![]()

CHAPTER 1

DESIGN MATTERS FOR PUBLIC MANAGERS

On November 11th 2008, the British media carried harrowing reports of the brutal death of a 17 month old boy, subsequently referred to as ‘Baby Peter’, in the London Borough of Haringey. Baby Peter’s plight had come to public attention at the conclusion of the trial of his mother, her boyfriend and a family lodger, all convicted of causing his death. The case was seen as a catastrophic failure of the child protection system and Government reaction to public outrage was swift and dramatic. The sense of ‘systemic failure’ (rather than ‘isolated incident’) was reinforced by two disquieting features. First, Baby Peter was not an unknown child, dying outwith the protective bourn of the State; far from it, he had been seen by numerous professionals during his short life and was indeed on Haringey’s Child Protection Register. Secondly, Haringey’s Children’s Services department had, within weeks of the child’s actual death, been given a glowing report by a government inspection1, with praise heaped egregiously upon the department’s Director. Within days, Ed Balls (Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families) ordered an emergency inspection of Haringey, arranged for the Director to be summarily sacked, and instigated a national review of child protection, to be led by Lord Laming. The latter had chaired a prior enquiry into another tragic child death, that of Victoria Climbié, which had ushered in a slew of structural reforms, all designed to keep children safer (Laming, 2003). How, therefore, could it have happened again? A further development was the setting up (January 2009) of the Social Work Task Force to conduct a ‘nuts and bolts’ review of the social work profession and to devise a comprehensive reform programme.

A system in crisis indeed. At this point, I will focus on the part played by a national computer system in these seismic events, the Integrated Children’s System (ICS). Calling the ICS a ‘computer system’ is something of a misnomer; it was much more than that. It represented an attempt to redesign the entire statutory child welfare system in the UK, using Information Technology to achieve this transformation2. Embodying a highly prescriptive framework specifying the precise procedural steps to be followed in handling cases, the ICS attempted to operationalise the Laming reforms in software. Standardisation and the micromanagement of process were seen as the key to quality, safety and the elimination of risk. Although the ICS had been much lauded by Government and senior managers, evidence was coming to light that it was undermining safe professional practice and paradoxically augmenting risk. Research by myself and colleagues had directly implicated it in the death of Baby Peter3 and there were also press reports at the time highlighting the mayhem it was causing:

UNISON4 wishes to draw attention to the seriousness of the problems with the Integrated Children’s System. The problems appear to be fundamental, widespread and consistent enough to call into question whether the ICS is fit for purpose. …we have reports of a number of industrial disputes or collective grievances brewing… and in many more cases staff are voting with their feet and not using the system when they can get away with it (Unison, 2008, pp.8-9).

The miscarriage of the ICS was symptomatic of the failure of the wider system of which it was an essential and integral component. Ultimately the Social Work Task Force called for fundamental review of its design in its final report in 2009 (Gibb, 2009). In this opening chapter, I shall analyse the vicissitudes of the ICS at some length, drawing out key lessons which bear on the central argument of this book, namely that ‘systems design’ needs to be (re)instated as the primary task of the manager. The ICS debacle provides a cautionary tale of design at its worst, both in terms of product and process, and of the dire consequences which ensue when managers abdicate their role as designers. Linked with design is another important trend in contemporary management education, that of evidence-based practice, which I shall weave into the fabric of my argument. The gap between management research and practice is much lamented, at least by those who are aware of it. The goal of management research, like research in any applied discipline, is surely to produce useful theory. But useful for what? For design, of course.

Paradise lost: tales from the trenches

Systems thinking is very much in vogue, in the public services especially (Seddon, 2008). The term embraces a gallimaufry of specific meanings, methods and affiliated sects, as we shall see. Striving for a holistic understanding of the complex causal dynamics of social organisations is its primary goal. When a specific accident or a malfunction arises, it is natural for the systems thinker to see this as a dysfunction of the system as a whole, rather than seeking to blame individuals. Child deaths, such as that of Baby Peter, are therefore construed as symptoms of defective systems design. And if the design is defective, the systems thinker will naturally ask how that system took the form it did, in other words, how was it designed? A maxim is in order: ‘When a system fails or malfunctions, critically interrogate how it was designed’!

In this and the following section, I will attempt to show, from a systemic point of view, just how the ICS had produced the opposite outcome from the one its originators had looked for. My account is based on the findings of a 2 year research study5, which exposed the pernicious impact of the ICS on front-line practice. Let us begin by noting that the ICS does not refer to a particular computer system or software package. Rather it is a national specification, comprising a workflow model, which rigidly defines the social work ‘business process’ in terms of a branching sequence of tasks and timescales, and a reference set of electronic forms, called the ‘exemplars’. Against this specification, software suppliers had been invited to develop “compliant” software implementations (Cleaver et al., 2008), and a number of ICS software products had been produced by several vendors. Although, there were inevitably some variations in quality and usability, the centrally prescribed strictures meant that the ICS had, in effect, been implemented as a national system.

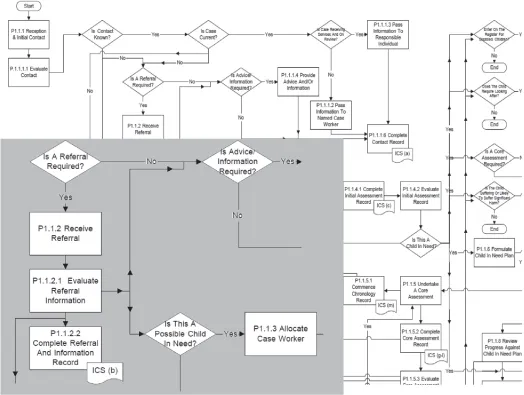

The workflow model of the ICS is shown in Figure 1. It is not meant to be read in detail; rather it is used impressionistically to show how far the zeal for formal modelling has gone. The ‘wiring diagram’ charts the progress of a case from the initial contact, through initial and subsequent in-depth assessment phases. The shaded insert (which overlays some of the diagram) is a blow-up of the early stages of the process. The key decision here is whether to accept the contact as a referral, in which case a full initial assessment must be performed, or that advice/information alone will suffice. Each of the tasks in the model have to be carried out according the sequence given, and there can be no short cuts, no improvisation. For important phases, time-scales are prescribed, which are linked to key performance indicators. All referrals must be responded to within 24 hours and initial assessments must be completed within 7 working days, including a home visit, irrespective of contingencies. When an in-depth, core assessment is needed, this must be completed within 35 days.

Despite its lofty ambitions, evidence that the ICS’s actual impact on practice had been highly disruptive was all too readily found in our research. A universal complaint related to the time taken to record cases electronically: social workers reported spending between 60% and 80% of their available time at the screen, filling in the “exemplars”. Anything but exemplary, these were described as unwieldy, repetitive and difficult to complete and to read. Their lack of practical utility was even more apparent with respect to service users. The following two quotations from social workers illustrate these points:

It is the way they have designed the forms forcing you to repeat yourself over and over again…

The worst is, parents can’t understand them. They are broken into domains and dimensions… Repetitive, loads of boxes. I have to apologise to parents.

The ICS also required that a form be completed for each individual child. For families with multiple children, this naturally invited staff, working under the exacting time pressures imposed by the system, to cut and paste data across forms. This, of course, completely negated the purpose of individual assessment and consumed excessive amounts of professional time. It was also inherently unsafe as such “cloned” information was inevitably not checked properly. The overall effect of such intensified bureaucracy had been to reduce the social work assessment task to data entry, curtailing time for visiting and thinking about the professional casework required to meet the needs of the child. Another general problem was ICS’s emphasis on structured data at the expense of narrative. Practitioners reported that it was difficult to produce “a decent social history” of the family and to make sense of cases from the fragmented documentation in order to obtain a complete picture of the child. A social worker commented as follows:

The government want us to improve our game, get to know each individual child better – but it’s an absolutely impossible task… to get a feel for what’s going on with the child – it’s all chopped up, a complete nightmare – impossible to find the story.

Figure 1: The referral and assessment process as officially “flowcharted”

The problem of the forms was compounded by the tortuous and inflexible workflow model; all steps had to be followed, with a form completed at each stage, however perfunctory. The electronic audit trail was allimportant, as a social worker observed:

It’s much worse since ICS. Like when you’ve got a child in need and you need a conference, you can’t get to the conference without going through strategy discussion and ‘outcome of section 47’ forms. You used to just be able to write like half a side, but now you’ve got these terrible forms.

The pernicious influence of the timescales and targets was ubiquitous. ICS imposes these, providing little scope for workers to exercise intelligent discretion. Worries about timescales for initial (7 days) and core assessments (35 days) had come to dominate practitioners’ worlds. Although workers still managed some artful ‘workarounds’, they also described a strong sense of ‘the system’ now driving practice. As the space for professional judgments had been increasingly squeezed, key professional activities, such as assessment, had become meaningless and mechanistic. Taking short-cuts to meet targets was inevitably undermining good practice, creating what we came to call ‘latent conditions for error’:

If it’s not looking that serious… sometimes you don’t get all the information and the temptation is then to take a short-cut and maybe not contact the school, or because the school are on holidays you say I think I’ve got sufficient information to make a decision- no further action.

The strange history of the ICS: a cautionary tale

Having given a whiff of the dysfunctions of the ICS, let us now delve into the history of its design. Although its origins are a long way off and a little difficult to descry, they may be traced back to the Quality Protects Programme, inaugurated in 1998 by the Department of Health. To ensure that social services were being “delivered according to requirements and are meeting local and national objectives”, this programme prioritised the improvement of “assessment, care planning and record keeping” (Department of Health, 1998, pp.5-6). The centrality of targets and timescales became evident in the subsequent publication of the “Government’s Objectives for Social Services” which set out a range of policy objectives (Department of Health, 1999, p.22). Objective 7 is notable: “To ensure that referral and assessment processes discriminate effectively between different types and levels of need and produce a timely service response”. In its subobjectives, we see the first mention of the time-scales that were subsequently embedded in the ICS: “To complete an initial assessment and put in place case objectives, within a maximum of 7 working days of referral.” The first explicit mention of the Integrated Children’s System appeared the following year, in “Learning the lessons” (Department of Health, 2000a).

The ICS project was subsequently launched, heralded by a briefing paper in 2000. This is notable for its dogmatic certainty that policy aims will be achieved: the ICS is described as “an assessment planning intervention and reviewing model for all children in need… to ensure that assessment, planning and decision-making leads to good outcomes for children” (Department of Health, 2000b, p.1). A steering group for the project was set up (Department of Health, 2002). Its composition is important in the present context: 38 members are listed of whom 23 are civil servants (including the Chair), or directly linked to the civil service. There are three medical experts and four academics. The only direct link with social work practice was via one assistant director of social services and one senior manager.

Thereafter, the ICS evolved over a number of years. Although it originated in the Department of Health, it subsequently came under the wing of the Department for Children, School and Families (DCSF). Throughout its development, design was apparently driven by a small group of senior academics and civil servants, who showed conspicuous resistance to criticism from a very early point (White, Wastell, Broadhurst & Hall, 2010). Adherence to the centrally defined specification was enforced throughout via the publication of increasingly prescriptive ‘compliance criteria’ elaborated in lengthy documents. Although there was an espoused emphasis on piloting and user involvement (Cleaver, et al., 2008), in reality the design had been highly centralised and only...