![]()

PART 1

THE ACADEMIC AS REFLECTIVE PROFESSIONAL

![]()

chapter 1

THE REFLECTIVE PROFESSIONAL IN ACADEMIC PRACTICE

In this chapter we describe the first of two conceptual frameworks that support the idea of the reflective professional in academic practice. We argue that the three core worlds of ‘student’, ‘teacher’ and ‘researcher’, and the academic encounters between them, are deeply and theoretically inter-related. We contrast traditional assumptions – reflecting models of teaching and research practice pulling these worlds apart – with more recent models, drawing on dialogic views of language and constructivist theories of knowledge that integrate them under a common point of convergence in learning. Finally, we suggest that academic values and principles rest in common models of practice.

INTRODUCTION

In the Introduction we raised the issue of developing a professional language of practice for negotiating the changing context of teaching in higher education. Such a language and its mastery, we suggested, are at the heart of the idea of the reflective professional. Over this chapter and the next we shall examine the conceptual frameworks supporting this professional language of practice. They are:

- a theory of the reflective professional within academic practice; and

- a critical matrix of learning in higher education.

With these two frameworks we set out a theoretical narrative, sustaining the idea of the reflective professional and the associated language of practice. It is not our intention to construct an uncompromising structure in granite but, rather, to disclose the broader theoretical frameworks which practitioners might profitably engage with in their own unique situations.

These frameworks provide a way for understanding the vital role that the academic context plays in the practices of research, teaching and learning at the heart of higher education. In turn, how they are practised reflects underlying theories of knowledge and communication which are shaped by the nature and scope of academic roles and audiences. Being a reflective professional means having the capacity to negotiate and reconcile these different academic worlds – critically and creatively to remake conceptual frameworks which are inherently contestable, uncertain and ambiguous. This also means recognizing the importance of developing a critical capacity to help students negotiate the contestable and ambiguous frameworks they will encounter in their own professional and academic worlds.

In this chapter we describe the first framework informing the language and practice of the reflective professional. We examine contrasting models of teaching and research reflected in the tacit theories employed in their practice and understanding. We compare traditional assumptions, describing models that pull the worlds of practice apart, with models that draw them together under a common point of convergence in learning. Finally, we suggest that academic values and principles rest in common models of practice. We begin, however, by briefly describing two critically important features of this framework: the social-constructivist nature of knowledge and the dialogic quality of language which characterize academic relationships.

THE REFLECTIVE PROFESSIONAL: KNOWLEDGE AND LANGUAGE

Knowledge and social constructivism

The theoretical framework developed in this chapter is constructivist in nature. Constructivism, broadly speaking, refers to the view that knowledge is constructed by individuals through the use of language and other symbolic and cultural systems (Bruner, 1996). While constructivism takes many forms – indeed, Phillips (1995/2000, 2007) has suggested that it has become ‘something akin to a secular religion’ with many rival sects holding different theoretical positions – theorists generally agree on its most basic tenets (Kivinen and Ristelä, 2003). These tenets essentially consist of the view that, despite being born with cognitive potential, humans do not arrive with either pre-installed empirical knowledge or methodological rules. Neither do we acquire knowledge ready formed or pre-packaged by directly perceiving it. On the whole, knowledge – and our criteria and methods for knowing it and the disciplines to which this knowledge contributes – is constructed. There is, however, significant variation between the many theoretical positions described as constructivism and/or social constructivism.

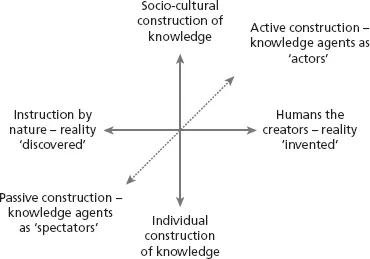

Figure 1.1 Constructivism: three dimensions

Source: Adapted from Phillips, 2000

Phillips describes the variation along three dimensions (see Figure 1.1), which provides a useful map for locating the framework discussed in this chapter. The main horizontal dimension describes the classic disputed ‘reality: discovered or invented’ (see, for example, Penrose, 1989; Rorty, 1989). At one end, knowledge is independent of human agency: nature serves as a kind of ‘instructor’, its store of knowledge discovered and absorbed or copied somewhat passively. At the other end of this dimension, knowledge (and reality) is essentially made or invented by creative and active knowers. At some point towards the ‘discovered’ end of this dimension, a theoretical position is no longer constructivist but takes a strong realist position in which knowledge is in effect imposed from without. There is no effective space for human agency in the formation of knowledge. At the other extreme of this dimension, the theoretical sites take stances describing radical relativist positions. Knowledge is relative to the knower or knowers. It is essentially the result of individual or group invention.

Our position rests between these two extremes, conceiving knowing neither as discovery nor invention but as social narrative. Social narrative, or social constructivism, is addressed by the vertical dimension of Figure 1.1. The vertical dimension of the map describes the tension between theories which contend that the construction of knowledge arises within internal cognitive processes and those which argue that knowledge is socially and culturally constructed and, therefore, largely public. This tension is distinct from the different approaches which theorists take when looking at knowledge and learning.

An approach focusing on the individual and the self does not mean taking a position that regards knowledge as exclusively or even primarily inner or cognitive. Piaget and Vygotsky, for example, are both concerned with how individuals learn and construct knowledge, and approach the subject from an individual psychological perspective, but they differ significantly in their views of what that comprises. Piaget (1950) stresses the biological and cognitive mechanisms, whereas Vygotsky (1986) emphasizes the social factors in learning.

The third dimension focuses on the degree to which the human construction of knowledge, whether it is social and public or inner and private, is an active or passive process. Although there are close parallels here with the first dimension, the tensions inherent in this dimension do not map narrowly on to the first. ‘Spectator’ here is not simply the passive receiver of knowledge from nature and ‘actor’ is not merely the active constructor of personal knowledge. These terms describe a relationship with knowledge which highlights the active involvement, or lack of it, which human agents have in the process of learning. Again, these agents may be individuals or social communities. Our theoretical framework is broadly located on this map close to the middle of the first dimension but leaning robustly along the other two dimensions towards the ‘social’ and ‘active’ poles respectively. Knowing is a social process by which individual experience and meaning are constructed within a system of shared socio-cultural meanings or narratives. As such this book takes a social-constructivist approach to the description of knowledge and human learning.

Language and dialogue

If social constructivism describes the nature of knowledge, dialogue describes the nature of language in which knowledge is shared and developed. Indeed, dialogue is a necessary condition of language and the construction of meaning. The key ideas here may be briefly illustrated by contrasting the views of key theorists of language. The noted linguist Saussure (1966: 9) distinguished language as system (langue) from its use (parole) and notes that in the latter ‘we cannot discover its unity’. The latter, as Holquist (1990: 45–6) notes, is ‘quickly consigned (by Saussure) to an unanalyzable chaos of idiosyncrasy’, and abandoned as an area of study. Bakhtin (1986: 70), however, claimed that such abstractions ignore the active process of the speaker and the role of the other in the actual use of language in favour of vague formal terms (‘signs’) ‘interpreted as segments of language’.

Bakhtin argues that linguistic confusion and imprecision ‘result from ignoring the real unit of speech communication: the utterance. For speech can exist in reality only in the form of concrete utterances of individual speaking people’ (1986: 71). He distinguishes between utterance as a concrete unit of speech communication (inclusive of speaker and situation) and sentence as an abstracted unit in a language system. Bakhtin describes utterance as ‘determined by a change of speaking subjects’. Any utterance, he writes, ‘is preceded by the utterances of others and its end is followed by the responsive utterances of others’ (1986: 71). Speaking (and writing) is by its very nature a response, existing in a stream of related responses and counter-responses distinguished and bounded by a change of speaker, not by full stops and paragraphs. Utterance is defined by dialogue: otherness is presupposed by the speaker as the other to whom the utterance is responding and the other from whom the utterance elicits a response. Language is an intersubjective phenomenon (Rommetveit and Blakar, 1979). It is not possible as a private, individual, subjective activity – see Wittgenstein’s famous (1968) argument against the concept of a private language – nor is it an independent symbolic system. At its core language is essentially dialogue. Dialogue characterizes all forms of human communication and, as we shall see, is therefore critical to the active construction and exchange of knowledge, or the learning, which exemplifies the academic world. The failure to achieve learning in the academic world, moreover, is often grounded in the failure to realize meaningful dialogue and fully permit the active construction of knowledge.

WORLDS APART

The academic world – immersed in its disciplinary and institutional histories, social narratives, discourses and procedures, its ways of thinking and working, of congregating and communicating, of distributing power, authority and status (Becher and Trowler, 2001) – characterizes the student–teacher encounter before a word is even exchanged. It substantially shapes the teacher’s professional experiences and tacitly confronts the student’s first tentative encounters with higher education. For the student, the academic world is typically new and strange, its languages and practices frequently unfamiliar and mysterious, even exotic and bizarre. The student’s encounter with higher education is not simply an intellectual grappling with new ideas, concepts and frameworks, but also a personal and emotional engagement with the situation. If the academic context is more familiar for the teacher, its features more explicit and transparent, the teaching encounter with students is immersed in a host of uneven relationships and concerns, including the status of teaching in higher education.

Often unknown to students, teaching has become the poor relation to research and scholarship. The relative status of teaching to research is exacerbated by the financial rewards and status that accompany the latter even as, ironically, concerns on both sides of the Atlantic can be heard to improve the status of the former (US Department of Education, 2006; HEA, 2007). At the heart of the struggle is an all too pervasive understanding that teaching is something an academic does, whereas research and scholarship are what make an academic special. Where many students approach learning in higher education, hesitant and uncertain, cautiously embracing new cultures and ways of thinking, an increasing number of teachers (including many with a natural love of teaching) approach the teacher–student encounter with ambivalence and an underlying sense of dissatisfaction.

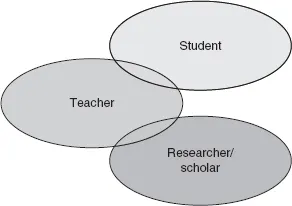

There is, then, in the general teaching and learning situation an imperfect encounter of three worlds of experience – student, teacher and researcher – which, ironically, are defined by one another in substantial ways and yet separated by underlying tensions. The teacher, for example, is a teacher in so far as he or she has students. Students, however, do not fully share a world with their teacher, and there is, by definition, a disparity in the knowledge and expertise each possesses. The teacher, moreover, has the authority to teach the particular subject of a discipline in higher education by virtue of his or her work as a researcher or scholar, and yet teaching is typically viewed as detached from and even undermining research. Teaching detracts from the time and effort available to put into research and often contributes to a reduction in the status of the academic, as if being good at teaching precludes one’s ability to be a good researcher (Boyer, 1990; Colbeck; 1998, Wolverton, 1998). Teaching so conceptualized has built into it the seeds of its own undoing: it undermines the research and scholarship that provide the authority to teach in higher education. Teaching contests and diminishes itself by definition. Evidence of this may be seen, for example, at the doctoral level, where the less research and scholarship an academic does undermines their authority to both attract and supervise postgraduates. The correspondence and tensions between the three worlds describing teaching in higher education (see Figure 1.2) characterize the ways in which dialogue and learning occur or do not occur within the myriad situations of these three worlds.

Figure 1.2 The worlds of teaching

The quality of the meaning and learning achieved in these situations and associated practices is dependent on the extent and quality of the correspondence. How much of the potential correspondence do we permit in practice? How much do we exclude? In a narrowly construed correspondence, we construct situations that reduce the potential for the construction of meaning, irrespective of the quantity of meanings used. In such situations, dialogue can descend into a mechanical and linear process. The listener is effectively detached from the speaker, not because there is nothing to say but, rather, because the social situation militates against it. Dialogue becomes monologue. Meanings are merely transmitted across the situation rather than mutually constructed within it. Deeper meaning is not achieved. The potential for dialogue and the realization of genuine engagement within such fragmented situations and encounters is minimal.

The challenge for professionals in higher education (and it is not limited to those engaged directly in teaching and learning) is to find ways of critically engaging (reflecting and acting) and integrating the academic worlds in which they practise. In the next section we will consider these issues by explorin...