![]()

1

‘We Put All Our Hope in Him’: Ephraim Moses Lilien and His Oeuvre

He experienced Zionism on his own body, internalised it completely. Precisely because he belongs to the young generation, he is one of us … His book Juda and his Hebrew ex libris earned our full admiration, and we put all of our hope in him.

— Martin Buber, ‘Address on Jewish Art’

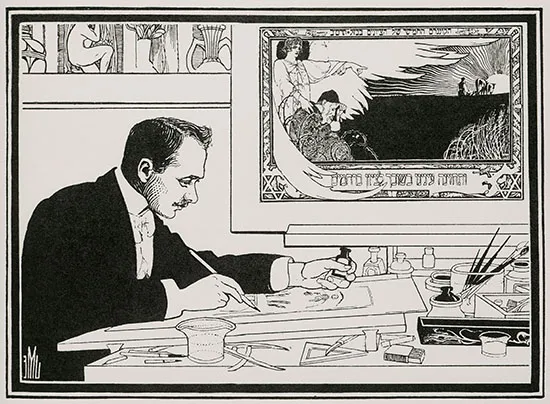

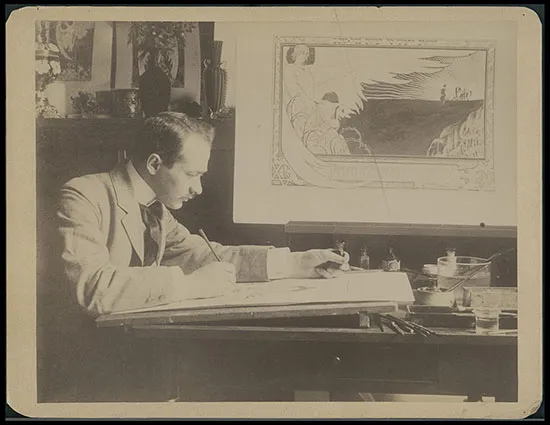

In 1912, at the height of his fame, thirty-eight-year-old Ephraim Moses Lilien drew a black and white self-portrait in which he depicted himself in full evening dress absorbed in his work at his drawing table. The self-portrait was probably based on a photograph taken in 1902. To emphasise the importance of his work as an artist, his hands, holding an ink bottle and pen, are at the centre of the composition. The other tools of his trade – a compass, brushes, drawing utensils, empty water containers – lie scattered around his work surface. Resting on an easel behind him is his most recognised artwork, the Congresskarte (Congress Card), which he created for the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901 (2.6). A little more than a decade later, the Galician-born Lilien portrayed himself as a respectable and well-off professional, the epitome of the cultured German Bürger (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2).1

Figure 1.1 E. M. Lilien, Selbsportrait (Self-Portrait) with Vom Ghetto nach Zion in background, 1912. Oz Almog, Gerhard Milchram, and Erwin A. Schmidl, E. M. Lilien, Jugendstil, Erotik, Zionismus [eine Ausstellung des Jüdischen Museums der Stadt Wien, 21 Oktober, 1998 bis 10 Jäner, 1999 und des Braunschweigischen Landesmuseums, 21 März bis 23 Mai,1999] (Vienna: Mandelbaum, 1998), 21. Photograph by I. Simon. Courtesy of the Braunschweig Landesmuseums.

Figure 1.2 Photograph of Ephraim Moses Lilien at his desk, 1902. Probably from the German Jewish Press. From the Schwadron Portrait Collection. No. 002780928. Courtesy of the National Library, Jerusalem.

At the time Lilien drew this self-portrait, he was the most important and prolific artist of the Jewish national art movement. Martin Buber, the movement’s central figure and guiding light, had pronounced Lilien’s illustrations the ‘hope’ of the entire fledgling movement for how perfectly they reflected the Jewish regeneration in the visual as well as the literary arts.2 His bold black-and-white graphic Jugendstil drawings and etchings feature ornamental borders filled with swirling plant and flower motifs and images of naked women influenced by the work of Aubrey Beardsley and Gustav Klimt.3

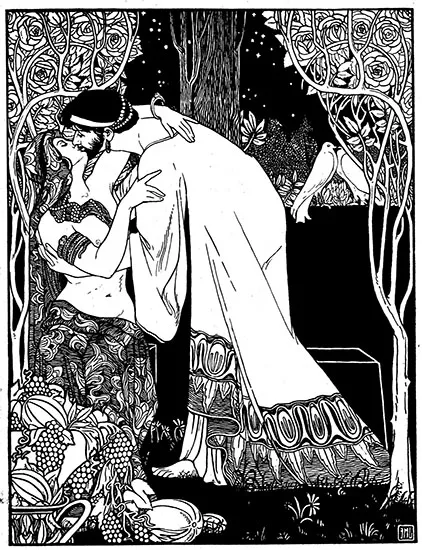

The German Jewish public first became enamoured with Lilien for his series of illustrations that appeared under the title Juda published around 1900.4 The illustrations revealed a distinctly nationalist vision of a modern Jewish utopia outside fin-de-siècle Germany. By 1914 and after the publication of two more books, Lieder des Ghetto (Songs of the Ghetto, 1903) and three volumes of the Die Bücher der Bibel (The Books of the Bible, 1908–1912), Lilien’s fame as an accomplished artist was complete (Fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.3 E. M. Lilien, Das Stille Lied (The Silent Song), Juda, c. 1900. In Börries von Münchhausen, Juda, Gesänge Von Börries Freiherrn V. Münchhausen Mit Buchschmuck Von E. M. Lilien (Berlin: Egon Fleischel and Co., n.d.), n.p.

***

Lilien’s oeuvre encompasses photographs, drawings, illustrations, bookplates, and etchings. This book focuses on the artist’s images of the Jewish male and female heroes that appeared in Juda, Lieder des Ghetto, and Die Bücher der Bibel.5 Lilien drew his inspiration for them from two major sources: the Holy Land, known during the nineteenth century as the ‘cradle of civilisation’, and the Hebrew Bible, where the literary narrative of the ancient Jewish people unfolded.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, increasing numbers of Europeans began travelling to the Middle East on a quest to identify the locations and authenticate the narratives of the Bible, the sacred religious text for both Christians and Jews.6 Many documented their accounts, particularly the British and French, who toured the region in increasing numbers from the 1830s onwards.7 The fields of archaeology and religion eventually joined forces in an effort to confirm the truth of the biblical narratives. In 1865, a group of British churchmen and Christian biblical scholars established the first exploration fund dedicated to the material past of the Levant. The British initiative led to similar ones from Germany, France, and America.8 In addition to being scientific missions, these expeditions promoted the self-interest, political ambitions, and colonial conquest of their respective national sponsors.

The development of Jewish nationalism paralleled the growing interest in orientalist scholarship and archaeology that emerged in Germany during the late nineteenth century.

Lilien, who made his first visit to the Holy Land in 1906, was so inspired by its distinctive geography and people that his illustrations began to focus on these two features: the landscape and its inhabitants. This chapter considers Lilien’s oeuvre in the context of the post-Holocaust study of German history and German art, where Jewish history and art history take into account the German Jewish interest in the East, the Orient, and orientalism. Recent scholarship on the intersection of German Jewish studies and gender, antisemitism, and colonial history suggests that a re-examination of Lilien’s interest in the entangled histories of the Jewish oriental past and their fin-de-siècle occidental experience deserve further study.9

Lilien’s images in historical context

On 29 October 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm II, in a long gold-threaded veil attached to his spiked imperial army helmet, rode on a white stallion into Jerusalem, a city sacred to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, accompanied by dozens of Prussian and Turkish cavalrymen.10 The Illustrated London News and Chicago Daily Tribune reported that he and Kaiserin Augusta Victoria visited the holy shrines and ancient sites of the city, presented a plot of ground to the German Catholics for the erection of a new church, and visited the Protestant church near the Holy Sepulchre.11

In the Kaiser’s race for imperial power, the Bible and the new science of archaeology provided two useful avenues to strengthen German prestige, national identity, and political ambition.12 The Levant held material remains of the past that could be acquired for Berlin’s newest museum, the Pergamon, originally established to house artefacts from Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations in Anatolia in the 1870s, itself a monument to Germany’s rising national power.13 Germany’s drive for colonial conquest in the Near East came as a shock to the British and the French, who had also been cultivating their own spheres of influence in the region at the same time.14 Further heightening fears that Germany might be attempting to establish a protectorate over the Holy Land was the fact that the Kaiser’s visit to Jerusalem was preceded by a stop in Constantinople, where he met with the Ottoman sultan Abdul-Hamid II.15

Theodor Herzl and his Zionist colleagues closely followed Wilhelm II’s colonial pursuit for antiquities, prestige, and regional expansion, hoping for an opportunity to discuss their role in any newfound German foothold in the Near East.16 Since the publication of Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) in 1896, the Zionist leadership under Herzl was aware that it would need the help of imperial powers in order to achieve its goal of securing a homeland for the Jews in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire. For its part, the new Jewish movement might help strengthen European civilisation in the region. According to Herzl, ‘If his majesty the Sultan were to give up Palestine, we could, in return, undertake to regulate the whole finances of Turkey. We should form there part of a wall of defence for Europe in Asia, an outpost of civilisation against barbarism’.17 The Zionist newspaper Die Welt commented on Herzl’s meeting with the Kaiser in Constantinople before he sailed for Jerusalem that, a ‘Germany in the East would bring a new flowering to the people of ancient Palestine’.18 Herzl’s use of the civilising rhetoric of European colonialism and the universal, humane, and cosmopolitan ideals of German Bildung (the cultivation of education, high morals, and ethics) in contrast to the apparently ‘barbaric’ forces in the East reflected the often contradictory and fraught position of contemporary German-speaking Jewry.19 Finding themselves between the perceived influences of the West (secularism, assimilation, and cosmopolitanism) and the confluences of the East (religious identification, Jewish particularity, and apparent lack of culture), Jewish nationalists like Herzl claimed that all Jews should at least be able to live ‘as free men on our own soil and die peacefully in our own homes’.20

Herzl’s desire to meld Western Enlightenment tradition with the ancient history of the Jewish people in the East echoed many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European Jewish biblical scholars’ engagements with the Orient. An array of Central European Jewish academics, journalists, artists, novelists, and poets shared a similar fascination with the East.21 This relationship between the East and West in the German Jewish imagination also informed his images of women, which remained the focal point for much of Lilien’s Jewish oeuvre.22

Contested issues

Problems of German history and art history

Post-Second World War German historians and art historians have had a problematic relationship with the study of German history and German art, not least because both disciplines have had to come to terms with the cataclysmic past of twentieth-century Germany.23 Art historians such as Hans Belting adopted the Sonderweg (special path) theory of German history, which was intent on tracing the origins of Nazi ideology to Germany’s social, political, and intellectually conservative institutions and mentalité in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.24 For Belting, the complex problems of Germany’s art history were traceable to its divided heritage in the political events of the Reformation, where clear divisions emerged between Catholic and Protestant artists. He asserted that feelings of inadequacy next to the supposed more significant artistic traditions of Italy and France had lasting consequences for German art.25 For instance, Albrecht Dürer’s attraction to Venetian painting and Max Liebermann’s for the French Impressionists had called into question these artists’ Germanic status.26 Their art hence acquired an internationalist aspect in contradistinction to German nationalist art.

Following in the footsteps of Belting, other art historians such as Françoise Forster-Hahn ackno...