![]()

PART ONE

CITY OF MIGRANTS, 1940–1960

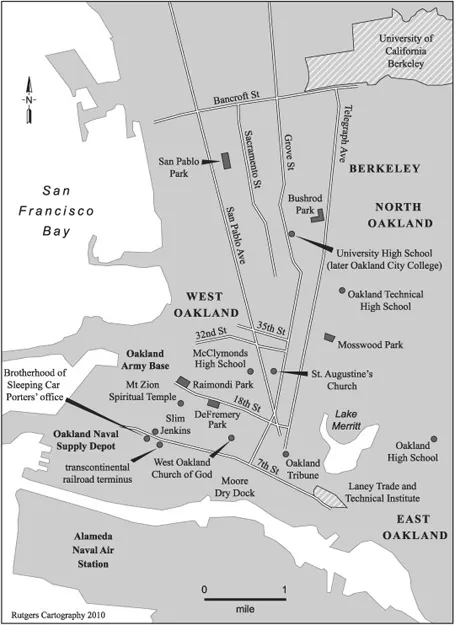

Oakland and Berkeley, 1940–1960

![]()

1. CANAAN BOUND

In 1948, Harry Haywood wrote, “The Negro Question is agrarian in origin. . . . It presents the curious anomaly of a virtual serfdom in the very heart of the most highly industrialized country in the world.”1 World War II and the advent of the mechanical cotton picker resolved this contradiction by spurring the single largest black population movement in U.S. history. In the three decades following the economic collapse of the 1930s, African Americans who had been tethered to the land at near subsistence abandoned their rural moorings by relocating to cities. The 1950 census documented that in the past ten years “more persons moved from rural to urban areas than in any previous decade.”2 In an ever-expanding tide, migrants poured out of the South in pursuit of rising wages and living standards promised by major metropolitan areas. In 1940, 77 percent of the total black population lived in the South with over 49 percent in rural areas; two out of five worked as farmers, sharecroppers or farm laborers. In the next ten years over 1.6 million people migrated north and westward, to be followed by another 1.5 million in the subsequent decade.3 Large-scale proletarianization accompanied this mass urbanization as migrants sought work in defense industries. The rate of socioeconomic change was remarkable. By 1970, more than half of the African American population settled outside the South with over 75 percent residing in cities. In less than a quarter century, urban became synonymous with “black.”4

The repercussions of this internal migration extended throughout the United States leaving their deepest imprint on West Coast cities that historically possessed the smallest black populations. California boasted the largest increase of nineteen western states; a steady influx of newcomers poured into urban centers from San Diego to Marin City. During World War II, lucrative defense jobs made the “Golden State” a prime destination for southern migrants. Sociologist Charles Johnson explained, “To the romantic appeal of the west, has been added the real and actual opportunity for gainful employment, setting in motion a war-time migration of huge proportions.”5 Throughout the Pacific Coast, a syncretic relationship emerged between war industries and black migration; new settlements bloomed on the edges of military installations and defense plants. By 1943, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce declared the Bay Area “the largest shipbuilding center in the world.”6 With a dense ring of war industries surrounding the city, including Richmond's Kaiser shipyards to the north, Moore Dry Dock to the south, and an expansive new army base just east of the Bay Bridge, Oakland's black population mushroomed from 8,462 residents in 1940 (3 percent) to 47,562 in 1950 (12 percent). In less than a decade, the number of black residents increased over 500 percent.7 A pattern of chain migration continued until by 1980 Oakland reached the racial tipping point with a black population of 157,484 (51 percent), over half of the city's total.8 The resulting shift in demography secured its position as the largest black metropolis in northern California, second in the state only to Los Angeles in the numbers of African Americans.

In wartime and after, the East Bay's southern diaspora permeated every aspect of urban life. Industrial development, housing, police community relations, local government, and, especially, education became sites of conflict and contestation with long-standing residents. Scholars have amply documented how black migration provoked white flight; however, this represents only one part of the larger story of urban transformation. The influx of southern migrants profoundly altered the social organization of northern California's African American communities, ultimately laying the groundwork for their political mobilization in subsequent decades. Migrants, initially branded as unwelcome “newcomers,” quickly subsumed the small prewar population into their quest for political access, a higher living standard, and in the case of the fortunate few, upward mobility. While Oakland's small black community fought for greater social and economic access prior to the war, these struggles vastly intensified in its wake. New social cleavages emerged based on the timing of arrival as well as between the groups able to realize the opportunity the San Francisco Bay Area afforded and those excluded from decent jobs, housing, and education.

Federal defense industries and the transformation of southern agriculture spurred the second wave of the Great Migration, resulting in black migrants’ first of many fights for inclusion. While this mid-twentieth-century population exodus shared many similarities with its predecessor, it also had significant differences. One of the most important was the opening up of “a new migration geography” that connected Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas to the Pacific Coast.9 The increased role of the federal government in California's economy laid the foundation for this massive redistribution of population. West Coast cities first assumed their “metropolitan-military” character during the Progressive Era, but in the San Francisco Bay Area the strong link between defense and the local economy did not emerge until the late 1930s.10 By the end of World War II, the federal government had become the largest public employer in the Bay Area, exceeding the number of jobs in California state and local government combined.11 With the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the West Coast branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), black migrants fought for and won access to highly paid wartime employment. In the process, their campaign highlighted the problem of racial discrimination and established key precedents for equal opportunity legislation and federal intervention to protect civil rights. Unfortunately, their victory proved short-lived. Postwar demobilization left Oakland with a sharply reduced industrial base. In sharp contrast to Los Angeles, which became a center for aerospace technology, the Bay Area's liberty ship industry had few peacetime applications. This hastened Oakland's deindustrialization as a steady stream of businesses began to flee to the East Bay's cheaper, more racially homogenous suburbs. By 1964, the federal government officially declared Oakland a “depressed area.”12

Despite this economic retrenchment, waves of migrants displaced by agricultural mechanization continued to pour into the East Bay. Unemployment soared and many found themselves trapped in the familiar cycles of debt and subsistence that they had fled. Historian Gavin Wright has argued that “the oscillation from a decade of ‘pull’ to a decade of ‘push’ had profound effects on every aspect of human relations in the South.”13 In the postwar era, destruction of thousands of sharecroppers’ homes transformed southern landscapes as mechanized “neo-plantations” replaced their faltering predecessors. African American migration took on the desperate quality of flight as people sought refuge in urban areas despite soaring unemployment rates. Chronic poverty was made worse by the frustrated expectations of new arrivals who vested western cities with special promise. Through challenging discrimination, migrants and their children confronted the established racial order. The older generation drew on churches, civil rights organizations, and the unions, while their children invented new forms of political expression forged in California cities. Ultimately, their combined aspiration produced a social movement that forever changed national understandings of the relationship between race and power, poverty and politics.14

THE INITIAL causes of mass exodus could be found first within the South itself. By the close of the Depression, the southern system of agriculture, which had formed the core of black subsistence since Reconstruction, was breaking apart. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration's policies had seriously damaged the system of tenancy through large-scale displacement of landless farmers. Attempts to raise cotton prices through restricting production combined with direct cash grants to owners with little federal oversight led to a sharp reduction in the land allotted for tenancy. Although black and white alike suffered, African Americans with no political recourse under segregation bore the brunt of this policy. While FDR bowed to the social order of the South by refusing to intervene more forcefully—”I know the South, and we've got to be patient”—a quiet economic revolution had been set in motion. Wage labor rapidly replaced tenancy, and agricultural workers’ incomes dropped precipitously as industrial wages rose.15 Death rates among African Americans, which had been steadily declining, suddenly spiked.16 All these factors converged to drive rural populations first into nearby cites, and when employment opportunities opened up during the war, to the distant North and West.17

Wartime defense industries exacerbated the collapse of tenancy by stripping plantations of labor and providing a strong economic incentive for mechanization. The technology for preharvest cultivation had been available in the first decades of the century; however, it was rarely used in the South. It was not until a shortage of labor and an increase in wages ensued that it made economic sense for planters to implement change. In 1936, after Congress passed the Social Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act, which allowed for direct cash payments to tenants, owners’ revenues declined, and they turned increasingly toward wage labor and its counterpart, mechanization.18 Despite depressed conditions, plantation areas purchased large numbers of tractors in the 1930s, at a significantly higher rate than other regions. Tenant evictions accelerated in the second half of the decade, and the floundering southern industrial sector could not absorb the surplus population. According to historian Gavin Wright, “Five southern states had fewer industrial jobs in 1939 than they had in 1909, and the South as a whole enjoyed virtually zero net growth in industrial employment between 1929 and 1939.”19

As employment opportunities opened up in federal defense industries, the mass out-migration of African Americans to northern cities left stretches of commodity agriculture in crisis. The population of farmers, composed primarily of sharecroppers and laborers, dropped by over 3 million people (22 percent) during the war.20 Louisiana's cotton plantation parishes consistently hemorrhaged black population throughout the 1940s at a rate of between 4 and 31 percent. Sugar, grain, and truck subsistence parishes suffered more moderate losses. While many had chosen to relocate to larger parishes (cities of 10,000 or more), which experienced net gains, significant numbers fled the state altogether. In May 1943, a draft notice published in the Madison Journal noted that of the thirty-five black locals called up for selective service, only six remained; nineteen of the total had relocated to California or Nevada. In the resulting vacuum, women, children, and even prisoners of war were called upon to fill the labor shortage.21 Farm wages nearly tripled, and a brief respite followed in the war's aftermath. However, black exodus spiked again in the late forties.

Initially, planters relented by trying to improve conditions at home. In hopes of retaining tenants, southern states responded to long-standing demands for “equalization” and increased funding to segregated schools. For a brief period between 1945 and 1950 this narrowed the racial education gap.22 However, these efforts remained short-lived. In order to secure production, planters ultimately turned to mechanical cotton pickers which quickly made large numbers of sharecroppers and farmworkers extraneous. In the initial phases, the need for wage labor increased between 1945 and 1954. However, in the final stages of mechanization, obsolescence replaced the acute labor shortage almost immediately. By the midfifties, rural to urban migration had become a necessity rather than a choice.23

While people fled from regions throughout the South, and brought with them a diversity of experiences and backgrounds, Bay Area war migrants shared some particular characteristics. The majority came from Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma, with Arkansas and Mississippi supplying lesser numbers.24 A slightly larger percentage of women had chosen to emigrate, and in the 19–24 age range, they outnumbered men by a ratio of two to one. The lure of lucrative defense jobs and the chance to abandon domestic work most certainly played a role. In the words of one female shipyard worker, “It took Hitler to get us out of the kitchens.”25 As a whole, the “newcomers” were significantly younger than the resident black population; the average age of men was 23.3 years, and of women, 22.9 years.26

In postwar Oakland, Louisiana held pride of place and exerted a constant influence on local politics and culture. Of the five states that East Bay migrants hailed from, Louisiana had the second largest black population, totaling 37 percent in 1930. It shared a number of similarities with its eastern counterpart, Mississippi, including the rapid disfranchisement of African Americans in Reconstruction's aftermath and an entrenched system of separate and unequal schooling resulting in comparable illiteracy rates. However, there were also significant differences that became manifest in the transplanted African American community of the East Bay. Much larger percentages of Louisiana's black population lived in urban areas, and they had one of the highest rates of occupational mobility in the South. This resulted in significant numbers of black skilled and semi-skilled craftsmen who had a strong tradition of labor activism with roots stretching back to several unions and benevolent associations in the late nineteenth century. In New Orleans, for example, the building and transportation trades were completely dependent on African American skilled labor, with blacks constituting 28 percent of all carpenters and joiners, “62 percent of all coopers, 65 percent of all masons,” and “75 percent of all longshoremen.”27 In sum, of the five states in question, Louisiana had the largest black professional class and the highest rates of income and property valuation. While suffering brutal segregation, black New Orleans possessed a strong infrastructure of businesses, universities, churches, and social organizations that made it possible to retreat from the hostile world of the white majority.28

The social profiles of wartime migrants refuted common stereotypes applied to them as a group. The secondary urban migration during the war served as an important contrast to the waves of newcomers that followed, who were composed largely of people displaced from rural areas.29 Charles Johnson's extensive study, The Negro War Worker, revealed the image of the uncouth, if harmless, naïf set adrift in the industrial city as urban myth. In general, migrants were comparably educated to their California peers with little disparity, especially at the upper end. The average newcomers completed 8.64 years of schooling, and while larger numbers were concentrated...