chapter one

introduction

Pragmatism, a termite ‘undermining foundations, collapsing distinctions, and deflating abstractions’.

(Menand 1997: pxxxi)

BORN OUT OF a passionate desire to improve design quality and a recognition that this can only happen through education, the main premise of this book is that a radical redefinition of the relationship between the senses and intelligence is long overdue. Written primarily from my perspective as an experienced teacher and practitioner of landscape architecture, the problems are not specific to this discipline alone, but are equally relevant to architecture, urban design and other art and design disciplines, as well as philosophy, aesthetics and education more generally. Deliberately crisscrossing the carefully demarcated boundaries and borders between philosophy, theory and practice, it aims to demonstrate the very real practical consequences of philosophical ideas and the philosophical lessons that can be learned from practice. The argument it puts forward helps clarify and resolve the great design riddle: why it is still largely considered to be unteachable and how we can dismantle this antiquated supposition, constructing in its place a means of dealing with spatial, visual information that is artistically and conceptually rigorous.

One of the main preoccupations of contemporary cultural discourse has been the argument for and against the existence of universal truth. By carrying this argument into the perceptual realm and adopting a pragmatic line of inquiry which questions the very nature of foundational belief, it becomes possible to offer an alternative, interpretative view of perception. With this one pivotal adjustment, the whole metaphysical edifice built on

the flawed conception of a sensory mode of thinking comes tumbling down. Constructed in its place is a means of dealing with spatial, visual information that is artistically and conceptually rigorous. This book examines some of the implications of this paradigm shift for design theory and education.

Although rarely articulated, the concept of the sensory interface is hugely pervasive, affecting almost every facet of Western culture. It lies at the heart of a common assumption that art involves a different conceptual framework from science, a different mode of thinking. It also underpins the idea that art is a pleasurable pastime whereas science is a serious endeavour, that it is possible, indeed preferable, to forget all you know in order to fully appreciate a piece of music, a painting or the landscape, embracing the sensuality of the experience with a clean slate, uncontaminated by knowledge or rationality. Why, despite so much evidence to the contrary, we still characterise scientists as cool, detached, unencumbered by emotion and artists as passionate, subjective and slightly deranged. Why we think decisions can be made on the one hand intuitively, without knowledge and on the other objectively, without value judgements. That language is linear and the emotions irrational and that

theory is separate from practice. At the centre of aesthetic experience, the sensory mode of thinking is what those learning to design are expected to reap the benefits of, if they are to be in any way successful. It distances nature from culture and makes it practically impossible to develop a holistic view or vision of the landscape.

Growing concern about the destruction of the environment in the name of development and the potentially dire consequences of climate change have at last pricked our collective consciousness. Cities across the world have strategies for sustainability, creativity and cultural identity. There is at last, a tangible recognition that the physical, cultural and social condition of our environment has a profound effect on the quality of life and is a vital component of sustainable economic growth. We know that good-looking quality places lift the spirit and have a dramatic effect on people’s morale, confidence and self-worth. Dreary, unkempt, dysfunctional places make people feel unvalued and resentful. It’s common sense really, a statement of the obvious. It’s just a pity it’s taken some of us so long to realise it. Now, it has become a political reality and we all have a responsibility.

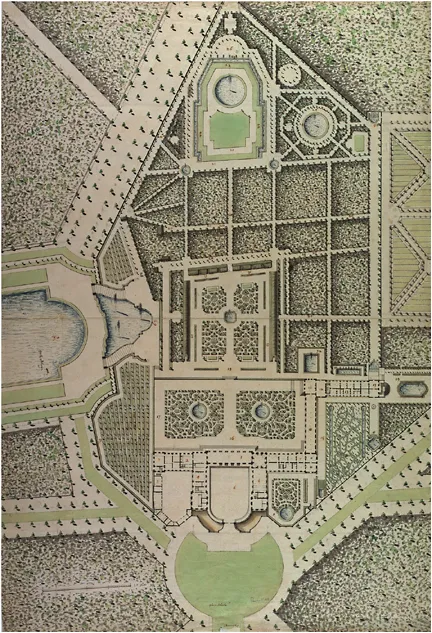

So what do we mean by the art of design? I first saw this remarkable design at an exhibition of landscape drawings from 1600–2000 currently on display at Het Loo in Appledoorn. I remarked to my colleagues that it would be wonderful if a student handed in a drawing like that. Wondering who had designed it we peered at the text and found it was by le Notre; it was his design for the gardens of the Grand Trianon at Versailles, accompanied by eight pages of manuscript connecting image and concept, ideas and form.

It is remarkable for many reasons. It exhibits astonishing skill and confidence in the expression of ideas in form, through technology, with elegance and panache. Far from being a slave to the geometry of the plan, the asymmetrical design is an imaginative manipulation of the spatial structure of the landscape, intensifying perspectives, foreshortening views, skewing natural crossfalls and creating vistas, connecting seamlessly with the landscape beyond. It is responsive to the topography and context, culture and time. Extraordinarily knowledgeable, skilfully exploiting the full range of the medium, this design is there to manipulate the emotions, express power and control movement. This is what the art of design is about. There is no mistaking its brilliance – if you know what to look for.

A powerful cultural force is currently undermining any serious attempt to develop the kind of expertise le Notre exhibits. It is, of course, possible to teach many aspects of design. There are books on design theory, criticism, history, its technology and modes of communication. There are guides on collaboration, team building and how to carry out design reviews. But large chunks of the actual design process, the real nitty-gritty of the discipline, are clouded by subjectivity and therefore thought to be beyond teaching. Design is often characterised as a highly personal, mysterious act, almost like alchemy, adding weight to the dangerous idea that it is possible, even preferable, to hide behind the supposed objective neutrality implied by more ‘scientific’, technology-based, problem-solving approaches. Talking about excellence is actually considered somehow undemocratic and elitist. It is this kind of dogmatism that impacts so negatively on our thinking about design.

The crux of the problem is that an intractable rationalist paradigm dominates our thinking to such a degree we no longer give it much thought. All manner of assumptions, suppositions and tall tales have moved beyond question and become self-evident, obvious and largely taken for granted. It is this philosophical tradition that actually prevents us from having informed discussions about the significance of the way things look, the material, physical qualities of what we see. Reinforced by a host of beliefs and suppositions it exiles materiality to a metaphysical wilderness where it languishes, separated from intelligence, safely hidden out of sight, out of mind.

This paradigm is manifested in the interface thought to exist between us ‘in here’, and the real world ‘out there’, apparently helping to correlate, crystallise, process or structure our sensory impressions to serve intelligence. It’s called many things – a sensory modality, visual thinking, the aural or tactile modality, the experiential, the haptic – the latest I have come across is unfocused peripheral vision. Whatever it’s called, however it’s characterised, it is there to pick up the really important stuff. It sifts the wheat from the chaff, sorts out the things worth noticing. Discriminating on our behalf, it helps us understand the world. Dig deep enough however and all you find are value judgements masquerading as universal truth, the ‘real’ truth that exists ‘out’ there if only we look hard enough, or are lucky enough to be clever enough, or sensitive enough to find it.

No one knows how all this really works. The actual mechanics of it remain a mystery, or as Jay puts it ‘somewhat clouded’ (Jay 1994: 7). From a pragmatic point of view, this perceptual whodunit is insoluble because the entire plot is based on a rationalist belief in different modes of thinking and pre-linguistic starting points of thought, a set of assumptions that have been with us so long they have become part of common sense. Ironically, despite all the post-modern rhetoric, concepts such as visual thinking, intuition, language, emotions, artistic sensibility and design expertise remain imbued with the fundamental Cartesian distinction between body and mind, between facts and values, real truth and mere opinions. It is a metaphysical duality that slips under the intellectual radar, disguised in visual and perceptual theories.

The consequences for those studying to become designers and ultimately for the places they create are potentially devastating. Nullifying any educational rationale for substantial areas of decision-making, within the arts there is instead a misguided dependence on concepts such as creativity, the genius loci, ideation or the mind’s eye, delving into the subconscious or sharpening intuitive responses. This causes a good deal of confusion and bewilderment often reducing design education to an arbitrary second-guessing of what the tutor likes or otherwise leaving students either hoping they can somehow pick ‘it’ up as they go along, or left wondering what on earth ‘it’ is all about.

Whilst this makes what designers do seem rather mysterious and intriguing, it is, in fact, deeply questionable. The scant regard for materiality it engenders in design theory can only serve to obfuscate the understanding of any spatial, visual medium. But the implications of an imagined sensory interface are far more wide reaching. Responsible for the continuing distinction made between theory and practice, the separation of ideas from form, emotions and intelligence and a host of other misconceptions, it thwarts design pedagogy, fuelling the myth that anything other than the purely practical or neutrally functional is a bit iffy, too subjective, a matter of taste really and best avoided. Giving the impression that concepts such as artistic rationality, aesthetic sensibility and design expertise are

contradictions in terms rather than credible educational objectives, it baulks any attempt to provide a convincing rationale for art education, still generally regarded as ‘nice but not necessary’ as Eisner reluctantly admits (Eisner 2002: xi). The prevalence of this dogma explains why a premium is out on reading or writing rather than drawing. We are not learning to be aware of our surroundings, to recognise our responses to place and space, and are rarely shown why things look like they do given the time, place or context. All things aesthetic remain firmly off limits. It is just not polite to use the ‘A’ word. More generally, it skews the way intelligence is defined or what counts as valid knowledge and gives a prejudicial and narrow view of the role of language. The same implacability militates against arguments for resources, space, time or money in competition with more so-called ‘rational’ disciplines. The upshot is that many theorists and those who are not practising designers can find it very difficult to imagine the effort, knowledge and skill it takes to work out the spatial qualities of a design. An eminent academic specialising in the role of drawing and design for example, asked why architects spend all that time drawing – why don’t they just draw what they see in their heads and forget about all that sketching business? University administrators, struggling to understand why studios, expensive in terms of real estate, are necessary, ask why design can’t be taught like mathematics or business studies with lecture rooms crammed full of students, as well as asking why all that expensive tutorial time is wasted hunched over a drawing board. It plays havoc with the academic and research standing of art and design disciplines and makes it difficult to mount hard-nosed political arguments about the social and economic value of g...