- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

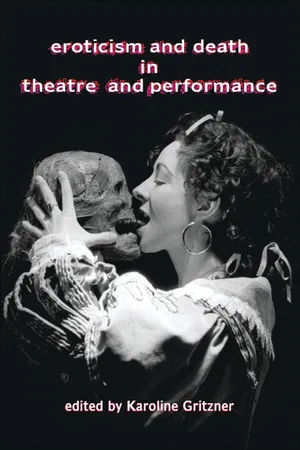

Eroticism and Death in Theatre and Performance

About this book

Exploring a range of topics, including Greek tragedy, Shakespearean theater, contemporary British plays, opera, and the theatricality of Parisian culture, this compilation provides new perspectives on the relationship between Eros and Death in a series of dramatic texts, theatrical practices, and cultural performances. Detailed and analytical, these informative essays demonstrate how changing attitudes towards sexuality and death—opposed but entangled passions—were reflected in theater throughout the course of history. Psychoanalytical and philosophical models are also referenced in this work that features essays from dramatists Dic Edwards, David Ian Rabey, and David Rudkin.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eroticism and Death in Theatre and Performance by Karoline Gritzner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Some Erōs–Thanatos interfaces in Attic Tragedy

David Rudkin

First, some definition: Erōs and Thanatos, not in Freudian metaphorical sense but in Greek immediate sense – ‘έϱως as the sexual drive, θάνατος as death itself. And if I speak of ‘Attic’ rather than ‘Greek’ Tragedy, it is because the more traditional term, while perfectly respectable, yet suggests a background of a single ‘Greek’ cultural unity, which there was not at this time. Our entire surviving corpus of Tragedy ‘in Greek’ was written from within a context of one regional dialect – that of Attica – and produced for the civic/religious festivals of its city Athens during her near-century of political and naval dominance. Where extant Tragedy is concerned, we are talking of a short time-span: from 472 BCE to 406 or soon thereafter; from the heady aftermath of the Athens-led victory over Xerxes of Persia to the years of her fall and the dismantling of her democracy.

I shall discuss four characters from what little we possess of Attic Tragedy: the princess Iphigenia, offered as a human sacrifice; an orphan daughter of King Oedipus, Antigone, who, rather than betray a ‘higher law’, submits to the sentence of death; a young queen married into a foreign land, Phaedra, afflicted with transgressive Erōs; and the object of her desire, her stepson Hippolytus, who repudiates Erōs altogether. With each of these characters, we shall find Erōs or an Erōs schema coming to logical consummation in unnatural death.

For our first figure, Iphigenia, it all begins, as it shall end, at Aulis – the deep narrows of a natural harbour on the Aegean coast of Greece. Here, two Bronze Age warlords, Agamemnon of Mycene and his brother, the king of Sparta, have assembled a mighty force to embark for a punitive war against the Asian city of Troy. Punitive because, while a Trojan prince was recently a guest in Sparta, he had seduced and taken back home with him the Spartan queen. The Greek forces – with their legendary ‘thousand ships’ – are to deliver retribution on the Trojans, and, at whatever human cost to the Trojans and to themselves, recover Queen Helen and their own insulted pride. But their thousand ships cannot sail, because day after day north-easterlies are blowing, pinning them in the sound. This is the situation as given in our oldest Tragic source for it, the opening play in the trilogy conventionally known now as the Oresteia. The Aeschylus text vividly suggests the atmosphere at Aulis caused by the prolonged delay: the impending disaffection, desertion, mutiny. The military priest and prophet Calchas attributes the adverse winds to the wrath of the goddess Artemis. If she is to be prevailed upon to still these winds, and release the ships, she will exact a high price. Precisely what, is not spelled out; but the inference is soon clear. For Agamemnon to have his war, he must offer Artemis in sacrifice his own eldest child.

Why should Artemis require this? If we are to understand her wrath at our distance of 2,500 years, we need to try to understand something of Artemis herself. So far as concerns the events at Aulis, and to start from the traditional simplicities, Artemis is, among other aspects, ‘goddess “of” virginity’. This ‘goddess-of-x’ formula is a very crude equation, particularly with Artemis. We do better to think of the virgin estate – in girl or boy – as her domain. The virgin girl or boy is a sacred property of that domain; thus to harm one would arouse her wrath. There is an obverse to this: to sacrifice to her a virgin child, duly consecrated, would be to make a very high order of offering. But to the Oresteia audience, human sacrifice is not a historical memory. It might at times, as here, intrude into their mythology, but it is a barbarity to them. So what sort of ‘presence’ is this Artemis in their lives, that in this story, in this play, she could plausibly demand the ritual slaughter of an innocent child? How is that consistent with the Artemis they know?

The more we consider Artemis, the more aspects to her do we find. Her ‘virgin’ domain extends naturally enough to all the untouched wilderness and untamed creatures there, hence her identification with the hunt: it takes place on her territory, and needs to be conducted with due deference to her. What to us seems contradictory at first is that this ‘huntress virgin’ ordains also the domain of pregnancy and childbirth. In Greek common parlance of those times, the pains of labour were ‘the arrows of Artemis’. This apparent contradiction retires somewhat once we envision Artemis as her archetype, a Moon-goddess. She is Apollo’s sister, and, unlike her brother-god the consistent Sun with his vitalising light and warmth, the Moon is a cold presence, separate-seeming from us, aloof, shifting shape, keeping her dark side ever hidden from us – metaphorically virgin indeed, yet, in that very rhythm of her phases, visibly ordaining a woman’s body-cycle of menstruation and birth. She is, as Moon, herself inviolable, causing us necessary pain of life – and as Artemis, physically ‘out there’ somewhere beyond our city wall in her untamed wild, where it could be all too easy to cross her and offend her. Something such had happened on the road to Aulis.

Aeschylus does not stage the scene at Aulis. It has all happened ten years before the play begins. As the senators of Agamemnon’s royal city make their ceremonial first entrance onto the space, they give us an exposition, on a massive scale, of the issues and perplexities that will drive the whole trilogy: is there a moral function to human suffering? Is there an ultimate rightness at work in the universe? In the greater pattern of things, what is the role of individual human will? This is not philosophical abstraction: there are motifs at work, phrases, words, that will recur, mutate and evolve quite symphonically throughout the onward organic process of the trilogy. All this exposition is orchestrated in song and dance, deploying a range of highly formalised metrical schemes and (we presume) musical modes. The language is difficult, its syntax often condensed and elliptical, its vocabulary double-edged, at times chimerical. How much of this in performance would an Athenian audience have distinctly heard, let alone understood, we are at liberty to doubt. But what the reverend seigneurs of Mycene are telling us – they say they were witness to most of this – is that at Aulis the two commanders are warned that Artemis is enraged, not so much by their intended war as by their moral evasion of the meaning and consequences of that war. As they had set out with their forces on the march to Aulis, there appeared a hideous portent by their road: two eagles tearing at a pregnant hare in the very moment that her young are being born. The eagles, one a golden, the other a white-tail, are identified by these attributes as Agamemnon and his lesser brother. Eagle-like, they will fall on Troy; Zeus has sent them – that is, their cause is just. But their prey, a helpless creature of the wild, giving birth, and her ravaged new-born young, are emphatically in the domain of Artemis. Likewise, the helpless mothers and children of Troy: they too are in the domain of Artemis.

Immediately a question presents itself. If – as the prophet Calchas insists – Artemis is ‘revolted by the eagles’ feast’,1 why does she require in propitiation an even more revolting act? More revolting, because while what the eagles are doing is true to their created nature – the Elders call them the ‘winged hounds of Zeus’2 – is it equally true to Agamemnon’s human nature to sacrifice his own daughter?

I think at Aulis we come near to a liminal moment in the world story-pattern of human sacrifice. Early in the Old Testament, when the Lord bids Abraham go into the land of Moriah, and on a mountain there sacrifice Isaac, his own son,3 that father will learn instead that Yahweh is no longer pleased with human sacrifice, and will be content with the ram from the thicket. It is a moment of change that will distinguish the Children of Israel from all the other peoples around them, still passing their children through the fires to Moloch and the rest. Is Agamemnon at such a moment? To put it in our own anachronistic existentialist way: is Artemis offering Agamemnon a chance to think again? Surely Agamemnon could do otherwise. He could refuse to pay the price that Artemis demands. He could publicly put human sacrifice behind him, into the cultural past, as Abraham does; and his culture would take a major evolutionary step forward. He must then, to be logical, repudiate his war – or at least his part in it. The cost to him would be terminal; to his authority, his pride, perhaps even his life. And he has of course no way of knowing, if he refuses Artemis her sacrifice, how catastrophic her response might be. By comparison, Yahweh made it simple for Abraham. For Agamemnon, much more is unknown; as he sees it, he has only a choice of evils: to ‘murder his own child, the glory of his house’,4 or to be a lipónaus, a deserter, and betray his allies. In practice, he sees that he has no choice: he takes on, in a famous Aeschylean phrase, the anánkēs lépadnon – the ‘yoke of what he must’5 – and agrees to the sacrifice. So Iphigenia comes to Aulis.

The Elders, in their elliptical, allusive Aeschylean mode, give us mind’seye glimpses of the scene, almost like a montage of film stills. The overall informing image is of the victim held high, horizontal above the altar, face down; one man grips her by her ankles, another holds her around the waist, a third by her shoulders; her throat is exposed to the sacrificial knife; the officiant holds a bowl to catch the spurt of blood from the severed carotid artery. The Elders tell us of Iphigenia held just so, ‘like a goat-kid’,6 face down above the altar, her mouth stopped with a gag to staunch any curse from her that might bring ill upon her family. Her girdle is ‘violently’ undone, her saffron-dyed garment spills to the ground. Yet even in her nakedness, she is prépousa, ‘seemly’, the Elders say, ‘as in a painting’.7 She casts on those about to slaughter her a piteous look; she struggles to speak, but the voice that, by her father’s table in the men’s quarters at home once sang to him in ‘virgin’ song, is gagged.

Prépousa: we note the Elders’ cautionary emphasis on her ‘seemliness’. Iphigenia herself, so physically constrained, can do nothing to shield her nakedness. It is more as though the Elders (i.e. the poet) were doing that for us. It suggests a cultural anxiety to cancel the sexuality of the victim, to preclude inappropriate thoughts. A later poet will be more specific: when, some thirty years on, Euripides comes to describe a similar scene, the sacrifice of a Trojan princess, he will have her taking care to fall ‘with propriety, and hide what should be hidden from men’s eyes’.8 But this very caution inevitably touches a sexual note.

And here with Iphigenia that note sounds on. Silenced, the Elders say, is the voice that once sang in ‘virgin’ song. An objective observation, and poignant – but Aeschylus’s word-choice for ‘virgin’ here is rustic and dark: ataúrōtos – ‘unbulled’.9 Likewise with the natural reference to that voice singing in ‘the men’s quarters’: boundaries demarking masculine and feminine territories, socially and at home, are strict; yet even this objective social allusion serves further to remind us of Iphigenia’s sexual vulnerability. And in the very image of her brought among the army at Aulis, masculine territory, the primary cultural resonance is of a young girl leaving her maiden estate. To the Athenian audience, and many an audience since, Iphigenia is her father’s property. Against such background, her father would normally be ritually handing her over to be the property of a husband. The marriage-resonance is further enhanced by two little words: krókou baphàs – her garments are ‘saffron-dyed’.10 In Aeschylus’s compacted verse, there is no space for irrelevant detail. Saffron is for festal wear. Traditionally, in saffron, Iphigenia would be coming as a bride. Intimations of a wedding, then, contextually exist: the socialisation of Erōs. But here is a marriage where the bride is brought to die.

Fifty years later, the Aulis story will be given a play of its own, and here the wedding scenario is explicit. Iphigenia at Aulis is Euripides’s last play, left unfinished, completed we are told by his son, and our text now showing signs of further interference by a later hand. For Euripides – for simplicity we’ll call its author that – it is specifically to be married that Iphigenia comes to Aulis. At least, that is what she has been led to believe. The wretched Agamemnon, torn between his human nature as m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1. Some Erōs–Thanatos interfaces in Attic Tragedy

- 2. Dying for love: the tragicomedy of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra

- 3. Desire and destruction in the drama of Georg Büchner

- 4. Labyrinths of the taboo: theatrical journeys of eroticism and death in Parisian culture

- 5. The kiss of love and death: Eros and Thanatos in the opera

- 6. Eros/sex, death/murder: sensuality, homicide and culture in Musil, Brecht and the Neue Sachlichkeit

- 7. The living corpse: a metaphysic for theatre

- 8. Flirting with disaster

- 9. Howard Barker’s ‘monstrous assaults’: eroticism, death and the antique text

- 10. ‘Welcome to the house of fun’: Eros, Thanatos and the uncanny in grand illusions

- 11. Visions of Xs: experiencing La Fura dels Baus’s XXX and Ron Athey’s Solar Anus

- 12. La petite mort: erotic encounters in One to One performance

- 13. Saint Nick: a parallax view of Nick Cave

- 14. Afterword: The corpse and its sexuality

- Bibliography

- Index