- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Book of the Year for The Economist and the Observer

Our world seems to be collapsing. The daily news cycle reports the deterioration: divisive politics across the Western world, racism, poverty, war, inequality, hunger. While politicians, journalists and activists from all sides talk about the damage done, Johan Norberg offers an illuminating and heartening analysis of just how far we have come in tackling the greatest problems facing humanity. In the face of fear-mongering, darkness and division, the facts are unequivocal: the golden age is now.

Our world seems to be collapsing. The daily news cycle reports the deterioration: divisive politics across the Western world, racism, poverty, war, inequality, hunger. While politicians, journalists and activists from all sides talk about the damage done, Johan Norberg offers an illuminating and heartening analysis of just how far we have come in tackling the greatest problems facing humanity. In the face of fear-mongering, darkness and division, the facts are unequivocal: the golden age is now.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Progress by Johan Norberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Food

[W]hoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass, to grow upon a spot of ground, where only one grew before, would deserve better of mankind, and do more essential service to his country, than the whole race of politicians put together.

Jonathan Swift1

One winter’s day in 1868 my great-great-great-great grandfather, Eric Norberg, returned to Nätra in northern Ångermanland, Sweden, with several bags of wheat flour in his cart. He came from a family of ‘south carters’, northern farmers who flouted Sweden’s trade barriers and monopolies by going on long trading journeys. Eric Norberg sold country-woven linens in the south of Sweden and returned with salt and cereals.

Seldom, though, was his return so longed for as on this occasion. It was a famine year. Crops had failed everywhere in the country and those who were short of flour had to mix bark into their bread. A man from the neighbouring parish of Björna recalls his personal experience, aged seven, of those hungry years:

We often saw mother weeping to herself, and it was hard on a mother, not having any food to put on the table for her hungry children. Emaciated, starving children were often seen going from farm to farm, begging for a few crumbs of bread. One day three children came to us, crying and begging for something to still the pangs of hunger. Sadly, her eyes brimming with tears, our mother was forced to tell them that we had nothing but a few crumbs of bread which we ourselves needed. When we children saw the anguish in the unknown children’s supplicatory eyes, we burst into tears and begged mother to share with them what crumbs we had. Hesitantly she acceded to our request, and the unknown children wolfed down the food before going on to the next farm, which was a good way off from our home. The following day all three were found dead between our farm and the next.2

Young and old, haggard and pale, went from farm to farm, begging for something to delay their death from starvation. The most emaciated livestock were tied upright because they could not stand on their own feet. Their milk was often mingled with blood. Several thousand Swedes died of starvation within that year and the next.

Failed harvests were not uncommon in Sweden. A single famine, between 1695 and 1697, claimed the lives of one in fifteen, and there are references to cannibalism in oral accounts. Without machinery, cold storage, irrigation or artificial fertilizers, crop failures were always a threat, and in the absence of modern communications and transportation, failed harvests often spelled famine.

Getting enough energy for the body and the brain to function well is the most basic human need, but historically, it has not been satisfied for most people. Famine was a universal, regular phenomenon, recurring so insistently in Europe that it ‘became incorporated into man’s biological regime and built into his daily life’, according to the French historian Fernand Braudel. France, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, suffered twenty-six national famines in the eleventh century, two in the twelfth, four in the fourteenth, seven in the fifteenth, thirteen in the sixteenth, eleven in the seventeenth and sixteen in the eighteenth. In each century, there were also hundreds of local famines.4

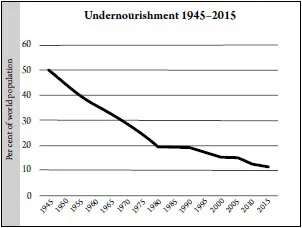

Sources: FAO 1947, 2003, 2015.3

In times of famine, peasants from the countryside turned to the towns, where they crowded together and begged for food and often died in squares and streets, as in Venice and Amiens in the sixteenth century. The cold weather in the seventeenth century made the situation much worse. In 1694, a chronicler in Meulan, Normandy, noted that the hungry harvested the wheat before it was ripe, and ‘large numbers of people lived on grass like animals’.5 They might have been relatively lucky – in central France in 1662, ‘Some people ate human flesh.’6 In Finland, the years 1695–7 are known as ‘the years of many deaths’ when between a quarter and a third of the entire population died of famine.

Braudel points out that this was in privileged Europe; ‘Things were far worse in Asia, China and India.’ They were dependent on rice harvests crossing vast distances and every crisis became a disaster. Braudel quotes a Dutch merchant who witnessed the Indian famine of 1630–1:

‘Men abandoned towns and villages and wandered helplessly. It was easy to recognize their condition: eyes sunk deep in the head, lips pale and covered with slime, the skin hard, with the bones showing through, the belly nothing but a pouch hanging down empty . . . One would cry and howl for hunger, while another lay stretched on the ground dying in misery.’ The familiar human dramas followed: wives and children abandoned, children sold by parents, who either abandoned them or sold themselves in order to survive, collective suicides . . . Then came the stage when the starving split open the stomachs of the dead or dying and ‘drew at the entrails to fill their own bellies’. ‘Many hundred thousands of men died of hunger, so that the whole country was covered with corpses lying unburied, which caused such a stench that the whole air was filled and infected with it . . . in the village of Susuntra . . . human flesh was sold in open market.’7

Even in normal times margins in the most developed countries were exceedingly narrow, and the food not always very nutritious, nor could it be kept very long. Often it had to be procured just before eating. People dried and salted down their food for storage, but salt was expensive. In an ordinary home in my ancestors’ province of Ångermanland a hundred years ago, there were four meals: potatoes, herring and bread for breakfast; porridge or gruel for lunch; potatoes, herring and bread for dinner; and porridge or gruel for supper. This is what people ate every day, except on Sundays, when they had meat soup (if there was any meat) mixed with barley grains. There being no china, everyone ate from the same dish, using a wooden spoon which was afterwards licked clean and put away in the table drawer.8

The importance of adequate nutrition for people’s health and survival has been documented in a disturbing way by a study of life expectancy at the age of fifty in what are now rich countries, at the turn of the last century. It turns out that it is almost half a year longer for those born in the Northern Hemisphere between October and December than for those born between April and June. In the Southern Hemisphere, it is the other way around. Those born in the Northern Hemisphere, who later migrated to the South, also live longer if they were born between October and December. One of the probable reasons for this is that fresh fruit and vegetables were more readily available in the autumn until quite recently, even in rich countries. It seems that nutrition in the womb and early infancy was better for these children, since birth weights were also higher in the autumn.9

At the end of the eighteenth century, ordinary French families had to spend about half their income on grains alone – often this meant gruel. The French and English in the eighteenth century received fewer calories than the current average in sub-Saharan Africa, the region most tormented by undernourishment.10

If you sometimes hear about short working hours in the ancient past, don’t be too envious. People worked as long as they could. The main limiting factor was that they did not have access to the calories they needed for children to grow properly or for adults to maintain healthy bodily functions. Our ancestors were stunted, skinny and short, which required fewer calories and made it possible to work with less food. The economist and Nobel laureate Angus Deaton, who is one of the world’s leading experts on health and development, talks about a ‘nutritional trap’ in Britain in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century: because of this lack of calories people could not work hard enough to produce enough food to be able to work hard.11

It has been estimated that 200 years ago some twenty per cent of the inhabitants of England and France could not work at all. At most they had enough energy for a few hours of slow walking per day, which condemned most of them to a life of begging.12 The lack of adequate nutrition had a serious effect on the population’s intellectual development as well, since children’s brains need fat to develop properly.

Some thinkers at the time assumed this would always be the case. In the eighteenth century, the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus concluded that human numbers would always outrun the amount of food available. He saw that population doubled at an exponential rate – from two to four to eight to sixteen – whereas agricultural production only increased at a linear rate – from two to three to four to five. Whenever food was abundant it would result in more surviving children, which would result in even more deaths later on. Humanity would always suffer from famine, Malthus concluded in 1779:

The power of population is so superior to the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of humanity [infanticide, abortion, contraception] are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the great precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague, advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and ten thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow, levels the population with the food of the world.13

Malthus accurately described humanity’s predicament as it stood. But he underestimated its ability to innovate, solve problems and change its ways when Enlightenment ideas and expanded freedoms gave people the opportunity to do so. As farmers got individual property rights, they then had an incentive to produce more. As borders were opened to international trade, regions began to specialize in the kinds of production suited to their soil, climate and skills. And agricultural technology improved to make use of these opportunities. Even though population grew rapidly, the supply of food grew more quickly. The per capita consumption in France and English increased from around 1,700–2,200 calories in the mid-eighteenth century to 2,500–2,800 in 1850. Famines began to disappear.14 Sweden was declared free from chronic hunger in the early twentieth century.15

However, as late as 1918, in a book about the food situation, the United States Food Administration published a ‘Hunger Map of Europe’, showing the threats to food security in Europe at the end of the First World War. A few countries, such as Britain, France, Spain and the Nordic countries, were deemed to have ‘sufficient present food supply but future serious [shortages]’. Italy had a ‘serious food shortage’ and countries such as Finland, Poland and Czechoslovakia suffered from ‘famine conditions’. ‘Remember,’ the book said, ‘that every little country on the [map] is not merely an outline, but represents millions of people who are suffering from hunger.’16

One of the most powerful weapons against the scourge of hunger was artificial fertilizer. Nitrogen helps plants to grow and some of it is available in manure, but not much. For more than a century, the world’s farmers used bird droppings accumulated over centuries on the coast of Chile, which contained huge quantities of sodium nitrate. But not enough of it was available. Scientists and entrepreneurs thought that there must be some way of fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere, where it is abundant.

The German chemist Fritz Haber, working at the chemical company BASF, was the first to solve the problem. Based on his theoretical work, and after several years of experiments, in 1909 he succeeded in producing ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen. The problem was that he could only do it on a very small scale. There were no large containers that functioned at the temperatures and pressures needed. A colleague at BASF, Carl Bosch, carried out over 20,000 experiments in over twenty reactors before he came up with the right process to synthesize ammonia on an industrial scale. The Haber-Bosch Process made artificial fertilizer cheap and abundant, and soon it was used all over the world.

‘What has been the most important technical invention of the twentieth century?’ asks Vaclav Smil in Enriching the Earth. He rejects suggestions like computers and aeroplanes, going on to explain that nothing has been as important as the industrial fixing of nitrogen: ‘the single most important change affecting the world’s population – its expansion from 1.6 billion people in 1900 to today’s six billion – would not have been possible without the synthesis of ammonia.’ Without the Haber-Bosch Process about two-fifths of the world population would not exist at all, Smil claims.17

Sadly, Fritz Haber’s brilliant mind was also put to the task of killing. He was a pioneer in chemical warfare and developed chlorine gas for the German troops to use against enemy forces. He directed the first release of fatal gas himself on 22 April 1915, at the Sec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Progress

- Praise

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Food

- 2 Sanitation

- 3 Life expectancy

- 4 Poverty

- 5 Violence

- 6 The environment

- 7 Literacy

- 8 Freedom

- 9 Equality

- 10 The next generation

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- Imprint Page