![]()

1ORIGINS

Korea, a small country attached to the northeast of China, had been independent for centuries before 1882. From 1882 to 1905 Korea had diplomatic relations with many important nations of the world; the United States signed a treaty of amity and commerce with Korea in 1882. In 1904 Japan requested the cooperation of Korea in its war with Russia. Japan asked permission for its soldiers to pass through the Korean peninsula and made a solemn promise to guarantee Korea’s independence and to withdraw Japanese soldiers after the war was over. Korea, relying upon the word of Japan, allowed the soldiers on its territory, thus contributing to the latter’s victory over Russia. But at the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War, instead of removing its troops as promised, Japan took advantage of the situation and started to take over Korea. The Korean king vigorously opposed Japan’s actions, but since Japan had complete military control of the situation, Korea found itself trapped in a hopeless situation. The king was virtually a prisoner in his palace with no authority to do anything. In 1907 he finally abdicated in favor of his son. This tragedy began a long history of aggression against Korea and created the unhappy world in which the Koreans have lived since 1905.

My paternal grandfather was a teacher, but he also raised mulberry bushes on his property and sold the leaves to a nearby silkworm factory. He owned a stall in the village marketplace that sold dried vegetables, mushrooms, and all kinds of dried seaweeds. Grandfather, being a very wise man as well as a scholar, taught Grandmother to read and write, encouraged her to study his books, and gave her knowledge that was not then available to most women. Grandmother, in turn, taught her daughter-inlaw, my mother, so she had the advantages of a private tutor. Since paper was a scarce item, Mother scratched the letters with a sharp stick on the earthen floor of her kitchen. Mother told me that, unlike most mothers-in-law, hers treated her with love and kindness.

Portrait of the Paik family in Korea, 1905. Left to right, front row: Paik Meung Sun (author’s brother), Paik Kuang Sun (author); middle row: Paik Goon Un (grandfather), Sin Bok Duk (grandmother), Paik Suk Wha (aunt); back row: Paik Sin Chil (uncle), Paik Sin Koo (father), Song Kuang Do (mother), and uncle’s wife (name unknown).

Two of the first American Presbyterian missionaries to come to Korea were Dr. Moffett and Dr. Underwood; Moffett eventually settled in Pyongyang. My father was one of the Koreans who taught him to speak Korean. Dr. Moffett also learned the written language, translated the Bible into Korean, and built churches and hospitals. Our family had all converted to Christianity before I was born. Paik Meung Sun, my older brother, was born on November 1, 1897, and I, Paik Kuang Sun, was born on August 17, 1900. We were both baptized by Dr. Moffett.

Grandmother was so impressed and motivated after studying the Bible that she felt the urge to share it with her friends and neighbors. She spent all of her spare time going from house to house, teaching the women to read and write so they could study the Bible with her. As her circle widened, she obtained a donkey to help her go beyond her village. Then the idea of establishing a girls’ school became her real ambition. She convinced the mothers that their daughters should also be able to enjoy the knowledge that they themselves were acquiring. Due to her strong personality, patience, and perseverance, and to Grandfather’s influence in their community — and in spite of much opposition and criticism from the men — she started the first girls’ school in Pyongyang in a small thatched hut.

Her life story shows that whenever women get together and work for a good cause, miracles can happen. From a most humble beginning, Grandmother saw her dream grow, bit by bit. Eventually the thatched hut became a very large brick building, with hundreds of female students attending. Many years later, I met several women in Los Angeles who had graduated from her school.

Although I do not remember the faces of my paternal grandparents, two experiences remain in my memory. The first is waiting for my grandfather to come home in the late afternoon. He left home early every morning before I was awake to attend to his business in the village marketplace. I always sat on the front steps, impatiently waiting for his return. As soon as he turned the corner a block away, I would run out to meet him. He would pick me up in his arms, laughing and pretending not to know why I was searching his pockets. He always had yut candy and other surprises for me. I can still hear his laughter and jolly voice. I was told many years later that yut candy is made from barley sprouts. It is naturally mildly sweet with no added sugar and is pulled like taffy and cut into small pieces. It was children’s favorite candy in those days.

The second thing I remember is Grandmother strapping me on her back one morning and saying she wanted me to see her girls at school. As we entered the room, I looked over her shoulder and saw a large room full of girls who rose to sing a song, perhaps in greeting to their teacher. Grandmother spoke for several minutes and then dismissed the class. That is my only remembrance of her, though we received a few pictures and many letters from her and my uncle through the years we lived in America.

My uncle was the principal of the Pyongyang high school for many years; he was also a minister. His six daughters grew up to be schoolteachers. My father had also studied for the ministry and was about to be ordained when suddenly we were forced to leave Korea.

My maternal grandparents lived in Yangwu, a village some distance away. I do not remember them at all. Most people at that time traveled on foot only, so with the exception of very urgent matters, faraway relatives did not just drop by for visits. The marriage between my mother and father had been arranged by a paid matchmaker, as was the practice in those days. My mother’s family were poor farmers; perhaps that is why they did not mind her, their only child, moving so far away to marry. Later on, my parents joked that her family had arranged the marriage because Father came from a family of ministers and teachers, so they thought her marrying him would be a step up; little did they realize that as soon as they came to the United States she would have to work on a farm again. Mother was sixteen and Father was twenty-two when they married.

One afternoon in 1905, as I was waiting on the front steps for Grandfather, I saw two men attired in strange-looking clothes walking towards our house. As they stopped at our gate, I ran into the house to call Grandmother. She came out to meet them. After a few minutes she returned, looking very serious, and said that we had to move out right away. This caused much talk and excitement during the evening meal. It turned out that the two strange men were Japanese officers, and they wanted everyone to move out so they could use our home to house their soldiers. As Grandmother told about the Japanese soldiers, my family sat in stunned silence. Although the news was no surprise to them, it must have felt as though the sky had fallen on us. Soon friends came over, asking what should be done. The only choice was to leave that night or to stay and live with the soldiers in our home, which no one wanted to do. I don’t remember any of the details of what happened that night. It was so confusing. In the next few days, every evening as our family ate dinner they talked about all the disturbing rumors from other parts of our country. I felt a bit uneasy, but I was too young to realize the significance of these events and soon forgot about them in play. My family must have made a decision about what to do when the soldiers arrived, but I didn’t know about it until later.

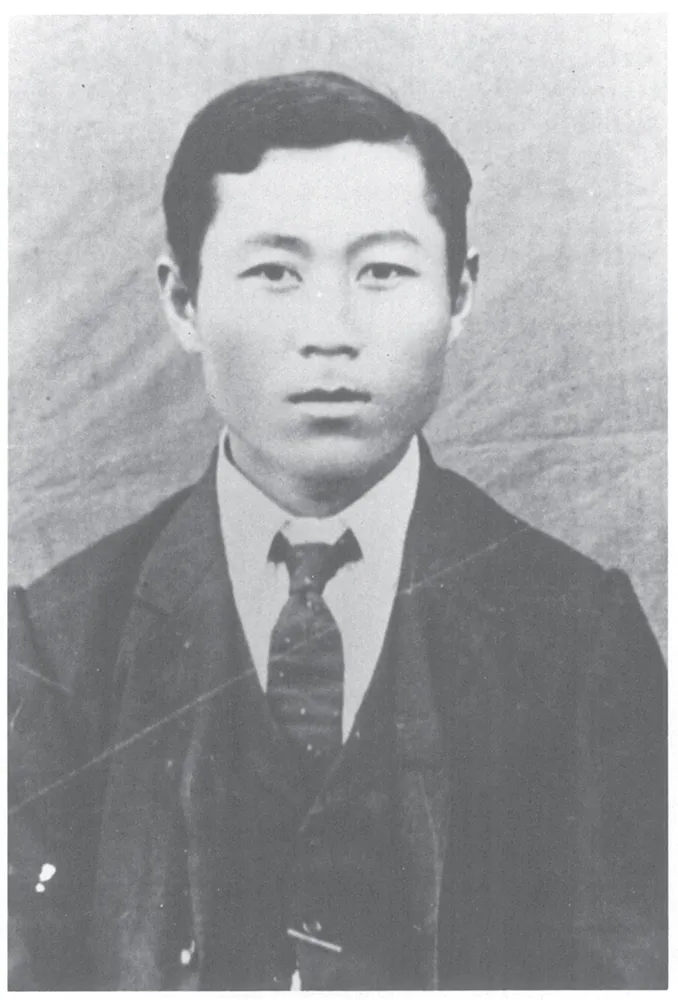

Passport issued to Paik Sin Koo in 1905.

The family decided to go to Inchon, the nearest large city with a harbor, to see what we could do for a living there. It took several days and nights of walking with very little rest to reach our destination. We could only bring our bedding, clothes, and food for the journey. Father must have carried me on his back, but I must have slept most of the way because I don’t remember anything about the trip. Many of our friends and neighbors came with us. Mother said that God must surely have been guiding us in the right direction.

There happened to be two ships in Inchon harbor, sent by owners of sugar cane plantations in Hawaii to recruit workers. People were told that if a man signed a contract to work for one year, he and his family would be given free passage to Hawaii. After that, he would be free to go wherever he wished. His wages were to be fifty cents per day, working from dawn to dusk. Father signed on, and that was how we went to Hawaii on the S. S. Siberia, arriving on May 8, 1905.

Before leaving Korea we had a family picture taken. The hour of parting must have been very sad and tearful, each of them knowing that they would probably never see one another again. Father was thirty-two, Mother was twenty-six, my brother Meung Sun was eight, and I was five when we left Korea. Many of our friends left with us. All I remember about that trip is that Mother never left her berth, and I was also very seasick at first. After a few days, I felt a bit better and managed to find my way up to a deck where Father’s friends walked around. They took turns carrying me on their backs and told me it was dangerous for little girls to be walking on deck alone, because it was easy to get swept off by waves when the ship swayed back and forth. When I said that I had not eaten for several days, they took me down to the galley where a Chinese cook gave me a wonderful-tasting bowl of hot noodles. I felt much better after that and forgot about seasickness.

![]()

2OAHU AND RIVERSIDE

Life in Hawaii was not much different from that in Korea because all the people I came in contact with were Orientals. I don’t remember seeing white people, at least not face to face. There was a small group of Koreans in Oahu, where we lived, and a small church. Father preached there sometimes when he was not working on the plantations. He must have done hoeing or weeding: since he had not had any farming experience, he could not do specialized work such as picking. Mother wanted to work as well, but Father would not allow her to. He said, “Even if we have to starve, I don’t want you working out in the fields.”

When I asked Father years later if we had eaten bananas in Hawaii, he replied that although a big bunch of bananas sold for five cents, he could not afford to buy any. Since we had arrived with only the clothes on our backs and our bedding, we never had enough money left over to buy bananas. We lived in a grass hut, slept on the ground, and had to start from scratch to get every household item. Fortunately, the weather was warm, so we didn’t need much clothing, but we never had enough money for a normal way of life.

While we were living in Hawaii, Mother didn’t have much housework to do in the grass hut, so she had time to talk to us about why we were the only ones in our family to have left Korea. She told me that I had begged Grandmother to come with us, but she wouldn’t leave her school. Grandmother had said that her students were depending on her to teach and guide them. She was certainly a very remarkable woman, with much courage in the face of danger. It is women like her who get things started in spite of opposition, and who accomplish what seem like impossibilities. I’m glad she lived to see her dream come true. She loved all of her students as though they were her own children, and she wouldn’t desert them in their time of need. Uncle said the same thing about the young boys in his high school. Also, he had a wife and several children of his own to care for. Of course, Grandfather would not leave without Grandmother. So only my father had no obligations to anyone except his own wife and two children.

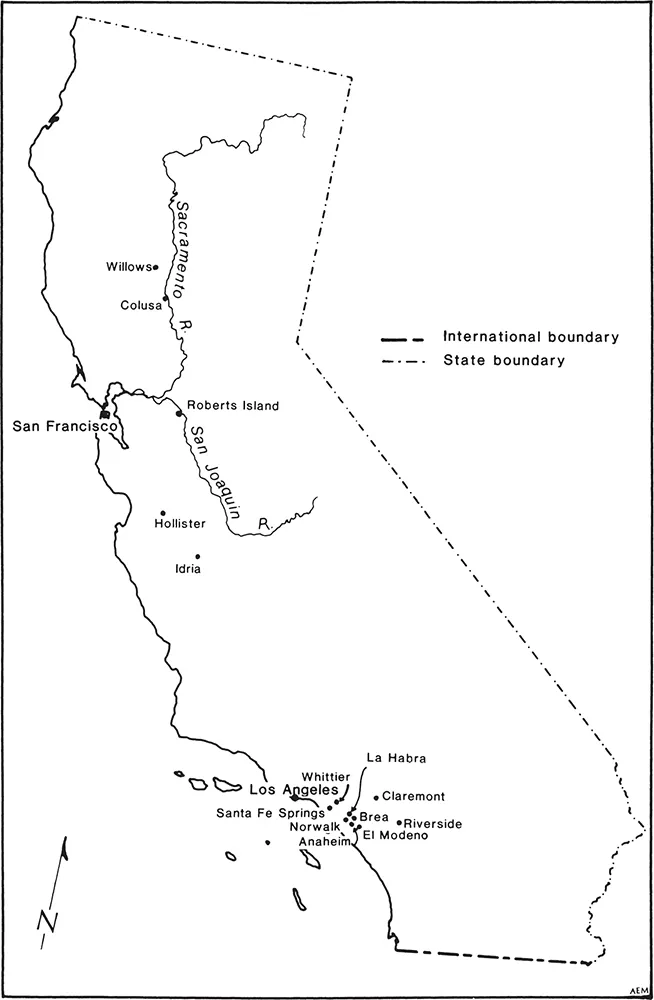

California: locations where Mary Kuang Sun Paik Lee has lived.

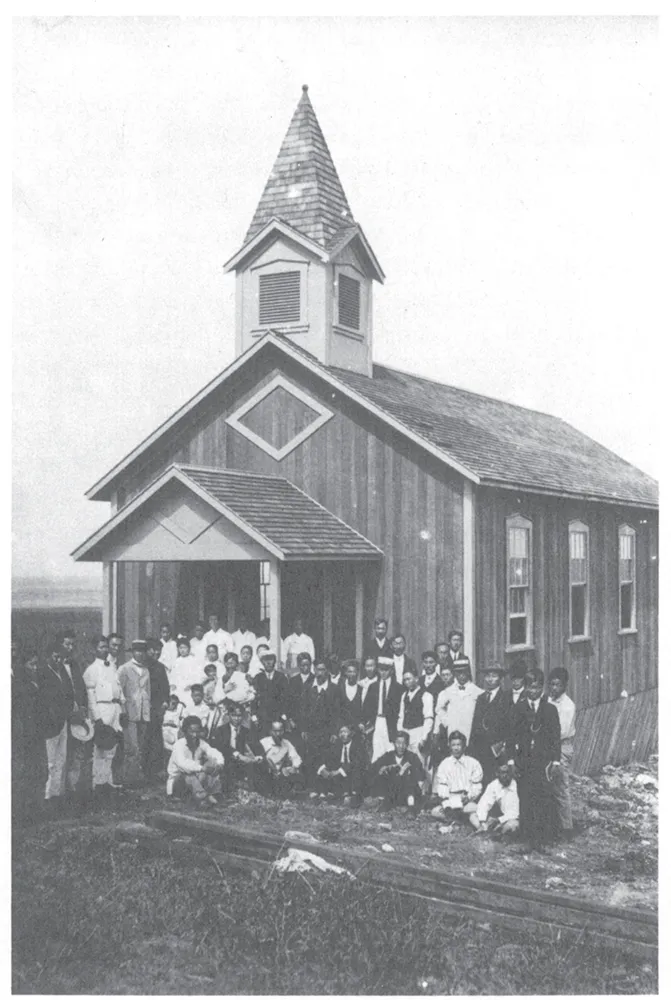

Church on (Ewa?) plantation in Oahu where Korean workers worshipped. Paik Sin Koo is standing, wearing a hat and watch chain, fourth from right.

Mother told me there had been a lot of discussion for several days before the final decision was made for my parents, my brother, and me to leave Korea to find a better life elsewhere. Father was reluctant to leave, but his parents insisted, saying that his presence would not help them. They knew what would happen to them in the near future. They were prepared to face great hardship or worse, but they wanted at least one member of their family to survive and live a better life somewhere else. Such strong, quiet courage in ordinary people in the face of danger is really something to admire and remember always.

My second brother, Paik Daw Sun, was born on October 6, 1905, in Hawaii. Father was desperate, always writing to friends in other places, trying to find a better place to live. Finally, he heard from friends in Riverside, California, who urged him to join them: they said the prospects for the future were better in America; that a man’s wages were ten to fifteen cents an hour for ten hours of work a day. After his year in Hawaii was up, Father borrowed enough money from friends to pay for our passage to America on board the S. S. China.

We landed in San Francisco on December 3, 1906. As we walked down the gangplank, a group of young white men were standing around, waiting to see what kind of creatures were disembarking. We must have been a very queer-looking group. They laughed at us and spit in our faces; one man kicked up Mother’s skirt and called us names we couldn’t understand. Of course, their actions and attitudes left no doubt about their feelings toward us. I was so upset. I asked Father why we had come to a place where we were not wanted. He replied that we deserved what we got because that was the same kind of treatment that Koreans had given to the first American missionaries in Korea: the children had thrown rocks at them, calling them “white devils” because of their blue eyes and yellow or red hair. He explained that anything new and strange causes some fear at first, so ridicule and violence often result. He said the missionaries just lowered their heads and paid no attention to their tormentors. They showed by their action and good works that they were just as good as or even better than those who laughed at them. He said that is exactly what we must try to do here in America — study hard and learn to show Americans that we are just as good as they are. That was my first lesson in living, and I have never forgotten it.

Paik Sin Koo in Hawaii, 1905.

Many old friends came with us from Hawaii. Some stayed in San Francisco, others went to Dinuba, near Fresno, but most headed for Los Angeles. We ourselves went straight to the railroad depot nearby and boarded a train for Riverside, where friends would be waiting for us. It was our first experience on a train. We were excited, but we felt lost in such a huge country. When we reached Riverside, we found friends from our village in Korea waiting to greet us.

In those days, Orientals and others were not allowed to live in town with the white people. The Japanese, Chinese, and Mexicans each had their own little settlement outside of town. My first glimpse of what was to be our camp was rows of one-room shacks, with a few water pumps here and there and little sheds for outhouses. We learned later that the shacks had been constructed for the Chin...