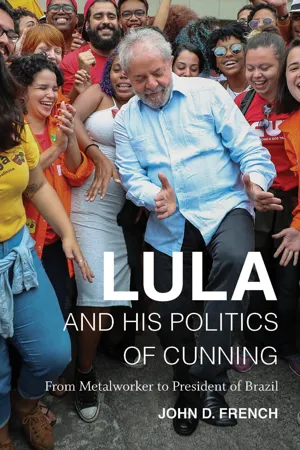

![]()

1 LULA'S APOTHEOSIS

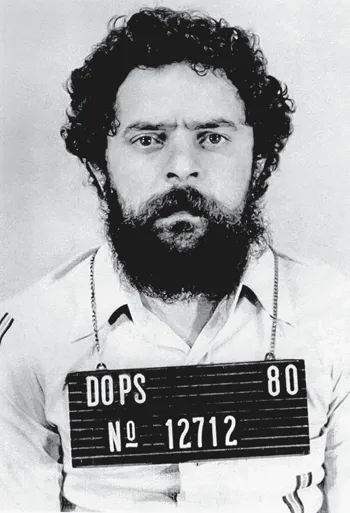

In October 2002 Brazil overwhelmingly elected as president a former metalworker and founder of a socialist party, a man whose family had left the miserable northeastern (nordestino) hinterland five decades earlier, only to face prejudice and hardship in the country's industrial heartland of São Paulo. The election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT) was a clear signal that deep changes were taking place in a country marked by huge social inequalities and a contempt for manual labor engendered by almost four centuries of slavery. The fifty-seven-year-old Lula's election was not only a remarkable personal achievement for a man born into rural poverty but also a sterling tribute to the Brazilian fight to overcome the legacy of the military dictatorship that had ruled from 1964 to 1985. The amazing story of the four decades from the 1964 military coup to Lula's election can be captured in two images. Lula's 1980 police mug shot showed a subversive detained for leading a massive metalworkers’ strike; his presidential portrait of 2003 depicted an older, smiling Lula who would for the next eight years command the very military men who had jailed and persecuted him.

Lula's emergence as a charismatic personality of unquestioned moral authority was linked to events between 1978 and 1980, when workers repeatedly struck the foreign-owned automobile assembly plants in the suburban ABC region of Greater São Paulo. This wave of industrial militancy, which originated among the highest-paid manual workers in Latin America, quickly spread to millions of others over the next three years. As the first mass strikes since the 1964 military coup, the ABC region's work stoppages captured the Brazilian imagination. With 1.6 million residents in 1980, this Latin American Detroit stood out as an extreme example of industrial production on a hitherto-unknown scale. The massive Volkswagen plant in São Bernardo, for example, employed between 35,000 and 40,000 workers in a single complex.

In the late 1970s, Brazil was in the opening phase of a tumultuous struggle for redemocratization, and the strikes of ABC's metalworkers not only “infused extraordinary new energy into the labor movement,” as Margaret Keck has written, but also “fed the image of an increasingly powerful opposition within civil society to continued military rule.”1 The sheer scale and intensity of mobilization in ABC excited awe. In order to accommodate the massive attendance—up to 60,000 workers—the union's general assemblies were held in a local soccer stadium. And in 1980, the workers stayed out on strike for forty-one days despite the army's occupation of the region, the closing of their union, and the arrest of its leaders.

Lula's DOPS mug shot, 1980. (Courtesy President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva)

Lula's presidential photograph, 2003. (Photo by Ricardo Stuckert)

Metalworkers at Vila Euclides with a sign comparing Lula to Jesus. (Photo by DGABC [Reinaldo Martins])

The ABC strikes also catapulted the president of the metalworkers’ union of São Bernardo do Campo and nearby Diadema to national and international prominence. “Luis Inacio da Silva is to Brazil,” the New York Times noted in 1981, “what Lech Walesa is to Poland.”2 As strike participation reached 3 million nationwide by 1980, the charismatic thirty-five-year-old Lula came to personify the combative, grassroots-oriented New Unionism that would take institutional form in 1983 as the CUT (Central Única dos Trabalhadores, or Unified Workers’ Central). In this national trade union confederation's first five years, the newly dynamized labor movement conducted the first truly national general strikes in Brazilian history. As Brazil entered a new democratic era, labor had emerged, in the words of political scientist Alfred Stepan, as the civilian group with “the greatest organizational capacity to continue to militate against those still repressive authoritarian features of the Brazilian State and Brazilian social life.”3

Beyond his innovative contributions to labor mobilization, Lula joined with other trade union leaders in 1979 to call for the new Workers’ Party, which brought labor militants together with radical activists from other social movements, especially liberation theology.4 As New Unionism's political counterpart, the PT was an anomaly, having been built “from the bottom up.” Although it did poorly in the 1982 elections (its candidates received only 3 percent of the national vote), the PT was rooted in society, in its first decade drawing its dynamism from a movement-oriented “logic of difference” that set it apart from the rest of Brazil's political parties.5 Ideologically pluralistic, it emerged as a mass membership party that was surprisingly coherent despite a diversity that ranged from Marxist-Leninists to socially minded liberals.6 Within the Latin American context, the PT was quickly recognized as a sui generis political experiment on the left—a unique “mutational experience,” as Torcuato Di Tella put it. With the global Left in disarray after the fall of the Soviet bloc, Lula and the PT would work to bring Latin America's splintered leftist parties together in the Forum of São Paulo, which acquired broad influence well before the Left's regionwide electoral sweep in the twenty-first century's first decade.7

Shifting from a movement to a party leader, Lula the former trade unionist played a vital role in the popular insurgencies that swept Brazil in the 1980s. In 1984, he attended the founding convention of the Movement of Landless Workers (MST), whose dramatic land occupations made world headlines in the 1990s. And he attended the funeral of PT member Chico Mendes, the leader of the rubber tappers who was murdered in 1988 for fighting to preserve the Amazon for its residents. Serving only a single term as federal deputy (1986–88), Lula the politician preferred to travel the country spreading the gospel of popular organization, protest, and the vote. He contributed decisively, but by no means singlehandedly, to the PT's consolidation as one of the world's largest and most dynamic leftist parties in the 1990s. As they gained municipal office, the PT's elected officials pioneered grassroots “participatory budgeting” mechanisms that gained international recognition. And with the crisis of neoliberalism at the end of the 1990s, the imagination of a surging global justice movement was captured by the World Social Forum (WSF), first held in the PT-ruled city of Porto Alegre in 2001. Against the pro-globalization mantra “There is no alternative” (Margaret Thatcher's TINA), the WSF's “Another world is possible” encapsulated a renewed confidence on the left worldwide.

The PT's dynamic rise can be seen in Lula's increasing success as an electoral politician. In 1989, four years after the return to civilian rule, Lula won 16.1 percent of the vote in the first round of the country's presidential election—its first since 1960—and his vote total rose to 44.2 percent in the runoff; he lost to the favored, center-right candidate by only 5.7 percent. Lula's durable popularity at the polls was confirmed in two subsequent presidential elections. In 1994 he ran first for many months before losing in the first round to the former Marxist sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who received 54.3 percent of the vote to Lula's 27 percent. Four years later, Lula's vote total increased to 31.7 percent in his second loss to Cardoso, who this time received 53.1 percent; it went largely unremarked that support for the president had crested despite widespread acclaim for having produced economic stability by ending hyperinflation. In 2002, by contrast, Lula won 46.4 percent of the vote in the first round and 61.4 percent in the runoff, and in January 2003 he was inaugurated as Brazil's first working-class president. In 2006, Lula was reelected by similar margins, while his personally chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, received 56.1 percent of the runoff vote in 2010 and 51.6 percent in 2014. That Latin America's greatest union leader was the region's most formidable vote getter was amply demonstrated in 2018 when the presidential candidate chosen by Lula—who had been denied his right to run, jailed, and barred from giving interviews—received 44.9 percent of the vote in the second round, against the far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro.

Lula's 2002 election posed new but by no means unwelcome challenges for me as a scholar who has worked on ABC and its workers since 1980, the sixteenth year of military rule in Brazil. Lula's triumph was not an outcome I would have anticipated during my first visit to the country in the summer of 1980, when ABC's metalworkers had just gone down in defeat; their unions were intervened, and Lula and twelve others faced military trials (Lula was sentenced to three and a half years’ imprisonment in 1981, but the sentence was later overturned). Brazil had clearly changed profoundly since then, and Lula's election was a fantastic capstone for the country's hard-won democracy. To find a meaningful equivalent in recent US history, one would have to imagine Martin Luther King Jr. being elected president in 1978, twenty-two years after the Montgomery bus boycott. Yet even this analogy understates the drama, because Lula has only a fourth-grade education—not a PhD, like King—and his impoverished background forced him into the streets at the age of eleven to work as a peddler and shoeshine and delivery boy and, from there, to a factory where, as a teenager, he lost a finger in a press.

An even closer US parallel would be if the trade unionist Eugene V. Debs, a quarter century after leading the dramatic Pullman railroad strike of 1894, had ended up in the White House in 1920 rather than in prison, eight years after he had won 6 percent of the national vote as the Socialist Party's presidential candidate.8 Although both radicalized workers embraced socialism after imprisonment, the drama of Lula's life story dwarfs that of Debs, who was, after all, central to the heartland small-town culture of his nation.9 Lula's family, by contrast, originated in the rural mestiço (mixed race) hinterlands of slaveholding northeastern Brazil. Along with his mother and six of his seven siblings, he made a two-week trek southward on the back of a truck to the hope that beckoned in São Paulo, much like the millions of black and white southerners who poured north to Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland around World War I. And finally, unlike Debs, Silva had a Communist brother, also a trade union leader, whose arrest and brutal torture in 1975 would be the first of many decisive turning points in the life of a twenty-nine-year-old soon to be known by everyone simply as Lula.

The ability of a worker like Lula to move from the streets to the suites via the ballot box is striking from the perspective of the global North. In his sweeping world history of the twentieth century, English historian Eric Hobsbawm noted that structural change in newly industrializing countries like Poland and Brazil could “lead politics in directions familiar in the history of the First World.” The strike that launched the Solidarity movement in 1978–81, he noted, was led by a “bona fide proletarian,” the shipyard electrician Lech Walesa, who vaulted into the presidency of post-Communist Poland in 1990. And the strikes led by Lula, the skilled metalworker, produced a socialist-oriented “political labour-cum-people's party” analogous to the mass social democratic parties of pre-1914 Europe.10 In 2005, Lula was joined in the ranks of Latin American presidents by Evo Morales of Bolivia, another former union leader of working-class origin. Such stories, it may be suggested, are more likely in radically unequal and riven societies like Latin America than in “richer and more homogenous and ‘democratic’ ones in the north with their specialized knowledge elites and developed technologies of governance.”11

Unlike his Polish counterpart, Lula not only won reelection but also presided over a vast country with the world's fifth-largest population. During the boom years of his second term, Brazil's economy grew from the world's tenth in size to the eighth, passing the United Kingdom in 2009. A tireless world traveler, Lula worked to foster a more multipolar world based on respect for national sovereignty and social justice. An ally of Venezuela's controversial president Hugo Chávez, he championed Latin American integration and served as linchpin for the region's growing bloc of Left-led governments. While actively participating in BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) diplomacy, his government sought to unify the developing world to contest the inequities of the international trade and investment regime anchored in the World Trade Organization. Lula was especially committed to the cause of Africa and worked closely with the South African government of the African National Congress and the leaders of the continent's Portuguese-speaking countries.

Domestically, Lula's signature government programs included targeted support for the poorest of the poor on a vast scale as well as a substantial increase in the real value of the minimum wage. He also democratized access to higher education, with decisive support for affirmative action in a majority nonwhite nation. As his second term ended, his stature was buoyed by both his domestic popularity and his country's economic stability in a moment of global crisis. In 2008, the US magazine Time dubbed him one of the hundred people who most affected the world, while the French Le Monde chose him as its person of the year in 2009. That same year, the US business magazine Forbes ranked him thirty-third among the world's most powerful people, and the English Financial Times declared him one of the “fifty faces that shaped the decade.” Such wide international recognition would eventually lead to Brazil being awarded the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. That Lula is a man worthy of study is clear to all, although how to execute such a study still remained uncertain.

Biography's Lies and the Emblematic Temptation

Biography has always been based on a simple lie: the individual's past is recounted in light of his future. Although biography is presented as a seamless birth-to-death narrative, the storytelling actually begins where the life ends, whether in fame or infamy. “The end is taken as the truth of the beginning,” as Jean-Paul Sartre observed in a memoir of his childhood; “a young lawyer is carrying his head under his arm because he is the late Robespierre.”12 Such backward storytelling brings us Lula-as-he-becomes-who-we-already-think-we-know: a vastly popular, widely loved, and much-respected two-term president with a “demotic and larger-than-life personality.”13 In such an emblematic, even iconic, mode of narration, Lula's public life across four decades is overwhelmed by the retrospective meanings ascribed to his rise. The socioeconomic, institutional, a...