- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'In life, I want students to be alive and on stage I want them to be artists' Jacques Lecoq

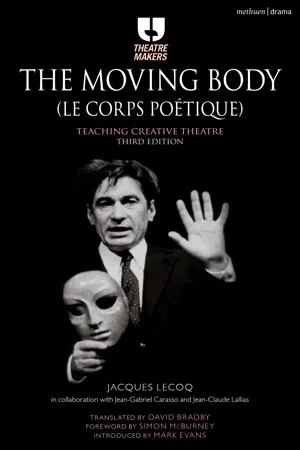

Jacques Lecoq was one of the most inspirational theatre teachers of our age. In The Moving Body, he shares with us first-hand his unique philosophy of performance, improvisation, masks, movement and gesture, which together form one of the greatest influences on contemporary theatre.

Neutral mask, character mask and counter masks, bouffons, acrobatics, commedia, clowns and complicity: all the famous Lecoq techniques are covered in this book - techniques that have made their way into the work of former collaborators and students including Dario Fo, Ariane Mnouchkine, Yasmina Reza and Theatre de Complicite.

The book contains a foreword by Simon McBurney, a critical introduction by Mark Evans and an afterword by Fay Lecoq, Director of the International Theatre School in Paris.

Jacques Lecoq was one of the most inspirational theatre teachers of our age. In The Moving Body, he shares with us first-hand his unique philosophy of performance, improvisation, masks, movement and gesture, which together form one of the greatest influences on contemporary theatre.

Neutral mask, character mask and counter masks, bouffons, acrobatics, commedia, clowns and complicity: all the famous Lecoq techniques are covered in this book - techniques that have made their way into the work of former collaborators and students including Dario Fo, Ariane Mnouchkine, Yasmina Reza and Theatre de Complicite.

The book contains a foreword by Simon McBurney, a critical introduction by Mark Evans and an afterword by Fay Lecoq, Director of the International Theatre School in Paris.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

III

The Roads to Creativity

Clown performance by second-year students

Geodramatics

At the end of the first year, about a third of the students are chosen to go on into the second year. The selection process may be a difficult, sometimes a painful one, and we are not infallible. But we try to be as fair as possible, weighing up the actor without wounding the person, and our choices make no claim to predict what students may go on to do. The main criterion for selection is the actor’s capacity for play. This does not mean that, in their future lives, all will choose to become actors. Some will follow other paths, into writing or directing. But the dramatic terrain explored in the second year can only truly be experienced through performance when developed to its highest level, so students have to prove they have great qualities in this area. A true understanding and knowledge of theatre inevitably requires a profound experience of play.

In the course of the first year we shall have planted the roots, enriched the soil, turned over the earth. We shall have completed three journeys: first, the observation and rediscovery of life as it is through replay, thanks to the freedom conferred by the neutral mask; second, we shall have raised the levels of playing, by means of expressive masks; finally, we shall have explored the poetic depths of words, colours, sounds. The first year will have built up a very precise body of work which will remain as our point of reference. Come what may, a tree is still ‘The Tree’, and we shall need to continue our practice of observing it.

The second year, however, is very different. It does not form a logical continuation of the first, but a qualitative leap towards another dimension: geodramatic exploration of huge territories with one single objective: dramatic creation.

We start with physical and gestural languages. Next we embark on the grand emotions of melodrama, followed by the human comedy of commedia dell’arte. The second term is devoted to bouffons, then tragedy and its chorus and finally to mystery and its madness. Clowns and comic varieties (burlesque, eccentric, absurd, etc.) occupy the third term. The year begins in tears, moves through the experience of collaborative chorus-work and ends in solitude and laughter.

This sequence we work through in the second year explores the different facets of human nature. Melodrama involves us in grand emotions and the pursuit of justice. In commedia dell’arte we discover the human comedy: little wheelings and dealings, petty deceptions, hunger, desire, the rage for life. Bouffons caricature the real world, underline the grotesque aspects of all hierarchies of power. Tragedy evokes a grand popular chorus and the destiny of the hero. Mystery questions everything that remains incomprehensible, from birth to death, the before and the after, the devil who provokes both the gods and our imaginations. Lastly, the clown has the freedom to make people laugh, by showing himself as he is, entirely alone.

But there is always a danger that students will rely on the cultural references which come with these dramatic territories. Each of us has his own way of imagining the past, the pictures he has seen, the books he has read, his own particular clichés too. Everyone claims to know what melodrama was, what commedia dell’arte and tragedy were, but who can say how tragedies were really performed in Ancient Greece, or commedia dell’arte in Renaissance Italy? No reading of reference books can substitute for creative work, renewed each day in the school. Beyond styles or genres, we seek to discover the motors of play which are at work in each territory, so that it may inspire creative work. And this creative work must always be of our time.

My method aims to promote the emergence of a theatre where the actor is playful. It is a theatre of movement, but above all a theatre of the imagination. In the course of the second year, we shall not just aim to see and to recognise reality, but to imagine it, to give it body and form. Our method is to approach the ‘territories of drama’ as if theatre were still to be invented.

We emphasise the poetic vision in order to develop the creative imagination of our students. But we must never lose our grasp on the essential thing, that is to say the motors of play which arise from the natural dynamics of human relations and which audiences recognise immediately. The dynamics I refer to are the shared references which are indispensable for both actors and spectators. They are at work in all forms of theatre, including the most abstract. Reality can also be found in abstraction! We need to continually check these dynamic laws of theatre. That is why the second year is largely oriented towards writing, in the sense of the structuring of play. An actor can only truly play when the driving structure of the written play allows him to do so.

We do not deal with the symbolic dimensions of drama, as exemplified in Asian theatre traditions. Such traditions demonstrate symbolic theatre that has crystallised into its perfect form. When matter becomes saturated, it crystallises into a geometric form which is fixed and immutable. This quality characterises the Japanese Noh and the Kathakali. They have reached perfection in forms which are ideal for what they aim to achieve. Although the actors in these traditions must, of course, inhabit these forms, and nourish them, they do not have to invent them. I prefer to work on theatres whose forms are still open to change and renewal.

Three sets of questions guide our geodramatic exploration:

(1) What are the stakes that are being played for? What part of human nature is brought into play in melodrama, commedia dell’arte, tragedy? What elements of human behaviour and which bodies do they set in motion? What are the dramatic motors driving these forms of theatre?

(2) Which are the most appropriate stage idioms or languages for expressing these stakes? Half-masks, real objects, chorus? How do these languages work and how may they be combined?

(3) Which plays to choose? Which dramatic texts can best enrich the exploration of each of the territories?

The second year is based on these three questions, supported by a simple demand that all the students ‘tell us a story’.

1

Gestural Languages

From pantomime to cartoon mime

Before beginning to explore dramatic territory, we begin the second year by working on gestural languages, taking physical expression in the different directions set out below. The purpose of this approach is to enrich all the students’ subsequent investigations by providing them with a shared vocabulary in the languages of gesture.

In pantomime, gestures replace words. Where speech uses a word, a gesture must be found to signify it in pantomime. The origins of this language are partly in fairground theatre, where performers had to make themselves understood in a very noisy environment, but mostly in the ban on speaking that was served on the Italian actors, to prevent them from competing with the Comédie Française.1 Pantomime was born from a constraint similar to that found in prisons, where convicts communicate by gesture, or in the Stock Exchange today. Its technique, which is partly traditional – one need only think of Deburau2 – is a dead end for the theatre, and the only escape is through virtuosity. It requires an ability to draw objects and images in space, to come up with symbolic attitudes (some of which are found in oriental theatre).

Pantomime which restricts itself to a gestural translation of words is what I call white pantomime – a term borrowed from the period when Pierrot was a central character. Its technique relies mainly on hand gestures, supported by the attitude of the body. Inevitably, it requires a special syntax which is different from that of spoken language. ‘You are pretty, come with me, let’s go swimming’ becomes: ‘You and me … you pretty … go together … swim … over there.’ A different logic is needed for the construction of phrases, which demands clarity, economy and precision of meaning.

Students often try to repeat gestures from everyday life which are borrowed from the language of pantomime. In fact, pantomime requires highly developed gestures which go beyond the everyday and establish a different rhythm from that of spoken language. Another pitfall is to replace every single word with a grimace. We have to recover a use of the face as ‘mobile mask’, one which can change expression in the course of a sentence, according to the feelings expressed, but not word by word.

Figurative mime, the second language we study, consists of using the body to represent not words but objects, architecture, furnishings. Two main possibilities are open to the actor: either to use his body to play a door, which another actor will open and close (the body of one thus becoming the stage set for the other), or the actor creates in space the virtual reality of a house – the roof, the walls, the windows, the door – so that it takes shape for the spectators, and so that the character can then go in and out. Although it has its limits, this language facilitates a technical approach to the articulation of gesture and will prove fruitful later on.

Cartoon mime, a language which is close to silent cinema, uses gesture to release the dynamic force contained within images. Rather than the actor representing words or objects on his own, this language is made up of images expressed collectively. Let us imagine a character going down into a cellar by the light of a candle. The actors can represent both the flame and the smoke, the shadows on the walls and the steps of the staircase. All these images can be suggested by the actors’ movements, in silent play. One of the first exercises consists of building sequences of images; for example, the sequence we created one day, based on a visit to Mont-Saint-Michel.

The students began by suggesting the Mont-Saint-Michel seen from the distance, using their hands, then their bodies, alone or in small groups. Then, gradually, they took us into the picture. The place grew before our eyes, we moved onto the causeway, leaving the sea on both sides. We entered the gateway of the fortified city, going along the narrow street. We reached the restaurant of La Mère Poulard, then, through their images, we entered the restaurant, landed up in a plate, inside an omelette, and finished, along with the omelette, absorbed into the body of the diner.

This kind of continuous travelling shot requires the use of a widely varied gestural repertoire. It is worth noting that computer-generated images of virtual reality operate according to the same mechanism.

In their auto-cours I ask a group of students to recreate a whole film without words, using only gestures. Cartoon mime can make use of any cinematic technique: close-ups, long-shots, illusions, flashbacks, in short the whole repertoire of the modern language of moving pictures, with its rhythms, its brilliance, its ellipses, all transposed into the dimensions of theatre.

A deeper stratum of this research led us to explore the hidden gestures, emotions, underlying states of a character, which we express through mimages. These are a kind of ‘close-up’ on the character’s internal dramatic state. Feelings are never performed or explained, but the actor produces lightning gestures which express, through a different logic, the character’s state at a given moment (a sort of physical aside commenting on one phase of the performance).

A person has to go and see his boss to ask him for something. He arrives in front of the door, and is filled with a sense of anxiety: ‘What shall I say to him?’ At this precise moment, gestures provide an image of his feeling. Not explanatory gestures describing his state, but much more abstract movements which allow him to exteriorise elements which are naturally hidden in everyday behaviour. He knocks on the door, enters, he is afraid. Here again, the actor does not play fear by trembling or stammering; the fear within him is given gestural form, either by him alone or by another actor, or several. These lightning gestures demonstrate to the spectators an ‘echo’ of the character’s fear which, of course, the other protagonists cannot see.

Storyteller mimes apply these different languages to the telling of stories. The idea is to tell a story by alternating between (sometimes by combining) the different gestural languages and the tale being told. This can be done solo, where the same actor is both storyteller a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Dedication Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Biographical Note

- Bibliography and Filmography

- Translator’s Note

- I Personal Journey

- II The World and Its Movements

- III The Roads to Creativity

- IV New Beginnings

- Glossary

- Notes

- Afterword

- Copyright Page

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Moving Body (Le Corps Poétique) by Jacques Lecoq, David Bradby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Teatro. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.