eBook - ePub

Inside the Battle of Algiers

Memoir of a Woman Freedom Fighter

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This gripping insider's account chronicles how and why a young woman in 1950s Algiers joined the armed wing of Algeria's national liberation movement to combat her country's French occupiers. When the movement's leaders turned to Drif and her female colleagues to conduct attacks in retaliation for French aggression against the local population, they leapt at the chance. Their actions were later portrayed in Gillo Pontecorvo's famed film

The Battle of Algiers. When first published in French in 2013, this intimate memoir was met with great acclaim and no small amount of controversy. It is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand not only the anti-colonial struggles of the 20th century and their relevance today, but also the specific challenges that women often confronted (and overcame) in those movements.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inside the Battle of Algiers by Zohra Drif, Andrew G. Farrand in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

IN THE FAMILIAL EMBRACE

My Lineage

I was born in Tiaret, on the Sersou plain, on December 28, 1934. In the Islamic calendar, that day fell during the holy month of Ramadan. The farm where I was born belonged to my grandfather, Hadj Abdessalem Drif.1

My paternal great-grandfather, Hadj Moulay Tayeb, had married in his home region and waited in vain for years to have children. Sometime in his forties, he grew desperate and decided to divorce his wife, who was evidently infertile. After dividing up his lands and belongings among his brothers and sisters, he secluded himself in the zawiya2 of his ancestors—the zawiya of Moulay Idriss, in Volubilis, Morocco3—and dedicated himself to contemplation and seclusion. This radical decision was not an act of reprisal against his wife, with whom he had been very fair when dividing his wealth. Rather, it was a decision rooted in his religious beliefs, which were deeply Sufi.4 He believed that God, by not granting him any descendants, was sending him a message instructing him to cut ties with his earthly possessions and to dedicate himself to contemplation and seclusion in the hermitage. So that was what he did.

At the mausoleum, whose moqaddem, or caretaker, was named Hadj Abdessalem, he devoted himself body and soul to total contemplation. It is said that during his seclusion, one evening he dreamed a particularly disturbing dream. He recounted it to the moqaddem, asking him to reveal its hidden meaning. The moqaddem replied, “I can assure you that what you have witnessed last night was no dream. It was a ro’ya—a vision. God has measured your piety and sincerity and decided to reward you. You must return to your homeland and to your local zawiya. You will ask for the hand of a young woman named Halima. Marry her and she will give you a son, whom you will name Abdessalem, and he will bring you many descendants.”

He set out immediately. Back on the Sersou plain, he married my great-grandmother, who gave birth to my grandfather. But my great-grandfather was already an old man, and he died when my grandfather was just two years old. My grandfather was raised and educated by his mother’s family at the zawiya of Sidi M’hamed Ben Amar, where he later married my grandmother Zohra, who gave him thirteen children, including my father, Ahmed. It is important to note that until the nineteenth century the zawiyas were the center of our education system; it was there that languages, law and fiqh (jurisprudence), history, geography, mathematics, and medicine were taught.

That was where my father got his start, completing his primary education in the Sersou before moving to Tlemcen for the equivalent of his secondary schooling at the Sidi Boumediene zawiya. He would study there for seven years before joining the Sidi Abderrahmane medersa in Algiers, where he would complete a third phase of his studies and earn the diploma that allowed him to reach the prestigious—but ever-so-difficult—rank of qadi, or judge. To ensure that he wouldn’t be blocked by the colonial administration, in parallel to his training in Islamic law he also studied at the Faculty of Arts at the University of Algiers, earning a diploma there as well. All this is to say that my father was a true scholar who had mastered two intellectual cultures. After his considerable academic training he climbed the ranks, from aoun (assistant clerk) to adel (clerk) to bach adel (deputy judge) before finally reaching the post of qadi.

Like my father’s family, who derived their power and social authority from the importance of the zawiya, my mother’s family enjoyed a similarly important religious and economic influence. My maternal grandfather, Hadj Djelloul Ben Ziane, was a descendant of the Zianid dynasty, affiliated with the Sidi M’hammed Ben Choaïb zawiya in Sidi El Hosni, near Tiaret. He reigned over an immense fortune, derived mostly from hundreds of hectares of fertile land and thousands of head of cattle and horses. My maternal grandfather was an incorrigible polygamist, and my grandmother Arbia, renowned for her great beauty, was his last wife. She had a single daughter—my mother, Saadia—with her husband before divorcing him when she could no longer stand his polygamy or his tyranny. Coming from a wealthy family herself, she felt she had everything to gain by reclaiming her freedom. My mother grew up pampered by her two families, who instilled in her their culture and traditions and raised her to protect and champion them, which she did until her very last breath. Before we even reached school age, for example, she forced us to learn to recite our lineage by heart.

From her origins in a family of wealthy landowners, my mother also gained a keen business sense. She oversaw the affairs of the household, where she reigned supreme over all, including land holdings, livestock, and various commercial ventures. From the age of ten, my brother Abdelkader was her intermediary with any outside associates. She taught him the secrets of the trade and saw to it that he exercised them with the utmost rigor and professionalism. My father, busy with law and literature and naturally scornful of the trivialities of material existence, would have found it hard to believe that many of the notables who sought his notarial services or legal counsel were also conducting business with his wife, who never even left the house.

My parents had eight children: five boys and three girls. I am the second, having come into the world a century and four years after the colonization of my country. In material terms I led a pampered childhood, and I was emotionally and culturally nourished by the saga of my maternal and paternal ancestral lines, taught to me by the best teacher in the subject—my mother. I knew from a young age who and where I was: an Algerian in her own country. I also knew early on that my land was occupied, seized for no purpose other than rape and theft, and that the roumi—the Roman, that foreigner from the north—was both the rapist and the thief. I lived every moment with such an acute awareness of this fact that it became like my skin, my blood, or the beating of my heart, and was frequently revived by events around me. As a child, when I accompanied my mother and my aunts, traipsing together across vast fields to visit the tomb of a wali salah—a local patron saint—the women explained to me that in truth these lands belonged to such-and-such tribe, which had been dispossessed in favor of such-and-such colonist. In doing so, they transmitted to us the history, sociology, and true map of our country.

Similarly, when the European doctor was summoned to tend to my father’s fever, my mother explained to me why she was allowed to show herself before him, even though she hid herself from Muslim men. It was entirely unthinkable, she explained, that the doctor, as a roumi, could constitute a potential spouse or engage in any other type of relationship. Through this “cultural sentencing,” my mother condemned him to the status of a eunuch.

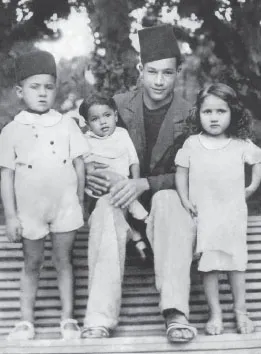

Zohra Drif, right, with her Uncle Abdelkader and two siblings

By now it is clear to me that my mother—along with all the women of my family—played a decisive role in shaping who I would become. I am eternally grateful to them.

About My Mother

As an orphan, my grandfather Hadj Abdessalem was raised by his maternal uncle, Hadj Tahar, head of the Sidi Abbas Ben Ammar zawiya and of the Ouled Qoraïch tribe. One day, when he was visiting his friend Hadj Djelloul Ben Ziane, my grandfather’s uncle saw a young girl playing in the courtyard. Hadj Djelloul’s young daughter Saadia, then only seven years old, was beautiful and already lively and sociable. She ably managed the traditional greetings to welcome her father’s friend for the first time. Pleasantly surprised and moved, Hadj Tahar put his hand on the girl’s head and, addressing his friend, asked him to promise her to his thirteen-year-old nephew Ahmed, then just a student. Saadia’s father could not refuse his friend Hadj Tahar a thing, so he gave him his word.

From an economic perspective, this union was perhaps a poor choice for Hadj Djelloul. Saadia’s father was a religious notable and major landowner with sizable herds of livestock, while Hadj Tahar and his family were well regarded only for the nobility of their ancestry.

Five years later, Ahmed, then eighteen, was studying at Sidi Boumediene, the renowned medersa in Tlemcen, when my paternal grandfather brought the promised child into his family to allow her time to adjust to her future husband’s home. Having not yet reached puberty, she still played with dolls, and at first did not realize that she was changing homes in order to marry and assume responsibilities far too weighty for her young age. She passed those final years before reaching maturity playing with the little Drif girls her age, all the while being prepared by the women of the house to assume her future role. Once she reached puberty, in 1930, they were married and a joyous party commemorated the union; the young couple then only saw one another during my father’s school holidays. My parents lived this way for six years: my father studying first in Tlemcen, then in Algiers, and my mother living among her in-laws. During those six years, two girls were born but did not live, followed by my brother Mohamed and then me.

Saadia Drif, Zohra’s mother

One event deserves mention because it shows my mother’s strong character and determination. Since her marriage, every Monday—market day—my maternal grandfather, Hadj Djelloul, had visited his daughter and brought her a small piece of jewelry. Her sisters-in-law (my paternal aunts), jealous to see her with so many rich gifts, mocked her as well as my grandfather for bad taste. So on the day after each of her father’s visits, my mother began to return the gifts to the local jeweler. After several months of this, Hadj Djelloul pieced it together.

One Monday, he arrived unannounced at the Drif home and surprised his beloved daughter, who was bowed under the weight of the family’s laundry. He flew into a fit of rage at the sight of his daughter subjected to the labor typically reserved for her servants—in sharp contrast to her rightful social standing—and announced his immediate decision to bring her and her two children home, all the while screaming at the Drif family, “I entrusted you with my favorite daughter, not with a servant girl!”

My brother Mohamed and I followed our mother and spent the ensuing months frolicking in what appeared to us a paradise—a spacious house on a huge property full of horses, sheep, and all manner of pets. Our living conditions had changed dramatically. We wanted for nothing until the day my father, having finished his studies, arrived from Algiers to demand his wife and children back.

Saadia, then a young mother barely twenty years old, was as attached to her own father and family as she was to her husband and children. Yet she found herself obliged to make an impossible choice: to follow her husband and definitively cut ties with her roots, or to go the other way. She did not hesitate, despite all the pressures from her own family, in choosing to join her husband. At the time this was an act of considerable courage, and of modernity. Her choice empowered my father to free himself from his own clan’s oversight as well. In this way, my parents, Saadia and Ahmed Drif, settled in Tissemsilt and founded a home independent of their two families. It was a revolution against our country’s traditions of social organization. We had left the extended family, centered closely around the patriarch, and become a nuclear family, all the while trying not to break from traditional society completely.

In Tissemsilt (which was called Vialar during the colonial times), they sent me to kindergarten, where I was made to memorize songs praising the glory of some marshal. I knew nothing of all this—not even the language. I was the only “native” in the class. Every morning I copied what my classmates did, standing in front of a flag I didn’t know with no idea what it stood for, intoning, “Maréchal-nous-voici-nous-voilà-devant-toi.”

When I returned home, I told my mother everything I had been taught. She proceeded to give me a full cultural debriefing: The flag was that of a foreign country, France, and the marshal was their leader. As for us, we were Algerians and our country was Algeria. She explained to me that the French were unwelcome occupiers, strangers to our land, our people, our religion, our language, our culture, our history. She launched into a wonderful description—worthy of the finest tales of sultans and princesses—of our ancestors, from the most distant to the very recent.

Thanks to these lessons, when I entered the Vialar elementary school at six years old, I knew that every day I was traveling between two completely different and opposing worlds—the world of my mother and the world of the French school.

At home, where my mother reigned, it was completely Algerian, with our customs, our traditions, our Arabic language, our religion of Islam, our lifestyle, our history, our ancestors, and even our mythology. At school, in the outside world, France ruled, with its language, its flag, its religion, its history, and its mythology.

For nearly five years, I was the only little “native” girl at school, with my big long braids and long skirts reaching to my ankles, among the crowd (which to me seemed huge) of little European girls with their short hair and their little dresses above the knee—so short, in fact, that when they knelt they often revealed little behinds sheathed in white underwear—along with white socks and black ballet flats. The difference between me and this crowd even extended to the foods we ate at ten o’clock in the playground: they pulled out a brioche here, a croissant there, sometimes a chocolate croissant or, for the more modest, a hunk of Parisian baguette with jam or some similar European garnish.

As for me, I had my Algerian treats—maqrouta, mbardja, msemna, and, when my mother was short on time, a large slab of matloue bread with our family’s honey. For a long time I didn’t understand why or even how my classmates could prefer my foods over their own. It took me a long time to discover for myself just how right they were to prefer our msemen, kneaded by expert hands and impossible to buy outside the home. But it was hard for a child to live, alone and peculiar, in a foreign world.

Nonetheless, I completed my primary-school years as an excellent student, finishing tied for first place in my class with my classmate Roselyne Garcia. I considered Roselyne a dear f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Lakhdar Brahimi

- Maps (Algiers and Algeria)

- 1 In the Familial Embrace

- 2 Awakening

- 3 First Contact with the FLN

- 4 Into the Heart of the Armed Struggle

- 5 In the Casbah

- 6 Bringing the Algerian Question to the Global Stage

- 7 The Eight-Day Strike

- 8 Desperate Times

- 9 The Arrest

- Glossary

- About the Author

- Acknowledgments