![]()

1 Metaform

Biology | mechanics | structure

Form, growth and process

In Britain after World War II, artistic engagement with biology took an increasingly mechanical turn. After a war that had seen British biologists and psychiatrists commissioned to engineering, code-breaking and logistics, a more holistic view of systems behaviour, from the organismic to the technological, gradually infiltrated every discipline.1 D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form remained a powerful influence for British artists, although its central thesis of treating biological form as process was also gaining new relevance and complexity in relation to theories of field and environment.2 In 1951, debates about the new biology were given a platform when Richard Hamilton’s exhibition Growth and Form and the accompanying symposium Aspects of Form took place at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, during the Festival of Britain. Also in the period 1945–55, several artists who were to contribute to the Basic Design movement in British art education were working at schools of art across London, but principally at the Central School of Arts and Crafts.3 This chapter will chart the debates about biological form and new technologies that preceded and informed the development of the Basic Design movement, outlining how the same ideas were incorporated into the art and design curriculum at King’s College. It will connect the manifestations of biological form-as-process in late British abstract art to the development of interactivity in the work of Ascott and his contemporaries.

In the immediate post-war years several British artists engaged with the mechanics of form, some of their number connecting their interest in form to cybernetics and the enclosing question of systems behaviour. Amongst their number were both Hamilton and Pasmore, who taught Roy Ascott at King’s College, the University of Durham in Newcastle from 1955 to 1959.4 The two artists might have had similar interests, but they often had opposing viewpoints; Hamilton was resolutely future-facing whilst Pasmore remained committed to abstraction for his whole career. Pasmore was at this time a well-respected and active artist, heading the Art Department, contributing to the development of national policy in art education, exhibiting and completing numerous commissions. Beyond this, he held great influence for his pupils, many of whom credit him as the most important figure in their education.5 Because Pasmore believed in intuitive process, his work was latterly and persistently misunderstood as lacking theoretical grounding.6 The two most contentious elements of Pasmore’s career were his conversion to abstraction from his previous delicate, impressionistic realism, and then, after a spell working with construction, his return to abstract painting at the precise moment the majority of artists had abandoned it. One of the tasks of this chapter is to pursue the philosophy of abstract form that Pasmore taught at King’s College, while considering the nature and extent of his influence upon Ascott and his contemporaries. While Hamilton has achieved greater fame and attracted far more research interest than Pasmore, his teaching at King’s College has not received the critical attention it deserves.7 Certainly, Hamilton’s pedagogy in the 1950s and 1960s was an extension of his practice, touching upon many of the same themes and ideas that he presented in his art and exhibitions of the same period. It is also evident that Hamilton’s consuming interest in – or even idolatry of – machines formed a discernibly influential element of the Basic Design curriculum. For this reason, this chapter seeks out the various points of intersection between biology, engineering and art pedagogy that drove students towards experiments in increasingly systematized and interactive abstract art. Moving on to Ascott’s training and early career, I then establish how this training contributed to Ascott’s conviction that ‘form has behaviour’, an idea that has endured in his practice for several decades.

On Growth and Form and the structure-process debate

While Hamilton was still a student, he developed an interest in both biological and engineered form and process. At the Slade, he met Nigel Henderson who first introduced him to On Growth and Form. The book quickly became an obsession and occupied much of his remaining time at the Slade. The Reaper prints were made directly prior to Hamilton’s larger project – the exhibition Growth and Form which he proposed and developed for the ICA. The exhibition explored the underlying philosophy of biological structuralism which Thompson had offered as an alternative to the prevalent, and in his view limiting, interest in evolution. It brought together cutting-edge imagery such as photomicrographs as well as scientific models and films, alongside abstract art with relevance to biological structure. None of this work was labelled, to allow for meditation upon the visual and formal qualities of the selected exhibits. In his initial proposal to Herbert Read in 1949, Hamilton pitched his ideas:

The initial stimulus for the proposed exhibition was provided by Thompson’s book On Growth and Form. The visual interest of this field, where biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics overlap was considered an excellent subject for presentation in purely visual terms. The laws of growth and form pertaining to the processes of nature are quite contrary to the processes of artistic creation. However complex the form (accepting Thompson’s hypothesis) it is the result of very precise physical laws; the complexities of art, on the other hand, are the products of involved psychological processes.8

This tentative description of the overlap of arts and sciences is an early formulation of Hamilton’s engagement with the processes described in On Growth and Form. In comparing the ‘involved psychological processes’ of art to the ‘precise physical laws’ of form, Hamilton linked the two with Thompson’s structured morphology.

Structure (Figure 1.1) was one of a series of prints Hamilton made at the Slade which explored the concepts he had gathered from D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson. He experimented with repetition of marks to create structured form and composition, relating to growth patterns in the natural world. The outcome has a network quality, the suggestion of lines connecting the decisive, incision-like crosses on the paper – it is a map of the series of decisions that led to the finished abstract image. This print gives a useful insight into Hamilton’s reductive approach to abstracting Thompson’s descriptions of growth patterns, each point of the composition darkly incised to highlight the underlying geometry of natural growth.

Figure 1.1 Richard Hamilton (1950) Structure. Liftground etching and aquatint on paper. 15 3/4 × 11 7/8 Tate Gallery

When Hamilton developed his ideas about On Growth and Form into a formal proposal, he articulated a rational structure for the exhibition, the subject headings of which were:

1 Time as a dimension of form

2 Forms of cells

3 Cell groupings

4 Skeleton structure

5 Related forms

6 Form and mechanical efficiency

7 The formal realization of pure mathematics9

This formed the basis for the ICA exhibition, and it offers an interesting illustration of the multidisciplinary approach upon which the ICA was conceived. It is not only the arts and sciences collaboration that made this exhibition an important event, but also that all the scientific disciplines are represented together, exploring the same themes of mathematical structure and growth in the natural world. Note that this linked set of subjects includes ‘form and mechanical efficiency’, a subject which relates both to Thompson’s entreaty to refer all form ‘to mechanism’ and also Sigfried Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command, in which he discusses how biological science had been altered by the mechanization of society.10 Hamilton himself made this link with Giedion explicit, when in his initial proposal for the ICA exhibition he wrote:

The most obvious benefits of the exhibition would be the influence it may have upon design trends. The general implications are very wide: S. Giedion in his study of mechanization says ‘The evolution from material and mechanistic conceptions must start from a new insight into the nature of matter and organisms’. The exhibition should also make its contribution in this direction.11

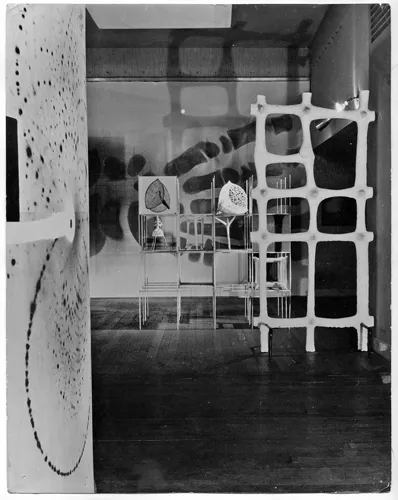

In the few existing installation shots of Growth and Form from 1951 (Figure 1.2), a soft-edged geometry of display is apparent.12 The abstract screen structure in the foreground is amorphous – reminiscent of cell structures, of bones and of rock formations. It was created by Hamilton as part of his exhibition design. Behind it, there are the open cubic frames that Hamilton used to display the objects, and on the walls, abstract painted forms with the same amorphous quality of the screen – like bones, rocks or drops of water. This fusion of interdisciplinary objects and abstract imagery was a strategy Hamilton would employ again in his later exhibitions for the ICA, including Man, Machine and Motion in 1955.

Figure 1.2 Installation view of Richard Hamilton’s exhibition Growth and Form (1951) ICA archive, Tate Gallery

The cubic display structures employed by Hamilton have as much interest as the exhibits themselves. Hamilton commented that:

Growth and Form seemed an ideal subject for another involvement of that time, exhibition design. By the turn of the century the ‘exhibition’ was b...