eBook - ePub

The County Community in Seventeenth Century England and Wales

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The County Community in Seventeenth Century England and Wales

About this book

Honoring the memory of Professor Alan Everitt—who advanced the fruitful notion of the "county community" during the 17th century—this volume proposes some modifications to Everitt's influential hypotheses in the light of the best recent scholarship. With an important reevaluation of political engagement in civil war Kent and an assessment of numerous midland and southern counties as well as Wales, this record evaluates the extraordinary impact of Everitt's book and the debate it provoked. Comprehensive and enlightening, this collection suggests future directions for research into the relationship between the center and localities in 17th-century England.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The County Community in Seventeenth Century England and Wales by Jacqueline Eales,Andrew Hopper, Jacqueline Eales, Andrew Hopper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Alan Everitt and The community of Kent revisited

JACQUELINE EALES

The publication of Alan Everitt’s The community of Kent and the Great Rebellion, 1640-60 in 1966 was a major landmark in the historiography of the English civil wars. Everitt noted in his introduction that ‘we have tended too much to look at the period through the eyes of the government, and especially of parliament’. He focused instead on the county gentry - the community of his title - and described the ‘most striking political feature’ of the county as its insularity. Kent was moderately royalist and sympathised more with Charles I than parliament, while the committed royalists and parliamentarians were extremist minorities. Yet it fell into the ‘vice-like grip of parliamentary control’ because of its strategic importance: parliament ‘simply could not afford to countenance rebellion so close at hand’, as he phrased it. He saw parliamentarianism as an outside imposition from the centre, whose unpopular leading adherents such as Sir Michael Livesey, the regicide and military commander, and Sir Anthony Weldon, the chairman of the parliamentarian county committee (Figure 1.1), maintained control through force and violence.1

The community of Kent was the first history of Kent during the civil wars to be published since Henry Abell’s Kent and the great civil war in 1901, and it became a model for the study of other counties for a decade and a half.2 A spate of printed monographs and doctoral dissertations investigated the gentry in civil-war Cheshire, Worcestershire, Sussex, Shropshire and Berkshire, among others.3 While some of these studies observed differences to Kent, it was not until 1980 that a full-scale critique was launched in a seminal article by Clive Holmes, who argued that Everitt had overemphasised the insularity of the county, overlooked ideological differences among the gentry and assumed that their views represented those of the entire population of the shire. Holmes countered this narrow model by emphasising that the views of groups of peasants and craftsmen, who formed political opinions and expressed them, also had to be recognised in order to explain the events of the civil wars. The concept of the county community was also reassessed by Ann Hughes in her study of Warwickshire, in which she emphasised the economic, regional, religious and social connections that transcended county borders.4 Their insights coincided with the publication of another important article by David Underdown on popular allegiance during the civil wars and together these historians had a major impact on subsequent research.5 Studies of civil-war Devon and Gloucestershire, among others, reflected this shift of emphasis by investigating the political engagement of other social groups and even embraced gender by considering the role of women.6 Work on Herefordshire also analysed how the gentry collaborated with the clergy to influence local opinion during the civil wars.7 Nearly half a century after the publication of Alan Everitt’s influential work how then should these wide-ranging revisions be applied to the history of Kent?

Figure 1.1 Sir Anthony Weldon (1583-1648). Special Collections of the University of Leicester, Fairclough Collection, EP42B/7.

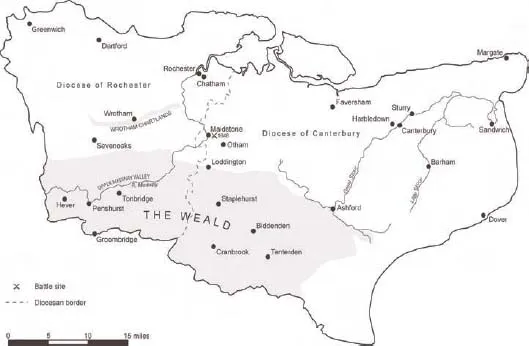

We should start by considering whether the concept of the county community remains a meaningful category, if it is no longer to be seen simply as an alternative term for the gentry. Traditionally the county has been regarded as a clearly defined political unit with sheriffs, deputy lieutenants and justices of the peace all being chosen to govern and maintain order within its borders.8 This use of the county as a focus for the collection of taxation, raising of conscripts and dispensation of justice was maintained throughout the 1640s and 1650s. During this period the committee system was extended from Westminster to the counties and Kent was governed by a central county committee and its sub-committees.9 In early seventeenth-century Kent there were also some notable internal administrative divisions, as the quarter sessions for the west of the county were held at Maidstone and those for the east were held at Canterbury. Kent also contained two entire dioceses within its borders in the sees of Rochester and Canterbury (Figure 1.2). Despite this fragmentation, the assembly of the gentry, the clergy and the grand jury (chosen largely from minor gentry and freemen) at the biannual assize meetings was regarded as representative of the county as a whole.10 The famous royalist Kentish Petition of 1642, devised in Maidstone at the March assizes of that year, was thus couched as the ‘humble petition of the Gentry, Ministers and Commonalty for the County of Kent agreed upon at the General Assizes for the County’. The emphasis on the approval of the clergy in this and other petitions is significant and will be investigated more fully below.

Figure 1.2 Map of Kent. © Canterbury Christ Church University, cartography John Hills.

The petition was drawn up by the recently expelled MP for Kent, Sir Edward Dering (Figure 1.3), and other gentlemen, and here we can see Everitt’s notion of the opinions of the royalist gentry as representative of ‘county’ sentiment in action.11 Parliament had just passed an ordinance without the consent of Charles I, which transferred the control of the militia from the king into its own hands. Dering’s petition thus called for a militia bill and emphasised that ‘the precious liberties of the subject’ should be preserved by ensuring that no order was to be enforced until it had been fully enacted by both the king and parliament. It also supported the bishops and the established liturgy of the Church as set out in the Book of common prayer, attacked the ‘schismaticall and seditious Sermons’ of parliament’s clerical supporters and demanded a law against lay preachers.12 Everitt erroneously regarded the Kentish Petition as ‘mildly royalist’, but S.R. Gardiner, the great Victorian historian of the early Stuart period, thought that it was central to the royalist political platform. He concluded that the petition embodied ‘the spirit which was soon to animate the King’s supporters in the Civil War’. This included a ‘newly awakened zeal’ for the king’s prerogative, which the royalists believed should be used to destroy the puritan opposition to the established Church.13 The House of Commons did not regard the petition as a mild document: it ordered the common hangman to burn copies and threatened Dering with impeachment.14

Figure 1.3 Sir Edward Dering (1598-1644). Special Collections of the University of Leicester, Fairclough Collection, EP41B - Box 1.

The promotion of the Kentish petition at the county assizes was an important gesture: it was in this public arena that the grievances of the county were traditionally presented by the grand jurymen and this gave Bering’s petition a further air of legitimacy. In 1648 petitioners from Kent stated that the grand jury ‘are and ought to be the representers of the sence of our County’.15 In the divisive months leading up to the declaration of war in August 1642, however, it was no longer possible for any group to represent the views of the whole county. A parliamentarian counter-petition was, therefore, rapidly launched at the Maidstone quarter sessions in late April by the parliamentarian magistrate Thomas Blount, who delivered it to Parliament on 5 May. Blount was appointed as colonel to a Kent regiment at the start of the war and remained anti-royalist during the civil wars and Interregnum. He was appointed as one of the commissioners to try Charles I, but he did not participate in the trial.16 The newly discovered signatures on this petition, which are now in the parliamentary archives, were not examined by Everitt and have never previously been analysed. They will, therefore, be considered at greater length below. Blount’s petition did not claim to come from the whole of the county, but it used more inclusive language than did Dering’s to describe its subscribers. It was thus presented in the name of ‘many of the Gentry, Ministers, freeholders & other inhabitants of the County of Kent, the Citties of Canterbury, Rochester & the County of Canterbury, the Cinque Ports & their Members & other corporations w[i]thin the said County’.17

The different language used by the two groups of petitioners is of some significance. While Dering’s petition clung to the patriarchal idea that the small groups gathered at the assizes represented the opinions of the county, Blount’s petition was more individualistic. It was based on a wider constituency, while at the same time acknowledging that it represented the views of ‘many’ of the people of Kent and not all of them. It included the inhabitants of the towns, liberties and corporations, which traditionally were not a part of the administrative jurisdiction of the county. It might be objected that this was typical of parliament’s approach to county government, in which the committee system was used to overcome opposition from a variety of local interests. Yet these differences also alert us to the fact that, even before the committee system got underway in Kent, there were at least two competing views of how communal opinions should be formed and expressed. By early 1649 the radical grouping in the county calling for the trial of Charles I and the execution of the royalist leaders described themselves simply as ‘the well-affected in the county of Kent’, without any social distinctions, perhaps because no major gentry signed their petition. In all of the major petitions examined in this essay there is, however, a clearly expressed view that the county was the focus for the expression of the political and religious opinions of its inhabitants. For the petitioners, there was indeed a community of Kent, even though that community was divided in its opinions and allegiances.18

By widening Everitt’s definition of the county community to include the clergy, townsmen, freeholders and other inhabitants of Kent, it becomes possible to find evidence of all shades of political and religious opinion in the county during the civil wars. In particular, the existence of strong parliamentarian allegiances in the county demonstrates that the early acceptance of parliamentarian rule there was not achieved simply through force, as Everitt believed. Instead there was considerable support in Kent for the parliamentarian cause, which was often, but not always, associated with areas of long-standing nonconformity. A number of Wealden towns in west Kent, such as Cranbrook and Goudhurst, had puritan traditions which stretched back to Elizabeth’s reign. It is thus not surprising that at the beginning of December 1640 the inhabitants of the Kentish Weald promoted a ‘root and branch’ petition to parliament which demanded the abolition of episcopacy and was subscribed by 2,500 people in the county, since east Kent also had its share of nonconformist groups in towns such as Ashford, Dover and Sandwich.19 Ashford, Canterbury and Cranbrook, along with its surrounding parishes, all raised volunteer forces for parliament in 1642 even before war had broken out. Religious dissenters saw the conflict as a chance to achieve further Church reforms and the godly parliamentarian officer Sir William Springate described himself in his will, drawn up in May 1643 because of the ‘danger in these times’, as employed for ‘Christ and his Church’. He also raised a force of 800 men from Kent, who enlisted with him because, according to his wife, they too were puritans.20 Parliament later resorted to conscripting men from Kent, thus making it impossible to use their military service as a test of allegiance. In addition, the dominance of parliament made it difficult for the royalists to recruit men inside the county, similarly making it hard to assess the numbers who volunteered there to fight for the king. Nevertheless, 22 royalist colonels from Kent fought in the first civil war, 3 of whom died in the conflict.21

During the first civil war of 1642-6 Kent was not exposed to the movements of the main field armies, but there were two occasions when some of the population rebelled against parliamentarian hegemony in the county. In 1643 about 4,000-6,000 armed men set up three camps between Sevenoaks and Faversham. George Hornby has demonstrated that the rebels were not gentry-led, but were yeomen, husbandmen and craftsmen from the Upper Medway Valley around Tonbridge, the Wrotham Chartlands, Maidstone and Greenwich. Among their demands was a refusal to take the Vow and Covenant to support parliament against the king imposed in the wake of Waller’s plot in London. The rebels were dispersed by troops commanded by Colonel Richard Browne after a ‘hot fight’ at Tonbridge, where the parliamentarians were in the minority among the inhabitants.22 Four years later the Christmas riots at Canterbury saw a sustained revolt against parliamentarian rule in the city which preceded the outbreak of the second civil war in Kent and Essex. By the summer of 1648 11,000 royalists and disillusioned former supporters of parliament were in arms in the county. They occupied strategic strongholds along the coast including Dover Castle, but were overcome in early June at Maidstone and Canterbury ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Preface a Personal Memory of Alan Everitt

- Introduction the Impact of the County Community Hypothesis

- 1 Alan Everitt and The community of Kent revisited

- 2 A convenient fiction? The county community and county history in the 1650s

- 3 The cultural horizons of the seventeenth-century English gentry

- 4 Fashioning communities: the county in early modern Wales

- 5 The Restoration county community: a post-conflict culture

- Conclusion County Counsels: Some Concluding Remarks

- Select Bibliography

- Index