eBook - ePub

Visual Culture in the Northern British Archipelago

Imagining Islands

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Visual Culture in the Northern British Archipelago

Imagining Islands

About this book

This edited collection, including contributors from the disciplines of art history, film studies, cultural geography and cultural anthropology, explores ways in which islands in the north of England and Scotland have provided space for a variety of visual-cultural practices and forms of creative expression which have informed our understanding of the world. Simultaneously, the chapters reflect upon the importance of these islands as a space in which, and with which, to contemplate the pressures and the possibilities within contemporary society. This book makes a timely and original contribution to the developing field of island studies, and will be of interest to scholars studying issues of place, community and the peripheries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Visual Culture in the Northern British Archipelago by Ysanne Holt,David Martin-Jones,Owain Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & European Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Islandness and Visual Culture between the Wars

In Terence Egan Bishop’s The Western Isles (1941) produced for the British Council’s ‘Films of Britain’, the narrator speaks of the Gaelic residents of the Hebridean island of Harris, their ancient speech and song and their time-honoured customs. Having fought the battle of the Atlantic for centuries, now in wartime they face a new battle. With a crofter’s son missing from his torpedoed ship – an actual event – ‘the women of the western isles wait, work and pray for their men who fight on the sea they know so well’. The film conflates islanders’ character, their stoic endurance, with the rugged, harsh environment they inhabit, even as here in technicolor. This conflation was very familiar by the later 1930s across countless visual images and forms of narrative, and doubtless expected to resonate with a wider national spirit of hardy determination required in wartime. One noted respondent, however, reacted negatively. Brendan Bracken, Director of the Ministry of Information, condemned the film for implicitly confirming Goebbel’s claim that the British were ‘fighting the war to perpetuate a way of living long since outmoded’ and that they had ‘lost the intellectual, moral and industrial lead which they once held’ (British Council Film: The Western Isles).

This chapter considers the developing context throughout the interwar period both for the film itself, and for Bracken’s reaction, and the variety of ways in which islands and notions of ‘islandness’ were practised through repeated and emerging forms of representation, discourse and behaviours. The examples discussed underline the extent to which, in active relation to shifting social experience and national imperatives, interwar cultural representations variously uphold, resist and dismantle reductive framing devices of the centre and periphery, the contemporary, forward-facing mainland and the archaic, backward-glancing island. Focus on islands in this period seems readily to lead to questions of the coherence of national identity and social structure, despite the actual messiness, change and conflict in these locations. The purported features of ‘islandness’ here appear almost as proxies for problems afflicting the national body politic in general.

Contemporary accounts of mid–1930s northern Britain typically underline the social and economic plight of regions devastated through the decline of heavy industry and agricultural depression. Vast stretches of the industrial north of England and the central belt of Scotland were perceived, most famously by J.B. Priestley (English Journey, 1934) and Edwin Muir (Scottish Journey, 1935) as desperate sites of degradation and decay. My focus, in relation to this broader conceptualization of north, is on the developing identities of island locations beginning with the Isle of Man off the north-west Cumbrian coast, islands of the Scottish Inner and Outer Hebrides, the northernmost isles of Orkney and Shetland, as well as the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and the Farnes off the east coast of north Northumberland.

Each of these sites experienced internal pressures throughout this period; heavy losses to small populations through service in the First World War, continual processes of emigration, the impact of absentee landlords in the Scottish context in particular and, in all cases, the hardship or decline of crofter or fishing communities. Nevertheless, these islands were constantly implicated in wider interwar imaginings as sites not just of retreat, but often of renewal and reassuring notions of community, and in some cases where the possibility of ideal behaviours or modes of existence might occur. These were all of course inflected by personal, social or political motivations, insider and outsider perspectives, and in instances, concepts of regionalism, nationalism and internationalism as they re-shape across the period. Amid each of the examples here concerns emerge for the preservation of tangible and intangible forms of heritage, the nature of identities: rooted or mobile, and matters of social and cultural distinction.

The chapter is especially concerned with the role of diverse and proliferating forms of visual culture. As such it departs from discrete studies of painting, print, photography, or film, for a focus on the relative importance of and relations between these forms in their address to particular groups, markets and audiences. The interwar of course is an especially fertile period for studies of the broader field of visual culture seeing, for instance, advances in colour lithography for print and poster reproduction, advances in camera design, democratizing access to and uses of photography, the development of documentary film, the growing popularity of amateur filmmaking and ever-widening access to cinema. The intense and at times competing forms of attention that islands were prone to, the overlayering or sedimentation of cultural representations of, and within, geographically bounded island sites, makes them especially valuable for the study of this field of images and visual technologies.

In continuation of familiar wider tropes of nineteenth-century European cultural tourism, islands to the north were frequently valued through this period for their apparent unchangeability and sense of permanence. Such sentiments were experienced acutely in the immediate aftermath of the First War, and with distinct implications for island communities and for those who visited or engaged with them in different ways. For visitors and those who imagined from afar, notions of distance and isolation are key, with both deriving from a perceived sense of disconnected and timeless spaces at the far edges, the extreme margins of the larger island of Britain. Here however, as elsewhere in this volume, ‘islandness’ is a relational term. The island examples considered vary in size, accessibility, distance, autonomy from and dependence on mainlands with, of course, Orkney and Shetland naming their own largest islands as Mainland. The negotiation of that island ‘boundedness’ and contrasting connectivity to other islands, to the UK mainland and beyond, are vital matters in the decades between the two world wars and play out across the discussion that follows.

Within these contexts two particular interwar literary voices are important: Louis MacNeice and Hugh MacDiarmid, both of whose relation to visual-cultural impulses are significant. For MacNeice ‘An island means isolation; the words are the same’ (1938, 8). For MacDiarmid, islands are ‘removed from the megalopitan madness’ (1939, x). They can be sites of exile or, following H.G. Wells, enable ‘human experiment unhampered by society’, and in a period of transatlantic economic depression, he cites the American essayist Katherine Fullerton Gerould: ‘When the plight of the planet becomes desperate, people usually begin to babble about islands’ (5).

Those claims though might be made of islands anywhere. In this specific context, Louis MacNeice’s 1937 tour of the Hebrides followed his and W.H. Auden’s Letters from Iceland at a time of what Anthony Blunt termed his ‘mania for going North’ (MacNeice, 1938, 22). For this Belfast-born Irish Protestant, however, whose father hailed from the island of Omey off the Galway coast, to travel to the Hebrides was to go West as well as North: ‘I hoped to find them like the West of Ireland – a wild landscape and a genial people’ (1938, 22–23). It was an identification others of the period had noted. Seton Gordon’s Islands of the West observed of Connemara that this ‘primitive part of Ireland’ recalls South Uist and Harris, but poorer, with men in rags who were friendly but seemingly ‘haunted by their past’ (1933, 136). The particularity of MacNeice’s desire will be discussed, but it is worth noting here that his comment also refers us back to significant pre-First World War tendencies in visual culture.

In that period Slade-trained painters such as Augustus John and Henry Lamb travelled to the Celtic peripheries of Brittany, Cornwall and the West of Ireland in search of what they perceived to be timeless ideal sites and ‘promised lands’. Distance was crucial and the ‘going to’ and ‘being in’ such chosen locations at the edges of the land allowed for much meditation on racial and national origins. Their aesthetic and cultural geographies provided a counter to vulgar modernity. In indeterminate, elemental settings, painted landscapes were reduced to bare bones, and the artist, here John, was a seeker after places ‘more stable and beautiful and primitive where one is bound not to be in a hurry’ (Holroyd, 1997, 305). And all of these individuals, inter-connected through social and cultural networks: Augustus John, John Millington Synge, Arthur Symons, and W.B Yeats (a crucial figure for MacNeice), triangulate European capitals and these coastal, Celtic regions which, in the end are almost interchangeable in the qualities they are seen to possess. In such a spirit Henry Lamb on Gola Island off the coast of Donegal, follows Synge in the Aran Islands off Galway Bay in translating individual peasant women, their shawls shielding them from the Atlantic gales, into robust and sturdy types via essential rhythmic and decorative forms. In Ireland of course islands of the West played a crucial role within the strands of cultural and political nationalism resulting in the formation of the Irish Free State in 1921 and the Republic of Ireland in 1937, but the broad tendency is repeated, as we will see, across particular visual and literary interwar imaginings of Scottish islands and their inhabitants.

Islands to the West: The Isle of Man

As this volume underlines, islands have forever existed within an inter-connected web of national and international networks exemplified by the ancient spread of Celtic Christianity from the West of Ireland, to the Inner Hebridean island of Iona, to Lindisfarne off the Northumbrian coast. Nineteenth-century antiquarian influence persists in developing preservationist discourses and concern, for example, over the steady decline of native languages. Those connections between land, language and cultural traditions were widely understood, and just as Cecil Sharp collected folk songs in England from the early 1900s, so John Lorne Campbell and Margaret Fay Shaw recorded Gaelic folklore and speech patterns from their base on the Hebridean island of Canna in the 1930s. Archival practices served to anchor the western isles and ‘islandness’ within ancient rooted pasts, if with international origins.

Preservationist preoccupations emerged early in the Isle of Man, a British dependency in the Irish Sea but once claimed by Scandinavia as well as by Scotland and England. The late nineteenth-century focus for antiquarians was Manx-Gaelic, in decline following steady emigration from the island’s inland glens and villages (Maddrell, 2002, 215–218). And while, for example, Pathé newsreels from 1920 onwards documented the continuation of the old Manx customs and language still in evidence at ritual events such as the opening of the Tynwald, modern circumstances and communications, especially the advent of radio and cinema, were widely cited as cause for the diminishing use of the native tongue. Both forms celebrate traditions for the benefit of wider audiences, but at the same time contribute to their demise.

Man’s preservationist was Sophia Morrison who had collected local fairy tales and established the ‘Peel Players’, a Manx-English dialect theatre on the model of W.B Yeats and Lady Gregory’s Abbey Theatre in Dublin (Faragher in Belcham, 2000, 336). With the same impulse to retain cultural heritage, the island’s Manx Museum was opened in 1922, focused on the importance of designer Archibald Knox (who died in 1933). Knox had contributed to and celebrated the island’s celtic legacy in its visual and material culture. His Guild of Design and Craft was regularly reported upon in The Studio Magazine, which brought the island’s cultural traditions to the attention of aesthetically cultivated national and international markets.

A key island issue was the maintenance of a Manx-British identity, and several incomer artists contributed to this. One, William Hoggatt, designed stained glass windows in the Manx Museum for the T.E. Brown Room (Man’s local dialect poet) depicting characters from his Fo’c’s’le Yarns, and produced paintings of Cregneish, one of the oldest villages on the island and the last stronghold of the Manx language. Cregneish residents, their village close by Neolithic stone circles, were believed to be descended from a pre-Celtic race and to possess different racial characteristics from the rest of the islanders (Maxwell Fraser, 1948, 182). To that extent ‘islandness’, a site of unique authenticity, is archived within the island itself.

Hoggatt also contributed to more diverse forms of island tourism. Like many artists during the interwar depression and declining art market, he accepted a number of commissions, including the design of brightly coloured travel posters for the LMS Railway, as did the marine painter Norman Wilkinson for the rail company’s ‘Happy Holidays in the Isle of Man’ series. In this way both connected the Isle of Man most emphatically to the UK mainland and to broader publics. Unique amongst the islands discussed here, Man was more easily accessible to the UK at large, and more fully brought into the ‘mainstream’ with a successful, well-established tourist economy around coastal resorts such as Douglas, and the popular TT (Tourist Trophy) races. In the interwar years 500,000 annual visitors saw First World War foreign nationals’ internment camps turned into holiday camps, with ‘Scotch Week’, the period of the Glasgow holidays, the peak season. A shift in ‘islandness’ here from place of exile, to one of pleasurable escape, however temporary, and a range of commercial attractions and activities that made any coherent sense of island identity difficult to maintain.

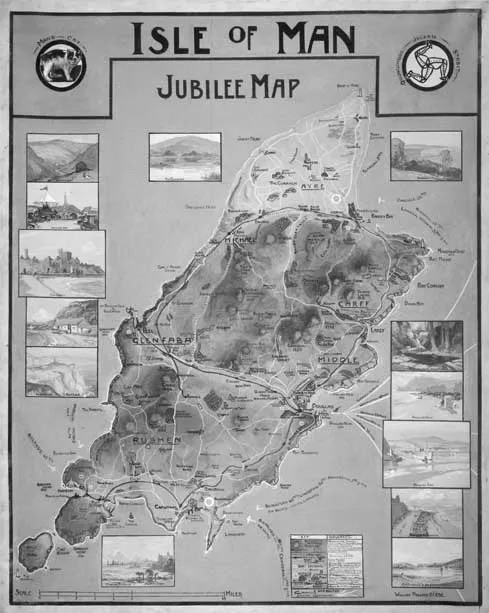

Developments through the 1930s such as Ronaldsway Airport and increased mobility through car ownership, opened up the island for a growing variety of tourist types, hence Hoggatt’s 1935 ‘Isle of Man Jubilee map’ with watercolour vignettes of island attractions. Island ‘mapping’ here contributes to cultural as well as spatial demarcation. Matters of social and cultural distinction obviously dominated the burgeoning national industry of travel guides across the interwar period. In this regard Maxwell Fraser’s In Praise of Manxland, published in the same year as Hoggatt’s map, refers to the artist then living in Port Erin; a notable attraction himself, his works ‘hung all over the Empire’ (Maxwell Fraser, 1948, 181). He who maps the island is mapped in turn.

Figure 1.1 Isle of Man Jubilee Map, William Hoggatt (1935) (permission Manx Museum).

With reference to island racial characteristics Maxwell Fraser’s readers learnt that the ‘Celtic soul’ of the Isle of Man was enriched by the Nordic element, producing ‘happy people, independent in outlook, ready for adventure and fearless on the sea as were the Vikings, but full at the same time of the romance and poetry and music of the Celt’ (1948, v). Appealing to visitors averse to popular coastal tourism and attuned to islands as remote and ancient outposts, Fraser assures distinctiveness: there are ‘no council houses to mar the island’s charm’ (1948, 11).

As these typical examples illustrate, diverse forms of visual culture and related narratives combine across the interwar to produce multiple juxtaposed, often conflicting ‘island’ identities – both forward-facing and backward-glancing – in response to endlessly diversifying, socially and culturally distinctive audiences and markets. The Isle of Man’s identity of course was to change drastically once again in September 1939.

Islands to the West of Scotland

As Hugh MacDiarmid observed, there was ‘hardly an inhabited island of Scotland about which at least one book has not been written’ and most were ‘day-trippers’ ecstasies, trite moralizings, mawkish sentimentality, supernatural fancies’ (1939, Xvii, Vii). The Hebrides are the most continually recorded and described islands throughout this period. Remoteness and isolation more overt than on the Isle of Man; nevertheless greater mobility was reducing distance for some. The motor car enabled one of the most prolific of the interwar writers, H.V. Morton, to follow up his 1927 In Search of England two years later with In Search of Scotland. Doubtless on MacDiarmid’s hit-list, Morton’s narrative on the Hebrides sets a precedent for numerous guidebook clichés about Gaelic peasants, their superstitions and folklore, and its influence perhaps spread more widely i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Islandness and Visual Culture between the Wars

- 2 ‘Stones hard’ and a ‘sea like glass’: Orwell’s Island Pastoral

- 3 Island Geographies, the Second World War Film and the Northern Isles of Scotland

- 4 ‘A hesitation of the tide’: Lindisfarne, Iona, Venice

- 5 ‘All is lithogenesis’: Contemporary Memorials on the Isle of Lewis

- 6 Mac, Son of William McTaggart: Time Travelling Children in Gaelic Island Films

- 7 Fantasy Islands of the Cinematic and Televisual North: Genre and the Location of Anxiety

- 8 Shetland on YouTube: Youth Film in the Northern Isles

- 9 Drawn Together: Patterning Holy Island

- 10 Views over the Sound: Imagining (Northern) Isles as Grounds for Alternative Narratives of Becoming non-Modern

- Index