Geocomputation

A Practical Primer

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Geocomputation is the use of software and computing power to solve complex spatial problems. It is gaining increasing importance in the era of the 'big data' revolution, of 'smart cities', of crowdsourced data, and of associated applications for viewing and managing data geographically - like Google Maps. This student focused book:

- Provides a selection of practical examples of geocomputational techniques and 'hot topics' written by world leading practitioners.

- Integrates supporting materials in each chapter, such as code and data, enabling readers to work through the examples themselves.

Chapters provide highly applied and practical discussions of:

- Visualisation and exploratory spatial data analysis

- Space time modelling

- Spatial algorithms

- Spatial regression and statistics

- Enabling interactions through the use of neogeography

All chapters are uniform in design and each includes an introduction, case studies, conclusions - drawing together the generalities of the introduction and specific findings from the case study application – and guidance for further reading.

This accessible text has been specifically designed for those readers who are new to Geocomputation as an area of research, showing how complex real-world problems can be solved through the integration of technology, data, and geocomputational methods. This is the applied primer for Geocomputation in the social sciences.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I Describing how the World Looks

1 Spatial Data Visualisation with R

Introduction

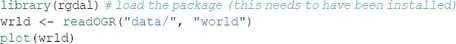

What is R?

With the advent of ‘modern’ GIS software, most people want to point and click their way through life. That's good, but there is a tremendous amount of flexibility and power waiting for you with the command line. Many times you can do something on the command line in a fraction of the time you can do it with a GUI.

Why R for Spatial Data Visualisation?

A Practical Primer on Spatial Data in R

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Describing how the World Looks

- 1 Spatial Data Visualisation with R

- 2 Geographical Agents in Three Dimensions

- 3 Scale, Power Laws, and Rank Size in Spatial Analysis

- Part II Exploring Movements in Space

- 4 Agent-Based Modeling and Geographical Information Systems

- 5 Microsimulation Modelling for Social Scientists

- 6 Spatio-Temporal Knowledge Discovery

- 7 Circular Statistics

- Part III Making Geographical Decisions

- 8 Geodemographic Analysis

- 9 Social Area Analysis and Self-Organizing Maps

- 10 Kernel Density Estimation and Percent Volume Contours

- 11 Location-Allocation Models

- Part IV Explaining how the World Works

- 12 Geographically Weighted Generalised Linear Modelling

- 13 Spatial Interaction Models

- 14 Python Spatial Analysis Library (Pysal): An Update and Illustration

- 15 Reproducible Research: Concepts, Techniques and Issues

- Part V Enabling Interactions

- 16 Using Crowd-Sourced Information to Analyse Changes in the Onset of the North American Spring

- 17 Open Source GIS Software

- 18 Public Participation in Geocomputation to Support Spatial Decision-Making

- Conclusion: The Future of Applied Geocomputation

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app