![]()

1

WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT

“Reading without reflecting is like eating without digesting.”

Attributed to Edmund Burke, 1729–1797

The purposes of this chapter are:

• to introduce the concept of Mental Models as representations of text,

• to introduce the Simple View of Reading and the distinction between word reading and language comprehension,

• to explain the relation between word reading and reading comprehension,

• to distinguish between poor word readers and poor comprehenders.

The click of comprehension

Reading comprehension is important, not just for understanding text, but for broader learning, success in education, and employment. It is even important for our social lives, because of email, text, and social networking sites. Reading comprehension is a complex task, which requires the orchestration of many different cognitive skills and abilities.

Of course, reading comprehension is necessarily dependent on at least adequate word reading: readers cannot understand a whole text if they cannot identify (decode) the words in that text. Likewise, good reading comprehension will depend on good language understanding more generally. This requires comprehension of the individual words and the sentences that they form. However, comprehension typically requires the comprehender to integrate the sense of these words and sentences into a meaningful whole. To do so, construction of a suitable mental model is necessary. A mental model is a mental representation that is created from information in the real, or an imagined, world – i.e. a gist representation of what the comprehender has read (or heard, or seen). It might, but does not necessarily, include imagery. Try Activity 1.1 to get an idea of how important it is to be able to construct a coherent mental model to make sense of the words and sentences of the text.

You might have guessed what the text in Activity 1.1 is about, but if you are like most of the participants in Smith and Swinney’s study (1992), you found it hard to make sense of. Now read the text again, but with the title “Building a snowman”. Now you will find that the obscure references, to e.g. substance, and turns of phrase elaborateness of the final product, suddenly fall into place, and the whole makes perfect sense when you have the appropriate framework for a mental model. Smith and Swinney (building on much earlier work by Bransford & Johnson, 1972) showed that people who were asked to read the above text without a title took considerably longer to read it, and had worse recall of its content, than those who were given the title and were able to use the framework it provided to create an appropriate mental model.

Activity 1.1 The need for a mental model for understanding a text

Read the following short text and try to make sense of it:

This process is as easy as it is enjoyable. This process can take anywhere from about one hour to all day. The length of time depends on the elaborateness of the final product. Only one substance is necessary for this process. However, the substance must be quite abundant and of suitable consistency. The substance is best used when it is fresh, as its lifespan can vary. Its lifespan varies depending on where the substance is located. If one waits too long before using it, the substance may disappear. This process is such that almost anyone can do it. The easiest method is to compress the substance into a denser mass than it had in its original state. This process gives a previously amorphous substance some structure. Other substances can be introduced near the end of the process to add to the complexity of the final product. These substances are not necessary. However, many people find that they add to the desired effect. At the end of the process, the substance is usually in a pleasing form.

The example illustrates two important points. First, it is very difficult to understand a text without an appropriate mental model. This model may draw not only on titles but also on pictures or, very often, on general knowledge. When information in the text is successfully integrated into a mental model, comprehension “clicks”. Perhaps you experienced this “click of comprehension” when you had the title and re-read the text?

The second point is that reading a title or seeing a picture of the situation after you have read the text may help only a little. But if you had seen the title before the text, it would have made the text substantially more comprehensible. The point is that a framework for the construction of an appropriate mental representation makes the text much easier to understand, to reflect about, and to remember.

The Simple View of Reading

It is helpful to distinguish between two main components in reading: word decoding and language comprehension. Word reading (or decoding) refers to the ability to read single words out of context. Language comprehension refers to our ability to understand words, sentences, and text. These are the two key components in The Simple View of Reading (originally proposed by Gough & Tunmer, 1986).

The point of The Simple View of Reading is that variation in reading ability can be captured (simply) in only two components: word reading (decoding) and language comprehension. The name, The Simple View of Reading, is not intended to imply that reading (or learning to read) is a simple process but, rather, that it is a simple way of conceptualising the complexity of reading.

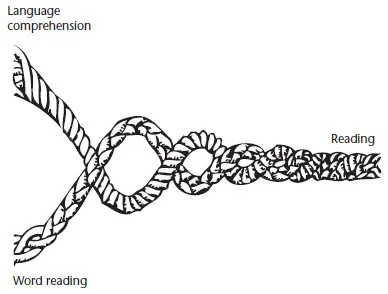

FIGURE 1.1 Skilled reading depends on abilities with both word reading and language comprehension (adapted from Scarborough, 2001).

More precisely, reading ability depends on the product of the two components: Reading = Word Reading × Language Comprehension (R = WR × LC), not just on the sum of the two. This means that if one of the components (either word reading or language comprehension) is zero, overall reading ability will be zero. Thus, if a child cannot read any words or if a child does not have any language comprehension skills, s/he cannot read.

An illustration of the necessity of both components – word reading skills and language comprehension – comes from a story about John Milton’s strategy for reading Greek texts after he became blind. Milton got his daughters to learn to decode the ancient Greek alphabet. They were then able to read aloud the texts in ancient Greek to their father, but they could not understand them, because they did not have any knowledge of Greek, whereas Milton could understand, but not decode, the words. Thus, the daughters provided the word reading skills, and Milton provided the language comprehension skills.

The Simple View on development

Although word reading and language comprehension are largely separate skills, it should always be kept in mind that successful reading demands the interplay of both of these skills, and so they both need to be encouraged and supported from the onset of reading instruction. However, the two skills contribute differently to overall reading as the child develops. For the beginning reader, decoding is new, and children differ hugely in decoding ability. Language comprehension, on the other hand, is quite well developed, especially considering the undemanding books that beginning readers are typically presented with. So in beginning readers, the variation in reading ability is almost identical to the variation in word reading.

In the early school years, children need to establish fluent and automatic word reading, which, although not sufficient for good reading overall, is obviously necessary. However, for most children, this is a time-limited task: the child needs to reach the level of competence at which word reading becomes a “self-teaching mechanism” (Share, 1995) (see Box 1.1). The ability to comprehend texts (including the ability to appreciate texts in different content areas and genres), however, is a skill that will continue to develop throughout adult life.

The language comprehension that provides the foundation for reading comprehension develops before children have any formal reading instruction. When they come to school, children are already very competent comprehenders and producers of spoken language without having had formal instruction in these skills (see Box 1.1). Thus, when children become competent at decoding, it is their competence in language comprehension that will determine their overall reading ability. So in more advanced reading, good language comprehension will be more crucial than word recognition.

Box 1.1 The importance of being taught to decode words

Unfortunately, learning to read words does not usually come naturally to children, in contrast to learning to speak. Humans have used speech to communicate for tens of thousands of years, but reading is, in the historical context, a relatively new skill and it is only in the last hundred years or so that the majority of people in Western societies have been able to read and write. Thus there is no reason to expect that the ability to read would have evolved and have innate roots as the ability to speak is generally assumed to (e.g. Pinker, 1994). Indeed, in many cultures still, the ability to read is the exception, rather than the norm. Learning to read is a matter of learning to crack a code.

In English, children need to be taught the relations between letters or letter combinations (graphemes) and the sounds (phonemes) in the language. This is very different from learning a whole new language – it is simply a way of coding the language they already know and speak. This point has an important consequence. There is no logic to the idea that learning to read should come “naturally” to children if they are placed in a literate environment, just like learning to speak. Children learning to read simply have to learn to map the written form of a language they already know well, onto its spoken form. As Gough and Hillinger (1980) put it: Learning to read is an “unnatural act”.

Luckily, children do not need to be taught every single written word or all conventions of the orthographic system. The point of the “self-teaching mechanism” (see e.g. Share, 1995) is that children are able to learn to identify new words on their own once they master the basic letter-sounds and how they blend to form spoken words. Of course, in order for the self-teaching mechanism to kick in, children need to be presented with books at an appropriate level for their ability: i.e. books that are sufficiently challenging (with some words that they have not come across before), but not too difficult.

The alphabetic code in English is notoriously difficult, but even the spelling of irregular words, like island or sword, is far from random. Almost all the letters correspond to sounds in the spoken word, with the exception of one silent letter in each of these words. So these irregularities should not be used as a justification for teaching children by a whole word method. When taught by a whole word method children do not become independent readers unless they extract the letter-sound rules for themselves – which they take an exceedingly long time to do (Brady, 2011; Seymour & Elder, 1986).

Some teachers are concerned that if children are taught by a sounding out/phonics approach, typically using decodable books (which might not have the most exciting storylines), then they might become overly focused on decoding, at the expense of comprehension. However, there is no evidence for this concern. In fact, children who have early, intensive training in phonics tend not only to be better at word reading later, but also to have superior comprehension skills (see e.g. National Reading Panel, 2000).

Even though children typically have a high level of communicative competence when they start school they do not have all the language skills in place that they need for text comprehension. It is a common misconception that, in order to develop competence in reading, beginning readers would need only to be taught to decode the written word, and then their language comprehension skills would kick in and they would be able to understand written texts just as well as they understand oral language. This is a misconception because it ignores the fact that written texts are, in important ways, different from spoken interactions (see “Written v...