eBook - ePub

Play and the Artist’s Creative Process

The Work of Philip Guston and Eduardo Paolozzi

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Play and the Artist's Creative Process explores a continuity between childhood play and adult creativity. The volume examines how an understanding of play can shed new light on processes that recur in the work of Philip Guston and Eduardo Paolozzi. Both artists' distinctive engagement with popular culture is seen as connected to the play materials available in the landscapes of their individual childhoods. Animating or toying with material to produce the unforeseen outcome is explored as the central force at work in the artists' processes. By engaging with a range of play theories, the book shows how the artists' studio methods can be understood in terms of game strategies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Ageing Play

[T]his serious play, which we call art, can’t be stamped. I mean you have to keep learning how to play in new ways all the time.

Philip Guston, 19721

“Play” is a word one commonly hears as an artist or art student in a studio environment. It is usually used to denote the “light” and “carefree,” or a stage of experimentation before the serious work of art making begins to take shape. However, by engaging with a range of play theory, one can begin to reconnect with play as an immersive activity that involves risk-taking, tension, conflict and subversion. Play as serious fun. In this book, I explore a continuity between childhood play and adult creativity. I focus on how an understanding of play can shed light on some specific creative objectives and processes that recur in the work of Eduardo Paolozzi and Philip Guston. I begin by exploring a collection of childhood play activities that develop to inform the artists’ studio processes. Crucially, I will not suggest that the artists’ play processes are concerned with an attempt to recapture a sense of naivety; I move in the opposite direction, to explore what continues and evolves.

The artists’ play processes will be seen to provide tools with which to engage with the adult present. I will explore how these processes continued to be informed by the context within which they worked. While particular circumstances can be seen to have been conducive to play, the artists’ use of play methods and games strategies will also be understood to have provided the means with which to subvert the status quo. As an artist, I bring an understanding of studio methods and materials. I use this to focus on the artists’ studio processes. In examining the work of Eduardo Paolozzi and Philip Guston, this project does not explore performance art or socially engaged practice. While these forms may seem to be the logical territory for a study of art and play (and indeed there are already many excellent publications that explore these areas), here I focus instead on how an understanding of play can inform an approach to object and image making. My examination of these processes aims to be of use to artists, art historians, curators and creativity researchers, in addition to providing the viewer with an interactive role.

To some extent, both Guston and Paolozzi’s careers have invited categorisation and myth to grow around apparent decisive, dramatic leaps in style and form. For Guston, debate has revolved around the fact that his career seems to divide into three main periods, beginning with early success as a figurative painter, followed by critical acclaim as part of the New York School of Abstract Expressionists and concluding with a dramatic and legendary break back into figuration with his late “cartoon-like” works. For Paolozzi, The Independent Group, Pop Art and Surrealism have all continued to exist as markers that define any attempt to categorise an extraordinarily multi-faceted career. Guston and Paolozzi, then, may appear to be an unlikely pairing of artists. However, in moving beyond the geographical gap and art historical labels, one can identify shared objectives and processes and thus bring a new understanding to the artists’ individual working processes. I will examine both artists’ distinctive engagement with popular culture as connected to the play materials available in the landscapes of their individual childhoods. Animating or toying with material to produce an unforeseen outcome will be understood as the central force at work in these artists’ processes. It is here one discovers a continuity between childhood play and the artists’ adult creativity.

Throughout the book, I explore both artists’ resistance to finality. While Paolozzi is famously known as a collagist, we will see how the artist found it “upsetting” to stick things down2 and found ways to continually reanimate “the frozen picture.”3 In parallel, I examine how Guston consistently voiced the need to treat paint as a living substance. While creating his apparently abstract works, Guston described his forms as “living presences.”4 And while creating his late figurative work, the artist described his sense that he was creating “living things”5 that appeared to have a life of their own. This book will examine how Guston and Paolozzi’s materials and processes allowed the artists to refute the conclusion of the artworks to play repeatedly with the life of form. By placing the artists’ work within the messy mass of their studio material, the book seeks to continue to animate the works by placing them within an unfolding process. It is here the viewer can join the artists and play with the life of the work.

The Studio Landscape

Eduardo Paolozzi: “An Architecture From the Tools of a Child”6

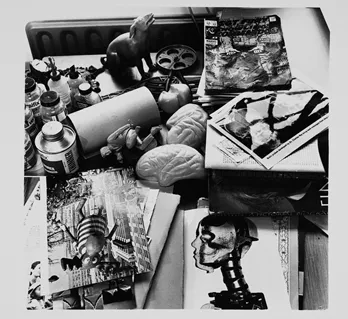

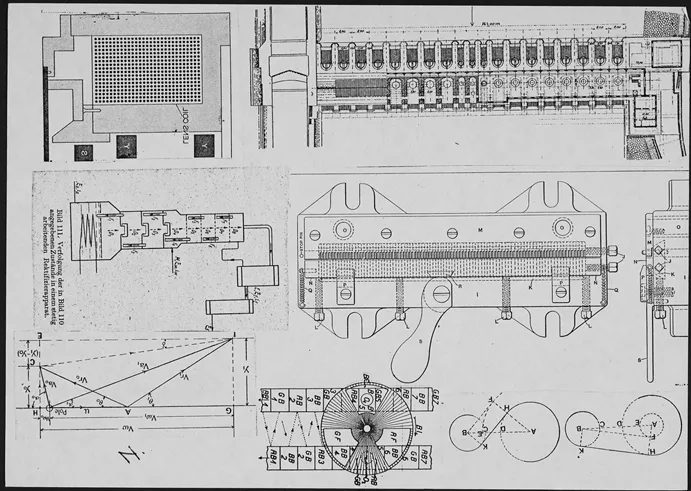

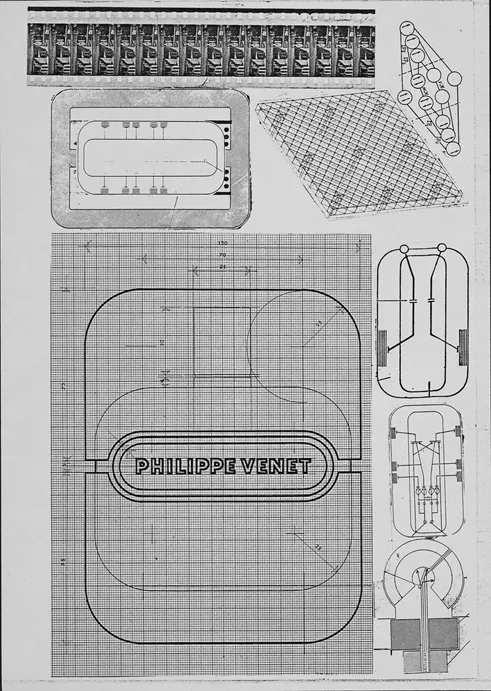

Eduardo Paolozzi was a lifelong collector and hoarder. Over the course of his career, a towering mass of material accumulated in his studio (Figure 1.1). Among the artist’s working models and cast elements were stacks of toys, books, broken machinery and printed ephemera (Figure 1.2). The artist’s personal collection of popular culture, donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum as the Krazy Kat Arkive, reaches into excess of 20,000 objects. The majority of Paolozzi’s printed ephemera has been left to The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Looking through the hundreds of folders of Paolozzi’s material held in the gallery’s archives is an overwhelming experience. In the vast mass, one encounters a dizzying array of material that includes loose receipts, empty envelopes, menus, advertising, concert programmes, technical diagrams (Figure 1.3), telephone sex cards, magazine cuttings of robots, a giant picture of a flea seen under a microscope, aerial views, images of bombsites, pictures of Mickey Mouse.… When looking through the collection, one initially has a tendency to search for relevance, to attempt to sort the material into hierarchies of importance, to search for categories and taxonomies. But the material continually seems to fight back. Over time, one begins to see the collection in terms of action. To understand Paolozzi’s processes, one has to approach all the material as equally important—the result of an activity that produced a landscape from which the work emerged.

Figure 1.1 Interior of one of Eduardo Paolozzi’s London studios, 1994 (View 10 of 21), Eduardo Paolozzi, National Galleries of Scotland. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Archive.

© Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2018.

Figure 1.2 Desk with printed matter and toys/toy brains. Eduardo Paolozzi’s studio at 107 Dovehouse Street, London, 1970. National Galleries of Scotland. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Archive.

© Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2018.

Figure 1.3 Eduardo Paolozzi Archive preliminary handlist: artwork, correspondence, papers, source material, newscuttings and printed ephemera, Eduardo Paolozzi, National Galleries of Scotland. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Archive.

© Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2018.

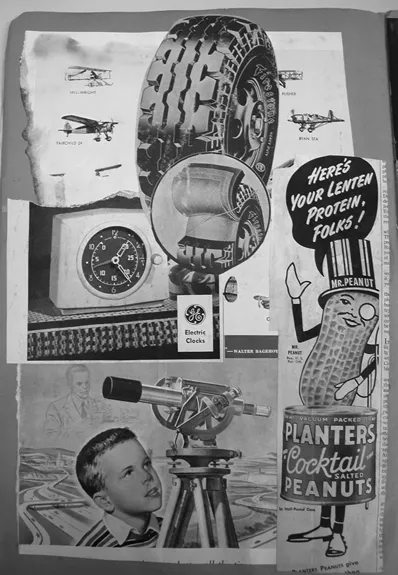

Throughout Paolozzi’s career, the collection of printed ephemera formed the basis of the artist’s collages, prints, mosaics, tapestries and films. One can see everything in the collection as held in a state of readiness, transformed from waste material to play material. Indeed, Paolozzi’s avid collecting was an activity that dated back to his childhood days; making scrapbooks was a practice he had continued from childhood through to adulthood (Figures 1.4 and 1.5). Reminiscing about his early years

Figure 1.4 Page of a scrapbook, 1947–52, Eduardo Paolozzi, Victoria and Albert Museum Archives, London.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2018.

Figure 1.5 Page of a scrapbook, 1960, Eduardo Paolozzi, Victoria and Albert Museum Archives, London.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London and Trustees of the Paolozzi Foundation, licensed by DACS 2018.

growing up in Edinburgh in the 1920s and 1930s, Paolozzi stated: “It is difficult to think of a time when cutting images out of magazines was not a daily event.”7

The literary critic Susan Stewart defines collecting as “a form of art as play.”8 In her publication On Longing, Stewart provides us with a necessary distinction between the souvenir and the collection with reference to time. For Stewart, the souvenir is commonly used as an aide to memory: “This childhood is not a childhood as lived; it is a childhood voluntarily remembered… manufactured from its material survivals.”9 By contrast, for Stewart the collection is not concerned with a focus on the past, nor is it an attempt to restore material to an origin; rather, time becomes simultaneous within the collection. To regard collecting as a play activity is to engage with the means by which assembling creates new contexts and new relationships between material. Using Stewart’s terms, we do not need to see Paolozzi’s continued collecting as a nostalgic act; rather, collecting can be seen as a continued play activity concerned with inventing changing, evolving relationships within assorted material. It is therefore necessary to see the items in Paolozzi’s collection not in isolation as a “diagram” or “advert” but as part of a process. It was the mess—the open relationships between the items—that was so important to their usefulness. The mass of material was continually on the move within the artist’s studio. In preparatory notes for a lecture, Paolozzi himself described how this shifting landscape was the generative source from which all his work sprang:

In the preparations for this talk I had to move endlessly a lot of material around my studio projects old and new, plaster, plywood, cardboard pieces, discoveries and long forgotten items. The room resembles in its chaos the various dramas that go into making a drawing or sculpture. What is that moment when something torn out of “Time” magazine, date unknown, reveals itself in view of others… meaning subject to interpolation or image subject to translation redefines its identity.—Transfor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Colour Plates

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Ageing Play

- 2 Kits and Building Blocks

- 3 Creative Battles

- 4 Eduardo Paolozzi’s Playgrounds: Contradictions in Art and Play

- 5 Shuffle/Spin/Stack: Emergent Narrative

- 6 Absurd Processes

- Concluding Remarks

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Play and the Artist’s Creative Process by Elly Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.