![]()

CHAPTER 1

What Is Art?

What is art? Three simple words – a very tricky question.1

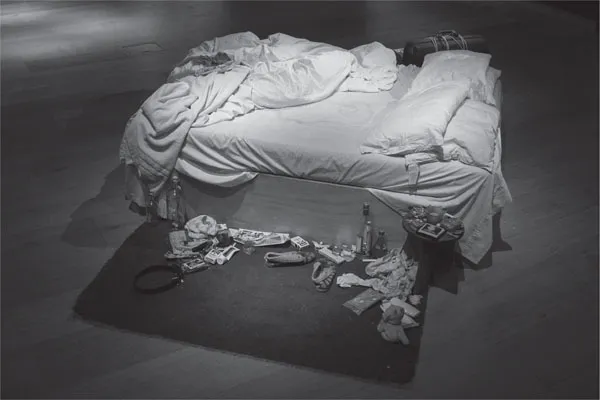

For example, the best-selling art book of all time, The Story of Art by E. H. Gombrich, begins with the statement: ‘There is really no such thing as Art. There are only artists.’2 This, or something like it, is a popular view, particularly among artists; indeed, I often heard Tracey Emin, faced with the challenge that her work My Bed was not really art, reply that ‘art is what artists do’ or perhaps that ‘art is what artists say it is’, and that therefore, since she, an artist, had declared My Bed to be a work of art, it must be so. There is much more to be said about this view, and various attempts have been made to justify or elaborate it. But as it stands, it contains a very obvious logical problem: If art is what artists do (or say it is), what makes someone an artist? You would think, would you not, that an artist was someone who made art? But then Gombrich’s or Emin’s answer turns out to be both circular and empty. And this kind of problem keeps recurring whenever we try to answer the ‘What is art?’ question.

In fact, in order even to attempt a serious answer to ‘What is art?’, we have to answer a raft of prior questions, such as: By ‘art’, do we mean visual art, whatever that may be (painting, sculpture, etching, drawing, installations, video art, film, performance art), or do we mean art in the more general sense (novels, plays, poetry, music, opera, pottery, dance, photography, film)? Or do we mean the word ‘art’ (the art of cookery, the art of motorcycle maintenance, the ‘noble art’ of boxing, or Art, short for Arthur)? Do we mean art everywhere and for all time, throughout human history, from before the Lascaux cave paintings to Ai Weiwei today? Or do we mean art over a specific period of time in a specific society? By ‘What is art?’, do we mean, ‘What is the definition of art?’ Are we trying to define a word, or a thing – or a set of things? What would it mean to define art? What do we mean by a definition? What makes us think art can be defined? Is it desirable that it should be? These questions fold into each other like opposing mirrors, seemingly ad infinitum (or maybe ad nauseam). So, given that the question is so tricky, why bother with it at all?

Tracey Emin, My Bed (1999)

Well, to deal with the last question first, it might seem a good idea, in a book about art, to know what we are dealing with. Moreover, the question is out there; a quite disproportionate amount of media coverage of modern visual art proceeds, and has proceeded for quite a long time, under the rubric ‘But is it art?’. It was hearing this challenge repeatedly put to work of Christo, Hirst, Whiteread, Emin and others (as it has previously been put to that of Picasso, Brâncuși, Pollock, Warhol, Andre, etc.) and realising that the people who put it had no criteria by which to judge it other than whether it resembles what they were used to thinking of as art (paintings by Vermeer or Constable or Monet or whoever), that first led me to try to investigate it. Then – and this is the most important reason for addressing it here – I found, in the process of the investigation, that it pointed to a number of significant conclusions (truths, I believe), not only about art itself but also about the nature of human life and labour in class-divided societies – capitalist societies especially. Furthermore, I found that these conclusions have political implications.

The question ‘What is art?’ as I am posing it here is a call for a definition. A definition, according to my copy of the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, can be either a statement ‘of the precise nature of a thing’ or a statement of ‘the meaning of a word’.3 This is very unhelpful; how can one state the precise nature of anything, let alone a category like ‘art’ that necessarily involves millions of different ‘things’? Moreover, the word ‘art’, as I noted above, has many different meanings. More useful, perhaps, is the same work’s first entry for ‘define’ – ‘mark out limits of’ – and for ‘definite’ – ‘having exact limits; determinate, distinct’. Anyway, what I am seeking to do is to define art, in the sense of establishing criteria for distinguishing works of art from other things which are not works of art. This is so as to be able to answer questions such as ‘Is Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII4 or Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square on White a work of art?’ or ‘Is the rhyme in my birthday card a work of art?’ or a song by One Direction or a solo by Louis Armstrong and so on, without the answer depending on whether I happen to like or approve of the particular work.5

For various reasons, definitions are always a problem. Dictionary definitions, like those cited above, are generally of little use when trying to establish the meaning of complex and disputed concepts, things or events. A dictionary definition of feudalism might be useful if you have never come across the term, but it won’t help much in deciding whether or not Russia in 1914 or Britain in 1642 was feudal, any more than a dictionary definition of socialism (which dictionary, whose definition?) will settle whether Russia in 1936 was socialist. Moreover, all definitions, even the most apparently precise, have a tendency to fray at the edges. This is because definitions aim to distinguish between things (or concepts) – a very necessary task for human beings generally – but in reality ‘things’ are processes, processes of coming into being and passing out of being, and therefore not, in the end, separate and distinct entities. And the same is true of the concepts we develop in order to try, as we must, to pin things down. ‘The concept’, says Leon Trotsky in his Philosophical Notebooks, ‘is not a closed circle, but a loop, one end of which moves into the past, the other – into the future. If you pull at its end you can undo the loop, but you can also knot it.’6 So the definition of art that I propose is bound to be, in a sense, imperfect, and there are bound to be problematic transitional cases between art and nonart. This, as we shall see, is an important qualification. But the fact that day merges into night through twilight does not mean we should dispense with the concepts of day and night.

Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII (1966)

Then there is the fact that in order to establish a ‘definition’ of something, in the sense that I intend – namely, a statement of its limits or defining criteria – you first have to have a rough idea of what it is you are trying to define. What I am attempting to define here is not just ‘visual art’, but art in the general sense listed above (painting, music, literature, cinema, pottery, etc.) as it is commonly spoken of; but not all uses of the word ‘art’. So if it turns out that boxing does not meet my criteria (and it doesn’t), the fact that it is sometimes referred to as ‘the noble art of self-defence’ is not a problem for my argument. But if it turns out that T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land or a composition by John Coltrane or a novel by James Joyce doesn’t meet my criteria, that would be a serious problem.

Secondarily, my aim is to define art for what I will call the capitalist or bourgeois era: that is, roughly from the beginning of the Renaissance (in Europe) through to the global present. It is clear that something we would now call art has existed since at least the Upper Paleolithic period (e.g., cave paintings dating back over thirty-five thousand years) and that every human society or culture of which we have evidence was engaged in activities (painting walls, making music, dancing, storytelling, etc.) we would now be likely to call art. But it is also clear that the modern use of the word ‘art’ to denote a specific sphere of activities and objects, comprising painting, music, literature and so on, distinct from other nonartistic activities and objects, did not apply to many or most of those periods or cultures. Now, it may well be that much of what I have to say will apply to some extent to art-type activities of the distant past and from many cultures – to the cave paintings of Lascaux and Chauvet, to Homer, to Haiku poetry and Benin bronzes – but I am deliberately limiting my attempt to provide a definition to the capitalist era, and if it can be shown that it doesn’t work for Aztec sculpture or the architecture of ancient Zimbabwe, then so be it.

This is partly because I don’t wish to bite off more than I can chew, or to claim a universality or timelessness for my views that is likely to prove unsustainable. But there is a more important point involved here: the concept of art, as it is widely used today and as I want to define it, did not exist before the bourgeois era. The word existed, but its meaning, and thus its use, was fundamentally different. The word ‘art’ comes from the Latin ars/artis, which in turn is a translation from the Greek techne, which simply meant skill. The modern use of art, as in ‘the art of cookery’, which I have referred to above, is a residue of this old meaning. As Władysław Tatarkiewicz writes in a very useful article on the history of the concept of art:

[‘Techne’] in Greece – ‘ars’ in Rome and in the Middle Ages, even as late as the beginnings of the modern era, in the age of the Renaissance – meant skill, namely the skill required to make an object, a house, a statue, a ship, a bedstead, a pot, an article of clothing, and moreover also the skill required to command an army, to measure a field, to sway an audience….

Art, understood as it was in antiquity and in the Middle Ages, thus had a considerably broader scope than it does today…. Consequently not only painting or tailoring could be regarded as art, but so also could grammar and logic – precisely as sets of rules, as kinds of expertise. Thus at one time art possessed a broader scope: broader by the handicrafts and by at least part of the sciences.7

There was also a distinction made between the liberal (liberated) and the vulgar or mechanical arts. The former involved only mental labour, whereas the latter required also physical effort. The liberal arts were considered to be greatly superior to the common or mechanical arts, and painting and sculpture were considered lowly activities among the mechanical arts.

During the Middle Ages the liberal arts were considered to be grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music – seven in number. For the sake of symmetry, attempts were made to reduce the numerous mechanical arts to seven categories, and in the process painting and sculpture (considered of little importance) often fell off the lists altogether. Poetry was ‘regarded as a kind of philosophy or prophecy and not as art’8 and failed to make any of the lists.

It was during the Renaissance that the modern concept of art began to emerge. The Marxist art historian Arnold Hauser identifies Michelangelo as a key figure in this process and argues that ‘[t]he fundamentally new element in the Renaissance conception of art is the discovery of the concept of genius, and the idea that the work of art is the creation of an autocratic personality, that this personality transcends tradition, theory and rules.’9

And it was during the second half of the eighteenth century and the nineteenth century that this modern concept was consolidated and became hegemonic. Tatarkiewicz sums up the process as follows:

The history of the concept [of art] in Europe has thus lasted for 25 centuries and falls grosso modo into two periods, each of which entertained a different concept of art. The first period – that of the ancient concept – was very long, stretching from the 5th century BCE to the 16th ad. Over these long centuries art was construed as production in accordance with rules…. The years 1500–1750 were years of transition: the erstwhile concept, though it had lost its earlier position, nevertheless still persisted, while the new one was already being prepared. At length, around 1750, the old concept yielded place to the modern one.10

It is this ‘modern’ concept that I am concerned with trying to analyse, and while Tatarkiewicz does not mention this, a Marxist cannot fail to note that his periodisation corresponds, more or less exactly, to the emergence and development of capitalism. It is worth noting here that the first public art galleries and museums emerged in the eighteenth century and that the world’s largest and historically most important art museum, the Louvre, was established in 1793 as a direct result of the French Revolution.

Moreover, I believe that my analysis of the nature of art will help to explain why ‘art’ in its modern sense and usage emerged as a distinct category and sphere in the capitalist era.

I said earlier that it is necessary to establish whether one is defining a word, a thing or a set of things. Since Wittgenstein, we have known that the meaning of words is determined in and by their use, and that the same word (i.e., a sound or set of letters) can have different meanings when used in different ways and different contexts. I can play a tune, play football and go to a play. I can sit in a chair, or chair a meeting, or hold the chair of philosophy in a university. But it does not follow from this, as some post-structuralists have claimed, that there is no necessary link or connection between words or concepts and the ‘real’ or material world. Rather, I believe, with Marx, that that connection is established in human practice. ‘All social life is essentially practical,’ he writes in his Theses on Feuerbach. ‘All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the comprehension of this practice.’11 And I believe that the word ‘art’, in the way in which it has been used for several centuries to distinguish certain activities and objects from nonart activities and objects, does correspond to or represent (broadly) a real distinction which exists ‘out there’ in social practice. My aim in attempting to answer the ‘What is art?’ question is to try to identify the basis of that distinction.

This book will focus mainly on visual art, but I think the example of writing and literature helps clarify the distinction I’m talking about. The society we live in is full of writing: there are handwritten notes and letters, typed letters, emails, tweets and Facebook posts; there are business letters, bills and invoices, technical instructions on products, signs and notices at airports and train stations, adverts, newspaper articles, scientific papers and so on, endlessly. Out of this immense amount of writing, a tiny fraction of it gets to be considered, by anyone, to be art. On what basis? You could answer that it is mainly poetry, short stories and novels that receive such consideration, but, setting aside the difficulty of defining poetry, short stories and novels, this is not an adequate answer, because it leaves out (some) essays, (some) drama, (some) film scripts, (some) radio scripts, (some) written music and so on. Nor can the answer be given in terms of the persons – “art writing is writing produced by artistic writers” – since all ‘art’ writers (Yeats, Eliot, Neruda, Dostoyevsky, Roy, Pinter, whoever) did lots of writing which neither they nor anyone else ever suggested was art.

One further preparatory point: I know from considerable experience that when I try to define the concept of art, many people think I mean good or great art. They think if I am arguing that Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided (his cut-up cows) is definitely a work of art, then this can be answered by saying they don’t like it or don’t think it is any good. This misunderstands my point. There has always been any amount of mediocre or downright poor art (or poetry, or music, etc.) – the art galleries, libraries and music shops are full of it – but it is still art. In the same way, there is Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi, and then there are the lads kicking a ball around in my local park, but they are all playing football, jus...