eBook - ePub

Feminist Subjectivities in Fiber Art and Craft

Shadows of Affect

- 170 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Feminist Subjectivities in Fiber Art and Craft

Shadows of Affect

About this book

This book interprets the fiber art and craft-inspired sculpture by eight US and Latin American women artists whose works incite embodied affective experience. Grounded in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, John Corso-Esquivel posits craft as a material act of intuition. The book provocatively asserts that fiber art—long disparaged in the wake of the high–low dichotomy of late Modernism—is, in fact, well-positioned to lead art at the vanguard of affect theory and twenty-first-century feminist subjectivities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Feminist Subjectivities in Fiber Art and Craft by John Corso Esquivel,John Corso-Esquivel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Stranger Twins

“Inside and Outside at the Same Time”

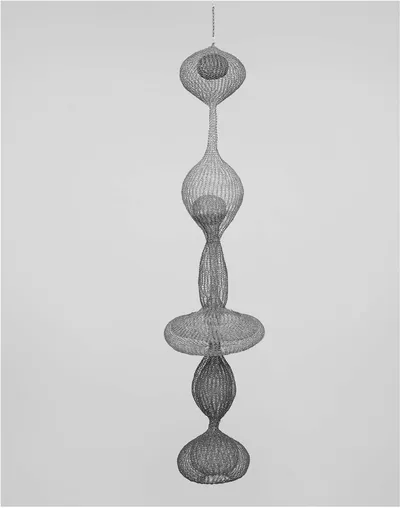

In recent years, the art world has paid closer attention to Ruth Asawa’s accomplishments. A star pupil of the experimental Black Mountain College, Asawa has inspired a generation of artists, and her public art continues to delight children and urban pedestrians. Only lately have dominant art institutions begun to position her sculpture prominently within their permanent collections.1 Because of this institutional attention, I was recently able to see two Asawa works not previously on view, one hanging wire sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the other at the Whitney Museum. The installation at the Whitney Museum offered an intimate experience with Asawa’s suspended woven sculpture. Asawa’s Untitled (S. 270) (1955/1958)2 hangs dramatically at the end of an open elevator corridor in a place of prominence. The 64-inch tall piece hovers above a short plinth-like pedestal about six inches high. The sculpture hangs relatively close to a translucent window shade. Light softly pours into the area, causing subtle shadows to appear. Spotlights aimed directly at the sculpture pass beams through it, leaving soft, vaguely overlapping shadows on the plinth below.

At first glance, Untitled (S.270) appears as a simple, axially organized silhouette, but as you approach the sculpture, its deceptive complexity begins to surface. Six stacked translucent mesh lobes rise like a totem, a turned wooden furniture leg, or three hourglasses arranged one upon the other. The sculpture itself resembles a shadow since the coarse weave and reflective materials dapple light much like fields of intercepted light that overlap. Like shadows, these globular meshes interpenetrate with the spatial organization that seems to defy our expectations of discreetly organized volumes.

A closer look reveals silhouettes within silhouettes, orbs within hourglass figures. These interlaced surfaces trade places and interior shapes become exterior surfaces. That is, interior forms escape the internal domain at specific intervals to become outer manifolds themselves. For instance, a layer of looped brass wire starts as an outside layer at the tip of the sculpture. It pinches into a tight tube, then flutes outward again only to contract into another tube that flips inward, becoming an interior membrane. In this way, Asawa offers visual oscillations to disorient directionality as efficiently as a Möbius strip.

The late Los Angeles curator Karin Higa brought together several interview sources to show the deliberateness with which Asawa obliterated interior—exterior oppositions. In a catalogue essay entitled “Inside and Outside at the Same Time,” Higa cites Asawa, who said, “What I was excited by was I could make a shape that was inside and outside at the same time.”3 Higa continues quoting the artist: “You could create something . . . that just continuously reverses itself.”4 Noting that “an Asawa [looped] wire sculpture has no front or back or inside or outside,” Higa describes the binary as a “duality.”5 Such a duality indeed does not constitute a dualism, separating the mind from the body as in Descartes’ formulation. Instead, the duality that Higa speaks of should be understood not as a description of the binary nature of the sculpture so much as different modes of perceiving the artwork. The continuous reversal Asawa describes is a product of a continually shifting phenomenology as much as a description of the formal qualities of the rippling looped-wire work.

Figure 1.1 Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S. 270, Hanging Six-Lobed Complex Interlocking Continuous Form within a Form with Two Interior Spheres), 1955/1958. Hanging sculpture, brass and steel wire, 63 7/8 × 15 × 15 in. (162.2 × 38.1 × 38.1 cm).

For Higa, this duality contains more than the coexistence of directional binaries like interior and exterior: she contends that “the material contains simultaneously its past and future states.”6 That is, any stitch in the sculpture lies contiguously with its past—the stitches that preceded it—and its future—the stitches that will succeed it. Higa does not use the term “virtuality” to describe this, but Deleuze’s sense of the term seems apt. For Deleuze, the virtual refers to real possibilities that have not yet been actualized but are, nonetheless, real. Higa sees the case of the coexistence of these “various states” in an Asawa sculpture as a metaphor for her Japanese American heritage.7 That is, the fluidity of the sculpture, “moving from one state to another while remaining essentially itself,” parallels the displacement that was catalyzed by Asawa’s Japanese American experience. This displacement began with her parents’ immigration and later continued with the forced internment Asawa and her family experienced when the US government incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II. (As is evident in a letter she wrote to her future husband, Albert Lanier, Asawa seems to identify with a much more extensive sense of nomadism, saying, “I no longer identify myself as Japanese or American, but a ‘citizen of the universe.’”)8

I agree with Higa’s assessment that Asawa’s shifting sculpture parallels her biographical nomadism, though I would add that Asawa intently focused embodied awareness and movement throughout her life. More precisely, Asawa’s interest in a live phenomenology tore down the border between aesthetic art experience framed by institutions and the remainder of life. The fluidity between inside—outside and the virtuality of future and past within the present, I argue, attests to Asawa’s interest in a phenomenology that looks to “flips” of variables. That is, this is a phenomenology of difference that resembles the radical empiricism of Deleuze.

This chapter investigates two cases in which the artist approaches duality as a quest to know the self as other. From her early days at Black Mountain College, Asawa developed prolific explorations into the figure of the double to access a direct, empirical experience of art that breaks down the border between self and other. This trans-subjective experience does not constitute a deconstructive act. By invoking philosopher Alenka Zupančič’s “theory of the two,” which she develops in her 2003 book The Shortest Shadow, I interpret Asawa’s use of doubles—particularly the figure of the shadow—as an attempt to know the self through estrangement rather than identification. Similarly, artist Sheila Pepe uses the image of the shadow in a series she calls the Doppelgängers. Pepe’s use of objects and their twin shadows also emphasizes an estrangement from the self, established through its shadow image. Both of these artists concentrate on doubling as an act that creates relationships through alterity. Moreover, this act of doubling through the shadow precedes and makes way for the Deleuzian ontology of multiplicity. The shadow opens up space and social orientations rooted in an affective experience of otherness, which inspires mutual care and shared reverence.

Shadow Dolls

Sheila Pepe and Ruth Asawa were born 23 years apart and on opposite coasts of the United States. They each followed a circuitous path before developing individualistic methods of constructing suspended sculptures. Each artist contended with complex dominant social norms and their respective American art scenes, scenes that privileged (and continue to privilege) masculinist, monumental sculpture. Pepe initiated one of her earliest artistic challenges to the paradigms of modern sculpture as an object-based performance featuring dolls during her time living in western Massachusetts. She writes about the first dolls, which grew out of her undergraduate art studies in clay and ceramics: “from Boston Western [Massachusetts] they changed from ‘sculpture’ to dolls—the doll project was my investigation of this thing called [‘doll’]—a blatant surrogate for self as child, a blatant [recovery] device during therapy that was also sexualized [through] the surrogacy.” Pepe’s early dolls were reductive, schematic forms reminiscent of naïve early American dolls removed of their clothing. Calling the interactive performance “The Doll Project,” Pepe began to send one white doll to female friends in the area as well as friends and family in Troy, New York, and Boston.9 She asked participants to take photographs of themselves with the doll and write on their experiences.10 Pepe compiled these documents into a book. The project shows an early interest in the figure of the double, a psychoanalytically charged figure extensively discussed by Otto Rank.

In The Double: A Psychoanalytic Study, Otto Rank writes on a variety of figures directly applicable to “The Doll Project.” In the book’s first case study, Rank examines the double in the early film, The Student of Prague (1913, remade 1926), a silent film in which a handsome student, Balduin, makes a Faustian deal to offer the antagonist, Scapinelli, anything in his impoverished room in exchange for wealth to woo his aristocratic love interest. Scapinelli, Rank writes, “looks inquisitively about the room, apparently finding nothing that will suit him, until he finally points to Balduin’s mirrorimage (sic)” in a large mirror.11 Balduin agrees to what he believes to be a joke, until, Rank describes, “he is numbed with astonishment when he sees his alter ego detach itself from the mirror and follow the old man through the door and out upon the street.”12 Wherever the now well-compensated protagonist goes, it seems, his mirror double hauntingly follows. The film climaxes when Balduin attempts to shoot his mirror image, only to kill himself simultaneously. Rank offers a psychoanalytic interpretation of the scene that establishes the role of the double as an uncanny allegorical representative of the protagonist’s past deeds.13 He writes, “The ‘basic idea’ is supposed to be that a person’s past inescapably clings to him and that it becomes his fate as soon as he tries to get rid of it.”14

In Pepe’s performance, the do...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Stranger Twins

- 2 On Craft and Repetition

- 3 Down to the Wire

- 4 Subjectivities Before Subjects

- 5 Matrixial Shadows

- Index