![]()

CHAPTER 1

WELCOME TO THE NUDIST COLONY

During the summer of 1939, the Los Angeles newspapers were full of Hollywood gossip and rumors of scandalous sex. In and of itself, such titillation was nothing new, but circulation skyrocketed in July as the story broke that a young female member of a local nudist colony, Fraternity Elysia, had committed suicide after a boozy night of partying. As the papers told it, nineteen-year-old Dawn Hope Noel shot herself at her home in Van Nuys after a raucous weekend at the nudist camp and an argument, off-site, with her thirty-six-year-old musician husband. The fact that she was the daughter of stage and silent film actress, Adele Blood Hope, who had also died a few years earlier of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, further fueled sensational headlines about the nudist “girl wife” for weeks. Though the Los Angeles homicide bureau ruled the unfortunate event a suicide and closed the case within a day, the local press, together with city and county officials, drummed up scenarios in which Fraternity Elysia camp members, and nudism in general, were really the responsible parties.1 Against a backdrop of “life in the gay Bohemianism of a nudist colony,” the Los Angeles Times offered grisly details of the hole blown in Noel’s head, while the competing Hearst paper, the Los Angeles Herald-Express, printed daily stories of “unspeakable orgies” taking place behind the “impenetrable walls” of Fraternity Elysia.2

The tabloid coverage violently brought to light a world of naked living that the city and county of Los Angeles previously had tolerated. Always humming in the background, though, were political concerns that anti-materialist collectives tied to health and the body might threaten the region’s social order. The Noel case, with its media-enhanced taint of teen sex, naked debauchery, guns, and drink offered a unique opportunity for local officials to seize on social nudism as a way to earn headlines as warriors against degeneracy and to ban it from the city. As the story unfolded, however, it proved much harder to tamp down Los Angeles’s free and natural lifestyle than politicians and legislators ever would have believed, while the smear campaign against nudism would successfully keep it out of the county for almost thirty years. One of the many paradoxes of free and natural living as it took shape in the United States was that as much as its proponents may have wanted to be free of media scrutiny, it would be to both print and film that they would turn to produce a more flattering self-image and to fight the conservative authorities who challenged them.

American nudism, and the free and natural lifestyle of which it was a part, grew out of Lebensreform (or “life reform”), a mid-nineteenth-century German health movement that encouraged urban dwellers to address the ills of industrial society by living more naturally. Nudist philosophy, which was referred to by British practitioners as naturism, and by Germans as Nacktkultur, included vegetarianism; exposure to fresh air, water, and sunlight; abstinence from tobacco and alcohol; and back-to-nature activities like gardening, hiking, and camping.3 To explain social nudism to American audiences, and study the therapeutic possibilities of group nudity, Howard C. Warren, a professor of psychology at Princeton, published a widely circulated essay in 1933 in which he described his stay at the German nudist camp, Klingberg, near Hamburg. Klingberg was owned by Paul Zimmerman, who had purchased the property in 1902, in social nudism’s very early years, and had raised his family according to the principles and protocols of the emergent body culture. Warren described the features of nudist etiquette, such as wearing clothes when seated for meals and the underpants worn by menstruating women. He joined the rigorous gymnastic regimens, led by physical education teacher, Herr Luhr, who banged a drum to summon camp-goers to morning calisthenics. Warren explained that “in keeping with the ideal of nature living,” the floors of the rustic cabins were of “pure sand.” He described the diet as strictly vegetarian and the stern camp prohibitions against smoking or drinking alcohol. After eight days at Klingberg, a pleasant visit truncated by an upcoming psychology conference in Copenhagen, Warren concluded that nudists were not “radicals, social rebels, or faddists,” nor would he characterize them as “perverts or neurotics.” Instead, everyone was relaxed, “natural, and unconstrained.” He was especially impressed that by alleviating the anxiety prompted by modern attitudes about the body, what he called the “body taboo,” shame and social awkwardness seemed to be swept away. Warren noted the overwhelming fitness of the guests, observing only “two or three men with obtrusive paunches.” Most of all, he was impressed how group nudity decreased the significance of bodies themselves or specific body parts producing “less sexual excitement, less tendency to flirt, less temptation to ribaldry in a nudist gathering than in a group or pair of fully clothed young people.” As delighted as he was by the experience he wrote up in his essay, “Social Nudism and the Body Taboo,” Warren was skeptical if nudism could spread to Western society at large.4

Frances and Mason Merrill, a young couple from New York, had visited Klingberg two years earlier and also feared that nudism could never take hold in the United States. In their 1931 work, Among the Nudists, the Merrills argued that there would always be strong social, economic, and political pressures opposing progressive body politics, ranging from the Protestant prudery of American social reform movements to the Ku Klux Klan’s xenophobia. Not only would nudists appear inherently indecent, but their cultural practice had foreign origins.5 Trying to take a more optimistic tack, the Merrills also noted that despite American social conservatism, there were “certain factors in American life that might favor the progress of the [nudist] movement. The most obvious is the popularity of sunbathing in recent years. During the past few summers, whether seeking health or merely a fashionable ‘sun tan,’ countless Americans have been toasting themselves.”6 But the widespread popularity of suntans in the 1920s and 1930s was not symptomatic of a broader social movement; rather, the intentional suntan was tightly connected to a consumer economy directed toward a new youth market with money to spend on outdoor activities and ready-made clothing like the swimsuit and the backless sundress. Suntans signified leisure and wealth, not socialism or social experimentation.

Mulling over the naturist legacies of Whitman and Thoreau, the Merrills concluded in their second work, Nudism Comes to America, that the only future a nudist movement really could have in America was one of individual rather than social conviction, practiced in small, atomized groups. The Merrills believe that rather than in the countryside, as in Germany, American nudism would be better suited to cities. In their account of informal naked living in New York City, for example, the Merrills celebrated a set of penthouses where four nudist families arranged with their landlord to have exclusive use of their apartment building’s roof for naked suntanning. The Merrills happily reported that “as a result, if one were permitted to go up there now—almost any time, day or night, in comfortable weather—he would find the children of those four families playing, or the adults sun-bathing or lounging about or working, all wholly free of clothes. Here in fact is a group which, though lacking any formal organization, constitution or bylaws, is a nudist ‘colony’ in a truer sense than any ordinary nudist camp or park could possibly be.”7

Unfortunately, urban nudism would prove more challenging than the Merrills had thought. In 1931, Kurt Barthel, the German immigrant who transplanted social nudism to the United States when he founded the American League for Physical Culture in 1929 in New York, quickly foundered when he tried to organize urban events for his membership. After renting a gymnasium and swimming pool for a nude social gathering, league members found themselves promptly arrested and hustled into police vans under the watchful eye of the female neighbor who had called it in.8 Similar incidents ensued and American nudists began to take refuge in the very countryside naturist theorists had suggested they avoid. In case nudists dared to move back to the city, already driven out by police raids on gymnasia and private homes, charges of indecent exposure, and the humiliating news reports that listed their names and addresses, the legislature in Albany, New York, passed the nation’s first anti-nudism law in 1935.9

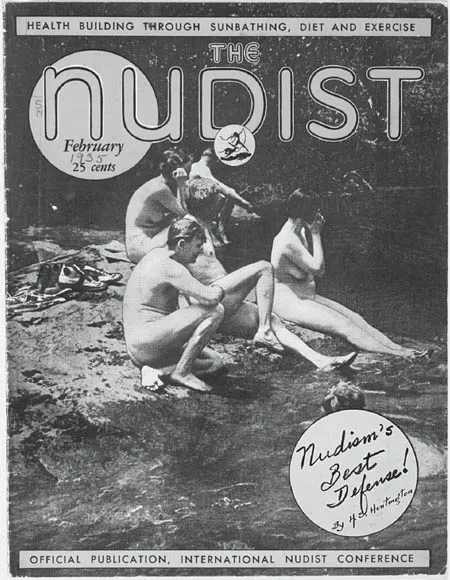

American nudism went on the offensive and in 1931, Kurt Barthel, Ilsley Boone, a Baptist minister, and a mutual friend, David Livingston, laid out the proofs for The Nudist, a short and rather primitive magazine featuring a nude image on its cover and copies of newspaper clippings covering the league’s legal battles with the New York City courts. It clearly made for good reading and The Nudist soon had subscribers in the thousands who enjoyed wholesome, often airbrushed, images of naked sports, nude camping, and other back-to-nature exploits along with lengthy treatises about the importance of the sun for optimal health.10 The original issues of The Nudist often featured mixed-gender groups on their covers, avoiding any suggestion that it might be a girlie magazine, with the bodies crouched or turned in such a way as to cover their genitalia. The implication was that nudism was serious business, with potential for fun, but an activity more akin to labor than leisure. On the cover, for example, a group of nudists have hiked to the lakeshore where they are shown resting after shedding their shoes; this is no simple stroll from their hotel to the beach (Figure 1).

Barthel then expanded the opportunities for free and natural living in April 1932 by purchasing property in Liberty Corner, New Jersey, to establish Sky Farm, the first nudist camp in the country and a member-owned cooperative.11 Shortly thereafter, Boone established his own camp, Sunshine Park, in Mays Landing, New Jersey, which would become the East Coast anchor for organized nudism while his press, the Sunshine Book Company, published The Nudist, establishing it as the movement’s flagship magazine. Together, the camp and the magazine could communicate Boone’s belief “in the essential wholesomeness of the human body and all its functions. We therefore regard the body neither as an object of shame nor as a subject for levity or erotic exploitations.”12 With the creation of the camps, the magazine, and the newly constituted International Nudist Conference (INC), organized nudism took off and inspired the founding of clubs and camps all over country including Ohio, Michigan, California, and New York. By 1933, The Nudist listed forty-four clubs and over three hundred card-carrying members of the INC.13

FIGURE 1. The Nudist 4, no. 2 (February 1935), editor Harry S. Huntington (American, 1882–1981) (New York: Outdoor Publishing). 12 ⅞ × 10 in. (32.7 × 25.4 cm). Wolfsonian-Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida, Gift of Robert J. Young, XC2000.81.33.4. Photo: Lynton Gardiner.

Whatever its portrayal in the popular press, nudism held as its most important tenet that the naked body, once accepted as wholesome and natural, would free Americans from unhealthy obsessions with corporeal perfection and sex. While they would never be able to entirely untether nudity from sexuality, the nudist goal was to live as freely and naturally as modern life would permit believing that the shedding of clothing, with its stark markers of class and gender, would produce a happier, less uptight, and more equitable society. As Boone put it, “The sex significance of nudism lies wholly in the direction of a more wholesome and natural acceptance of men and women on the basis of their total physical, mental, and spiritual selves without making any of these invidious and injurious distinctions which clothes have woven into the fabric of civilization.”14 Though simple in theory, harnessing an overhaul of American social norms to the naked body was far more complicated to execute, starting with the fact that public nudity was illegal and subject to the whims of local law enforcement and the reactions of the clothed.

Built into the free and natural lifestyle in the United States was thus a public-private divide that had as much to do with the evolution of nudism as a philosophy and practice as it did with modern American attitudes about sex, which waffled between the personal freedom to express one’s sexual desires and the impulse to ensure social control through repression and shame. Therefore, American treatises on free and natural living, which often appeared in publications like The Nudist, were very clear that the naked body was a beautiful, natural thing but its reception had everything to do with context. The warning implicit in these writings is that no matter how normal nudists might find nakedness, American society was a long way from catching up. An example from the early 1940s explained that a nudist “does not conceive of the human body as being in anyway shameful in itself ...