![]()

PART ONE

1

Tentpole TV: The Comic Book

Ancillary products and branded transmedia texts clearly are not new to the television industry and can be found at least as far back as the Little Ricky Doll sold to young fans of I Love Lucy or Dragnet board games featuring the deadpan likeness of Jack Webb. Popular live-action television characters and formats have frequently graced the pages of American comic books with results as varied as DC Comics’ Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1960–4), Western Publishing’s Twilight Zone (1962–82), and Now Comics’ curious comic-book adaptation of Married with Children (1990–4). With few exceptions, these books were crafted exclusively by the comic-book producers with only financial coordination with the intellectual property (IP) owners; famously Western Publishing’s Italy-based artist for many of their Star Trek adaptations (1967–79), Alberto Giolitti, drafted his issues without ever having seen a single frame of the on-air television program ([Alberto Giolitti biography] n.d.).1

According to several pieces of publicity, the executive producers of tentpole TV have sought to more closely integrate the creative efforts of texts managed across media channels, constituting both a new creative-organizational role for these showrunners and a new economic model for exploiting television IP. In the first case, showrunners emphatically insist that the construction of these off-air texts remain close to what we call the creative core of the television serial, namely the writers. In October 2006, The New York Times ran a piece subtitled “Lost, Inc,” in which the author chronicled the extracurricular activities of Lost showrunners Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse overseeing and creating a flood of products outside the confines of their hit show proper—all of which the producers “in varying degrees, have a say in” (Manly 2006). Similarly, a March 2007 Wired article on Heroes showrunner Tim Kring quoted the writer-producer as stating, “my job has changed from being in the writing room and editing . . . to managing a brand,” again referring to creative work outside the boundaries of the show itself (Kushner 2007).

Near concurrent with this new flood of television-based products, Lindelof (2007) contributed an editorial to the The New York Times weighing in on the economic future of network television, beginning with the polemic sentence “television is dying.” The article is a defense of the then just beginning WGA (Writers Guild of America) strike that brings to bear the evidence that new media is not simply an experiment for network television to play with, but its inevitable future, a future demanding a new financial logic of production and compensation. Lindelof’s think piece also suggests that it is not only creative curiosity on the part of writers—as implied in the two previously cited articles—that has prompted a more aggressive posture toward ancillary products, but it has become an economic imperative for the survival of the “dying” medium. Kring, too, echoed this sentiment in a contemporary Fast Company article where the producer claimed that, “in five years the idea of broadcast will be gone” (Kushner 2008). In these articles and others like them, tentpole TV showrunners argue that exactly what constitutes a television program creatively, organizationally, and economically is under transition and is expanding. In these and similar statements, showrunners like Lindelof and Kring subtly position their own use of tentpole TV as a way out of this crisis.

Collectively, all these articles selectively highlight several changes in the production and economic processes of network TV that all point back to the same economic and theoretical motive: to make programming more streamable. Streamability—the ability to move creative products from one platform to another through either repurposing to different recording media or translating intellectual property into new conceptual and/or material objects—in the work of convergence theorist Simone Murray (2005) is cast as the cardinal virtue of contemporary media conglomerates. Murray argues that streamability is linked to the financial need to replace economies of scale, lost with the fragmentation of the homogenous model of the mass audience, with an economy of scope, achieved through clustering products around single brands and allowing products to effortlessly cross-promote one another. The core of Murray’s theory echoes the work of Henry Jenkins (2006) on transmedia, Jennifer Gillian on must-click-TV (2010), and James Bennett on television as digital media, all of which insist that contemporary television has evolved precisely in the way in which it has been able to increasingly migrate from the television set. While Murray’s theories are compelling, the author’s observations lack specificity. Network television producers achieve streamability when they, on the one hand, sell and purchase formats for inexpensive reality programs globally and, on the other, license the image of the hit shows to everyone from print publishers to theme parks. While each is a clear case of streaming in broad terms, the differences between each make such a wide categorization reductive.

In other words, streamability is sought and achieved through any number of strategies. It is my intention in the following to review and analyze two such comparable cases of network television shows streamed into another medium, namely comic books. I will examine how these two productions have attempted to answer the deceptively simple questions: What now constitutes a television show and how is it to be produced? To do this, we will investigate both the production of these comic books and their content as well as how both of these spheres influence one another. If nothing else, the self-proclaimed vigor with which tentpole TV showrunners are embracing unfamiliar ancillary fields implies the importance of meaning managed across different media into products that, as a result, cannot be simply dismissed out of hand as reproductions or derivatives. Ultimately, Lindelof, Kring, and Murray are chronicling the same easy process of translation and content streaming, albeit from vastly different intellectual traditions. It is my hypothesis that Murray’s concept of streamability and its public face, constituted in the image of tentpole TV programs projected by these programs’ showrunners, cleans up a process that involves the incorporation of work by distant creative professionals and the synchronization of their efforts in terms of both time and meaning, a process fraught with potential complications. More simply, I would like to messy up streamability and to consider the significance of this mess. Cultural products are not metal ingots that can be melted down and cast in a number of forms with little coordination. Each stage of translation is an interaction fraught with negotiation and consequence and these interactions can and should be studied in the course of cultural analysis.

In my own work, I would like to follow up on this complicated relation of producers and their texts through the application of the cultural theory of Clifford Geertz (1973) that will amend the more macroscopic, top-down view with a microscopic gaze interested in the qualitative life of cultural production. In my understanding of Geertz, cultural analysis involves the appreciation of the intrinsic double aspect of culture as both a model of the world in which a worldview is coded into symbol or formula in the manner of a chart or formula, and as a model for the world in which the symbolic material of culture is transmitted and redeployed in human behavior (95). In adapting this framework to network television, I would state that tentpole programs—that is those which have been used to maximize streamability through multiple articulations—provide both a model for how contemporary and so-called post-network business is to be made and a model of the way that these practices have influenced the work of creatives. A simple example: the work of transmedia producers on these programs rearticulates a certain division of labor through controlled information flows, creating a model for, while the use of secondary characters in these ancillary texts expresses and signifies the limitations and constraints of this division of labor, as the texts become a model of. This application of Geertz requires two adjustments. First, Geertz’s model of/for was originally meant to refer to culture as model of/for the world, in the largest sense of the word. When studying cultural industries, I delimit the “world” to the community of producers while bracketing out the meaning production done by eventual consumers for expediency’s sake. Similarly, Geertz’s original culture concept was an all-encompassing one universalized across an entire population. Popular culture producers play to a fluid and inconsistent audience. Thus, it makes the most practical sense to center the study on producers and their “world.” Ultimately, application of Geertz’s cultural theory also reflects the work of Paul Dimaggio’s (1977) cultural industries approach that insists that the “core characteristics of ‘mass culture’ can be seen as attributes of industries, not of societies” (437). In other words, popular culture texts, above all else, can be decoded as artifacts of their native societies, namely cultural producers.

In the following, I will be investigating questions of how streamability is achieved rather than exclusively why it is achieved—a query already handsomely postulated upon by thinkers like Murray—in the practice of network television as ancillary creatives become more central to programming. I have observed and will report on two attempts to use a separate cultural system to reconfigure the practices and routines of television production (model for) and to express and to discuss the inherent issues involved in this very expansion (model of). That is, we will consider the cases of the comic-book translations of two big-budget network TV tentpoles: Heroes and 24. Methodologically, my study was conducted through a combination of primary research through interviews and e-mail correspondences with the creatives involved and a supplementary review of trade literature in both the comics and the television industries as well as formal analyses of the comic books produced. Due to the vastly multi-sited nature of the industry studied, contact has been partial and intermittent. Ultimately, the picture that emerges of transmedia work will be an uneven one with sharp divides separating the creative core from a series of supervisors and freelancers, hired on a per-project basis to assemble a large share of transmedia’s extra work in comic books as well as the other media considered in subsequent chapters. Barriers are maintained and contact is minimized between creative nodes of transmedia production. Supervisors use mechanisms such as trust and informal contacts to minimize communication, while freelancers compensate this information blackout with their own fandom as well as ad hoc, improvised artistic choices. In the end, I will argue that this ambivalent division of labor that publicly brings transmedia collaborators closer to the creative core, but internally complicates this abridgement contributes to the dominant thematics at play in the resultant comic-book texts. Specifically, I will draw out the repeating attempts of these comic books to match their on-air antecedents through a near-constant interrogation and articulation of character motivation.

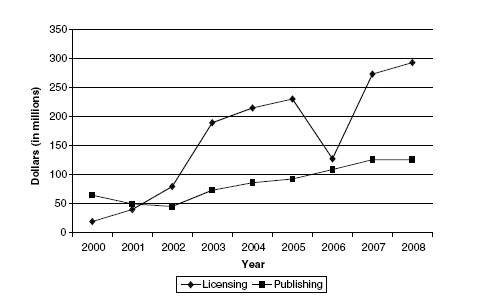

At the same time that network TV producers have become interested in expanding the worlds of their programming into the field of comic books, comic-book producers conversely have sought to move their product into new realms as well. While profits connected to physical book production (in both monthly pamphlets and trade collections) have only limited growth potential for comic-book producers, licensing of intellectual property to other media has become a much more significant source of income for comic-book producers. For example, during the first two quarters of 2006, Marvel Comics—the country’s largest producer by volume and market share—netted US$73.5 million and US$48.9 million from their licensing and publishing arms, respectively (Marvel 2007). These figures grew the following year, but at a vastly different clip resulting in US$148.2 million in licensing and US$60.5 in publishing, likely due to the performance of Sony’s licensed film Spider-Man 3 (Marvel 2007a) (see Figure 1.1). Moreover, the most fateful moments in this firm’s recent history (the struggle over the company in bankruptcy court and the recent formation of a movie-production arm, Marvel Studios) were resultant from controversies over the management of licensing (the noncompetitive deals over Marvel-licensed toys, the poor profit participation of Marvel in licensed feature films, and their eventual purchase by Disney in 2009) (Raviv 2002, Waxman 2007). Smaller publishers too have sought out increased rents on their IPs, particularly through the courting of feature film adaptations, resulting in a series of trade articles searching for the “next” Marvel to be mined and exploited in Hollywood (Graser 2007).

Moreover, the producers and supervisors behind 24 and Heroes are by no means the only television workers interested in the medium of comic books. Notably, writer Joss Whedon, the former showrunner of Buffy the Vampire-Slayer and the writer many credit with innovating the contemporary action serial, has “continued,” with the assistance of many of his staff writers, Buffy in a series of books published by Dark Horse Comics, subtitled “Season Eight” and “Season Nine” (Buffy concluded on-air in its seventh season) (Purdin 2006). Similarly, the prematurely cancelled serial Jericho was extended but not concluded by a comic-book series, produced by both Dynamite and IDW Comics, subtitled “Season Three: Civil War.” Both Warner Brothers–produced Supernatural and Chuck have been adapted for the imprint Wildstorm, a division of DC Comics (also owned by Warner Brothers). IDW also has published adaptations of CBS’s CSI as well as FOX’s The Shield and Angel.

Beginning in July 2004, comic-book publisher IDW began to produce books based on the FOX-Imagine program 24 and in September 2006, publisher Aspen MLT began to produce a series of webcomics for the NBC program Heroes. What these two ventures have in common is that they both operate via a combination of freelance creative labor and permanent supervision either closely or loosely affiliated with program producers. In the case of Heroes, scripts are drafted by either series writers, staff writing assistants, or freelance writers hired from outside the program staff. Yet, in all these cases, it is the series writers who oversee and determine the content of each issue. The remaining artistic duties on the series (penciling, inking, coloring) are performed by freelance workers on a project-by-project basis that are, in turn, overseen by Aspen’s own editors. The production of the comic-book version of 24 is arranged in a slightly different manner. FOX’s licensing and merchandising department oversees the project while both the writing and the artwork originate from outside the show proper and outside IDW itself, which, like Aspen, retains very little permanent artistic staff.

FIGURE 1.1 Marvel Comic sales.

Heroes’ writer-producer and transmedia advocate Jesse Alexander recently commented upon the Heroes staff involvement in its ancillary manifestations stating, “[participation is] critical because if you play in this space, you’re opening yourself up to the risk of catastrophe from one small mistake” (Kushner 2008). Yet, despite claims of this sort, actual interaction between supervisors and freelancers in the cases of both the Heroes and the 24 comic books is relatively rare. Indeed, the minimization of supervisor contact is a pronounced implicit goal running throughout my observations on the production of each comic-book series. The fact that freelancers are hired short term, per project, facilitates this minimized interaction. I suspect that these efforts could be attributed to several motives. First, minimizing contact is economically rational. Supervisors see no additional fees for reviewing revised content and thus seem less likely to review successive drafts. Minimizing contact also embodies an organizational logic that seeks to free creative resources from being overburdened on single projects, especially when the project is more textually and economically tangential. One writer for 24 comic book recently told me that interaction with licensors is infrequent simply because they “don’t want to get bogged down with that kind of detail.”2

This leaves us with a paradoxical understanding of brand expansion in which supervisors are deeply invested in the work of freelancers—remember that television is dying—but are reluctant to invest themselves entirely. What often stands in for contact, I argue, is the cultivation of trust. Trust, as a theme, has been revisited by several recent social theorists who have noted increasing levels of complexity and uncertainty in contemporary social life that have led not to the submission of actors to the laws of pure rationality and order, but to the use of trust in facilitating social action (Luhmann 1979, Giddens 1991, Sztompka 1999). Anthony Giddens (1991) goes the furthest by suggesting that it is trust in others, derived from infantile experience, which gives an individual a “protective cocoon” that shields the social actor from the pitfalls of rampant existential self-questioning and helps to establish a consistent, reflexive self-identity (36–42). Borrowing on these authors, I use the term trust in our case study in a very specific way. While trust can equally refer to being entrusted, that is to be brought closer to an organizational center through the sharing of resources, I am following Giddens’s lead by using the term more in the manner of faith, faith in personnel that assures the party bestowing trust that a task will be met by the trustee without the need for constant interaction. Extrapolating to our case, increasing complexity and uncertainty in the production of television, particularly as it pertains to its porous, transmedia boundaries (an “identity crisis” of sorts), has producers cultivate trust in their freelancers to hold onto their own ontology security, their own sense of the television program as a cohesive, creative act. However, each instance of trust is both a way to eliminate anxiety of uncertainty at the same time that it is a constant reminder of the risk that lies beneath, an observation that could go a long way in explaining the bifurcated behavior of tentpole TV supervisors. Put in more concrete language, television producers are aware of the need to expand the brand beyond the program and invest trust in experienced professionals in other fields to do this, but in each effort, producers risk the possibility of exposing their ignorance of new or other media forms or possible failure. Or, as Erving Goffman (1971) observed (in a vastly different context), “the conditions that allow one to develop trust anew at each contact expose one to all times to sudden cause for doubt” (18). To interject a mundane example: The less I know all the things that could go wrong with my car, the more I can trust it to start every morning. The importance of trust also has a less high-minded place in this equation. Simply put, the more supervisors trust a freelancer, the less they are obligated to maintain contact; the two variables have an inverse relationship.

Outside of speculating on motive, we can examine how this minimization of contact and a simultaneous cultivation of trust are achieved. Supervisors focus interaction with and input for freelancers on the preproduction of texts. This minimizes subsequent interaction by establishing a minimum trust between permanent and temporary workers thr...