...