![]()

Chapter 1

HEMATOPOIESIS AND THE HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL

Anna Rita FRANCO MIGLIACCIO1

1 HEMATOPOIESIS

1.1. INTRODUCTION

Blood is the connective tissue responsible for the homeostatic control of the body. This function is assured by a series of mature cells, each one with a specific function. Since most terminally mature cells are not capable to proliferate and have limited life-spans, they must be replenished on a daily basis by a complex differentiation process defined hematopoiesis. To give an idea of the enormous cellular output of this process, we calculated the number of red blood cells, which are responsible for oxygen transport and delivery, and neutrophils, which are responsible for first-line antibacterial defence, that must be produced every day based on their life cycle. The blood of an average adult has a volume of approximately five litres containing approximately five million red blood cells per microliter. Therefore, the body of an average adult contains a total number of 5×106 × 5×106 = 25×1012 red blood cells which have a life span of 120 days. To assure that red blood cell numbers remain constant, fifty percent of 25×1012 cells (i.e. 12.5×1012 cells) must be replaced every 120 days by newly produced elements. That means that the body generates approximately 1011 new red blood cells every day. As far as the neutrophils are concerned, these cells are present at a concentration of approximately 5,000 cells per microliter of blood, i.e. an approximately total number of 5×103 × 5×106 = 25×109. Since neutrophils have a life span of only 6 hours, to maintain their number constant, our body must produce 12.5×109 new cells every 6 hours, i.e. approximately 6.2×1010 cells every day. Such high numbers of mature cells are produced by a tightly regulated process defined hematopoiesis which in adult life takes place mostly in the bone marrow starting from a highly specialized cell defined the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC).

The HSC was first defined according to the functional definition to be capable to generate itself and all of the mature elements of the blood. This definition arose after lengthy discussion among scholars on whether hematopoiesis was solely a humoral or cellular driven process. Retrospectively, we recognize that both sides of the discussion had value and generated important contributions to the field. The humoral hypothesis was invalidated by the discovery that most of the terminally mature cells are not capable of proliferating but lead to the important discovery of hematopoietic growth factors, such as erythropoietin (EPO), the hormone which controls the production of red blood cells, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF or CSF-3), the growth factor which controls that of neutrophils. These two growth factors are presently mass-produced by recombinant DNA technology and are used in clinical practice to stimulate the generation of differentiated cells under conditions of stress. The cellular hypothesis lead to the discovery of HSC and of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) and to the development of therapies aimed to replace the endogenous populations when they became abnormal and must be eradicated by chemical and/or irradiation means, i.e. allogenic bone marrow transplantation.

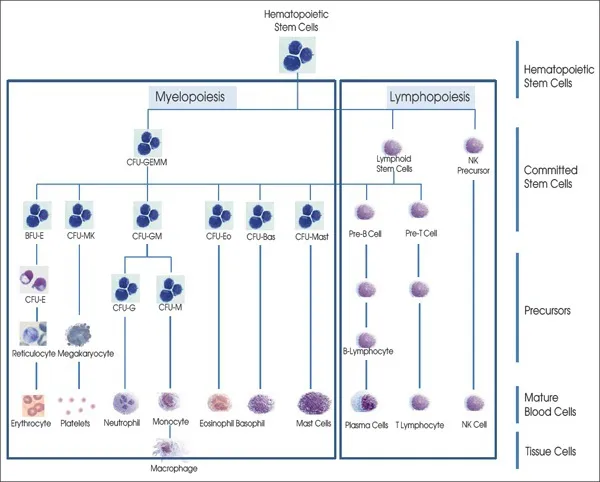

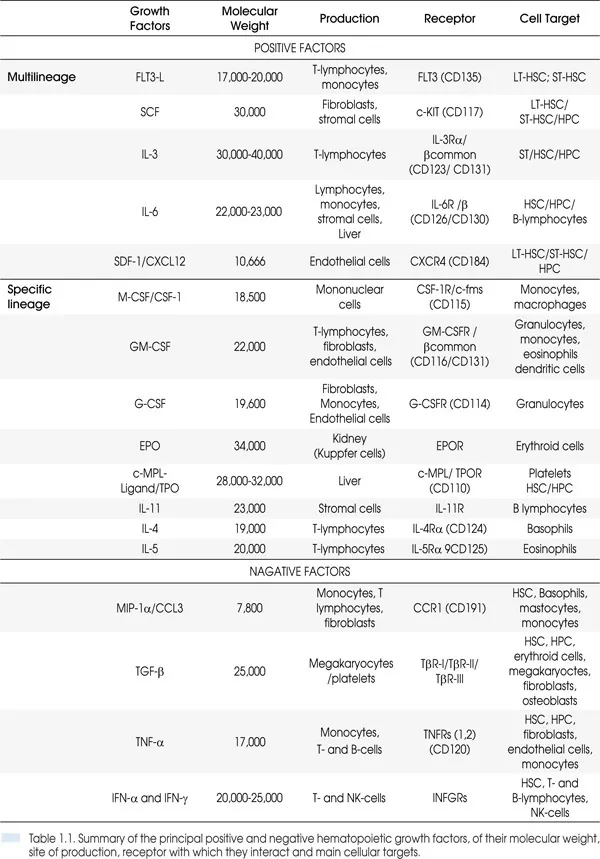

Hematopoiesis, from the Greek words αίμα “blood” and ποιὲω “make”, is a process that starting from HSC generates all the mature cells present in the circulation (red blood cells, platelets, granulocytes, monocytes and lymphocytes). For scholarly purposes, this process is divided into myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis and is tightly regulated not only by soluble factors, some of which were mentioned earlier but also by stromal factors produced by the microenvironment (Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1). Myelopoiesis is divided into erythropoiesis (generation of red blood cells), megakaryocytopoiesis (production of platelets), granulo-monocytopoiesis (generation of granulocytes and monocytes) and occurs mainly in the bone marrow. Lymphopoiesis gives rise to B-cells and T-cells and occurs in bone marrow/spleen/lymph nodes and thymus, respectively. All these processes start from a single HSC which generates a series of cellular compartments (the HPCs) progressively more restricted in their maturation potential through a process defined commitment (Figure 1.2). The commitment process gives rise to differentiated precursors (erythroblasts, megakaryocytes, myeloblast, monocytes and lymphoblasts) which then undergo terminal maturation giving rise to the respective mature cells (red blood cells, platelets, granulocytes, monocytes and macrophages, B- and T-cells) which possess the morphological features necessary to exert their physiological functions. Thanks to the development of loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in mice, much progress has been made in recent years in our understanding of the molecular details of the process of commitment. By contrast, knowledge on the details of terminal maturation is still under development. This chapter will review our knowledge on the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating the early phases of hematopoiesis with a specific focus on myelopoiesis starting from the HSC and ending with the maturation of the differentiated elements.

Figura 1.1. Diagram of the hierarchy of cellular compartments involved in the process of hematopoiesis. HSC and HPC for the different myeloid lineages have similar morphology represented by May-Grünwald staining of a cluster of human CD34

+ cells purified from normal bone marrow. For the nomenclature of the various HPC pupulations see

Table 1.1.

Figura 1.2. Diagram of the hierarchy of cellular compartments involved in the process of hematopoiesis. HSC and HPC for the different myeloid lineages have similar morphology represented by May-Gr

ünwald staining of a cluster of human CD34

+ cells purified from normal bone marrow. For the nomenclature of the various HPC pupulations see

Table 1.1.

1.2. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE BONE MARROW

After birth and throughout adult life, hematopoiesis occurs in the bone marrow, a specialized tissue present within the cavities of the bones. In children hematopoiesis occurs in the cavity of the long bones (femur and tibia) while in adults it occurs mostly in trabecular bones (vertebrae, scapulae, ribs, sternum, pelvis, skull and epiphyses of long bones).

Under physiologic conditions, hematopoietic cells occupy less than 25% of the space within the bone cavity (red marrow) while the remaining 75% of the cavity is occupied by adipose tissue (yellow marrow). The red marrow, however, may expand whenever it is stimulated to produce more mature blood cells. This occurs under conditions of acute and chronic stress (such as massive bleeding, stimulation with exogenous hematopoietic growth factors, inherited forms of anemia such as thalassemia and sickle cell anemia, etc) and allows increasing the production of hematopoietic cells up to 5-8-folds the normal levels.

The bone marrow has a gelatinous consistency and its red regions consist not only of hematopoietic cells but also of a complex system of cells of mesenchymal origin (mesenchymal stem cells and fibroblasts) as well as endothelial cells of the microvasculature and cells of the nervous system which, together with extracellular proteins (fibronectin, collagen, adhesion glycoproteins and proteoglycans) form a scaffold defined as the microenvironment. The microenvironment provides lodging to the cells and regulates the entire hematopoietic process. The red marrow is usually located near the bones in close contacts with the osteoblasts of the endosteum. It has been long recognized that in the marrow hematopoietic cells are distributed in a gradient according to their differentiation potential with HSC preferentially localized close to the bone and progressively more mature HPC distributed toward the endothelium of the microvasculature. Low number of HSC/HPC may eventually egress from the marrow to be released into the circulation. This egression may be increased by natural stress or by chemokine stimulation and involves downregulation of CXCR4, the receptor of CXCR4 ligand (also known as SDF-1) on the cell surface of the HSC/HPC and release of neutrophil proteases (such as MMP-9). This last process is induced by G-CSF. This knowledge has provided the basis for the development of strategies to mobilize HSC/HPC in the blood currently used to collect grafts for autologous or allogeneic transplantation.

The tridimensional architecture of the marrow microenvironment is very complex and sustains hematopoiesis in multiple ways. It provides mechanical support, via a complex system of adhesion molecules, compartmentalization, so that each lineage matures in a discrete location, and regulates the entire process by producing and presenting the extrinsic regulatory signals in a concentration effective fashion. It also provides nurture assuring that specific nutrients, such as iron for the erythroid cells, are available is sufficient quantities.

As hematopoiesis progresses, the various cells must undergo proliferation, epigenetic modifications and morphological remodelling. These processes may or may not occur together.

• Symmetric proliferation. It is the division of a mother cell into two daughter cells with properties similar to its own. This division is associated neither with epigenetic nor morphological changes. Under physiological conditions, it is restricted to HSC which use this mechanism for self-renewal maintaining their number constant throughout life. However, stress facilitates the generation of stress-specific HPC which retain the ability to undergo symmetric proliferation generating more mature cells in less time.

• Asymmetric proliferation. This is the division of a cell into two daughter cells with slightly different functional properties. This division first occurs when HSC begins the commitment process and generates the first multi-lineage HPC and continues with the generation of lineage-restricted HPC and precursor cells. In the erythroid lineage, asymmetric proliferation also occurs in the early phases of terminal maturation while terminal maturation of megakaryocytes is instead associated with endocytosis.

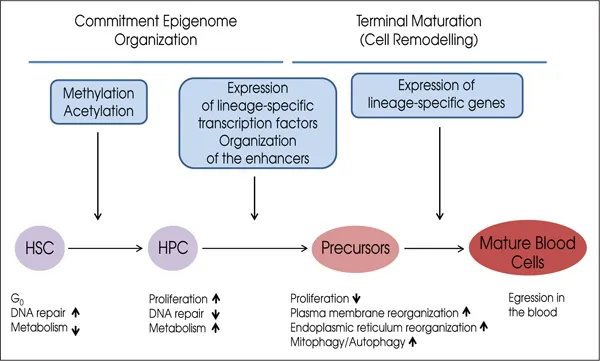

• Differentiation. This is the process during which the HSC generates mature precursors. This process is divided into commitment, during which the genetic information for a specific lineage is imprinted, and terminal maturation, during which the cells undergo morphological remodelling (Figure 1.2).

• Commitment. This process starts at the level of the HSC and generates a series of HPC compartments composed of cells progressively more restricted in their differentiation potential and does not involve changes in cell morphology (Figure 1.1). Commitment involves a series of epigenetic events (DNA methylation and acetylation, activation of the expression of lineage specific transcription factors) which prime the genome of HPC to express genes specific for a particular lineage (Figure 1.2). This priming opens special regions of the chromosomes, defined DNA hypersensitive sites or enhancers, which make the promoters of lineage specific genes accessible to the DNA polymerase to be translated into mRNA. These epigenetic events are usually irreversible although some plasticity may exist. Some cells in the early commitment stages may switch between few alternative lineages in response to stress (for example from the megakaryocytic to the erythroid lineage in response to anemia). This commitment process ends with the generation of precursor cells which are morphologically recognisable because they express some of the features of the final mature blood cells.

• Terminal maturation. This process starts with the first recognizable precursor cell and generates elements with morphology progressively more similar to that of the mature blood cells (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). During this process, the cells transcribe the mRNAs for lineage specific genes and translate them into proteins. The cells also undergo the complex structural changes which allow them to acquire their final functional morphology. The regulation of gene expression at this stage is mostly post-transcriptional and post-translational. Post-transcriptional regulation involves tuning up half-life and ribosome affinity of mRNAs. Post-tra...