![]()

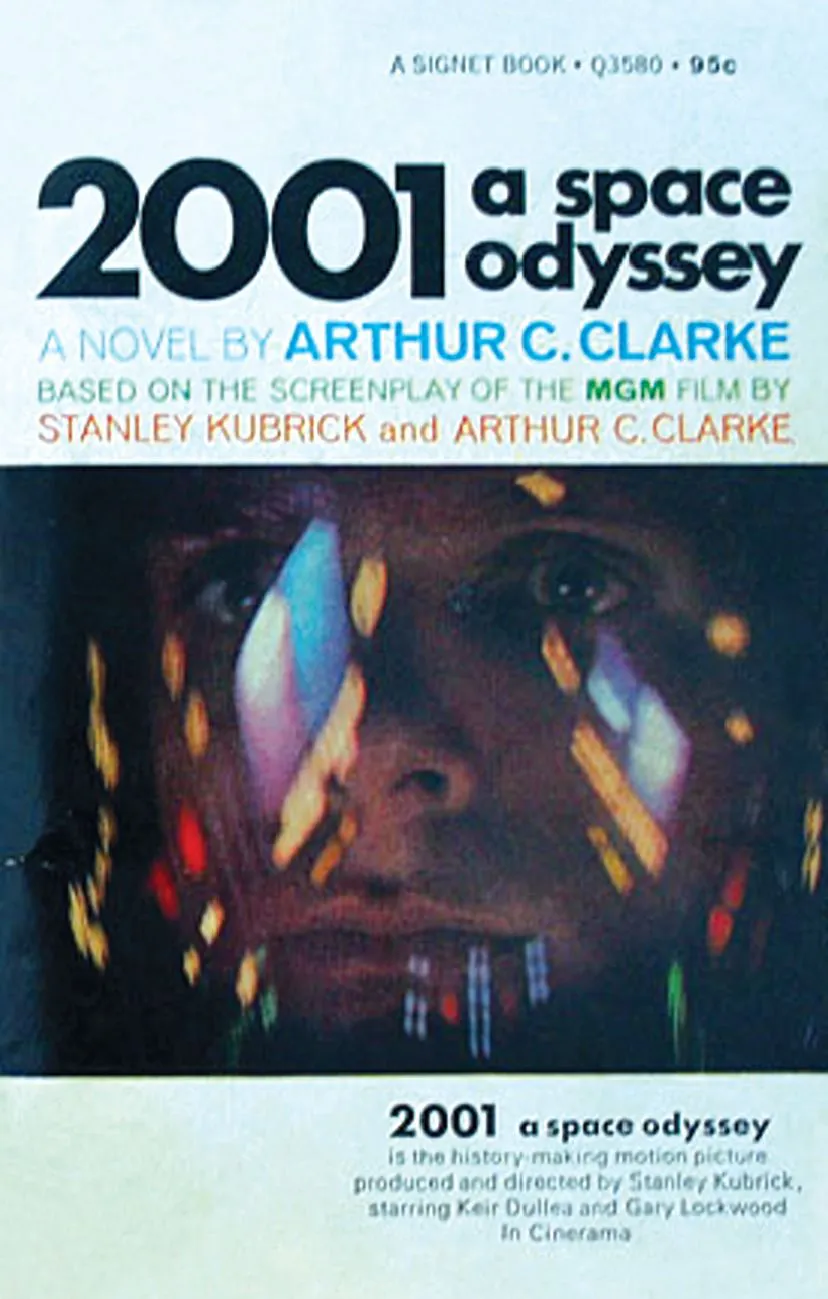

1 The Novel

The beginning is ominous: ‘The drought had lasted now for ten million years, and the reign of the terrible lizards had long since ended.’14 This is the first sentence of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The chapter in which it appears is entitled ‘The Road to Extinction’, referring to the ‘man-apes of the [African] veldt’ who are ‘already far down’ this road and about to join the ‘terrible lizards’ (i.e. dinosaurs) in oblivion when the story begins three million years ago.15 The fate of the ‘man-apes’ – or hominids – is changed when one band, headed by a male called ‘Moon-Watcher’, encounters a ‘completely transparent’, ‘rectangular slab’, a ‘crystal monolith’, which turns out to be a technological device created by explorers from outerspace with the intention of transforming the hominids – through sounds and images and the direct manipulation of their brains – into users of tools.16 Because Moon-Watcher and his band learn how to use stones, sticks and bones as weapons with which to kill animals and members of rival bands, they are able to survive and prosper, laying the foundation for their descendants to evolve into ‘Man’, who, by the second half of the twentieth century, has long ‘conquered his [sic] world’, yet lives ‘on borrowed time’ because weapons have evolved as well, gaining ‘all but infinite power’.17 Thus concludes the first part of the novel, entitled ‘Primeval Night’.

The remainder of the novel tells the story of how, at the turn of the twenty-first century, three further encounters with monoliths left by the ancient extra-terrestrial explorers lead to the transformation of one human descendant of Moon-Watcher’s band into a ‘Star-Child’.18 The second part of the novel opens with scientist and presidential adviser Dr Heywood Floyd’s reflections on the ‘excitement’ of leaving Earth and on the imminent danger of its nuclear devastation: ‘he wondered if it would still be there when the time came to return’.19 Floyd visits the American Moon colony to discuss a three-million-year-old black monolith which has been excavated in the crater Tycho, yet has been kept a secret due to the ‘immense’ ‘political and social implications’ of the discovery.20 While Floyd examines the monolith, it is triggered by its first exposure to sunlight and sends a signal ‘towards the stars’.21

Parts three to five deal with the spaceship Discovery’s journey to Saturn, which turns out to be the target of the alien device’s signal. Because ‘the highly advanced HAL 9000 computer, the brain and nervous system of the ship’, commonly referred to as ‘Hal’, has to keep the true goal of the mission secret from the two astronauts David Bowman and Frank Poole, it suffers a mental ‘breakdown’, killing Poole and three hibernating astronauts, before in turn being disconnected by Bowman.22 On the Saturn moon Japetus, Bowman then discovers a giant monolith, which functions as a ‘Star Gate’, installed three million years earlier by the extra-terrestrials, who in the meantime have ‘become creatures of radiation, free … from the tyranny of matter’, yet who ‘still watched over the experiments their ancestors had started’.23

The novel’s sixth and final part, ‘Through the Star Gate’, describes Bowman’s journey across the galaxy to an ‘elegant, anonymous hotel suite’ constructed by alien intelligence ‘twenty thousand light-years from Earth’, where he is reborn as an ‘immortal’ ‘baby’.24 Following the appearance of another monolith, the Star-Child, comforted by the certainty that ‘[w]hen he needed guidance in his first faltering steps, it would be there’, is transported back to the vicinity of Earth where he (it?) decides to detonate the nuclear weapons orbiting the planet – ‘because he preferred a cleaner sky’.25 The Star-Child is now ‘master of the world’ and ‘history as men knew it would be drawing to a close’.26 Humanity’s future depends on what the new master decides ‘to do next’, but instead of outlining this future, the novel comes to an abrupt end; its last sentence merely announces that the Star-Child will ‘think of something’.27

As readers, we cannot be sure whether the Star-Child’s detonation of nuclear weapons in Earth’s orbit is the beginning of a nuclear holocaust, or, on the contrary, the first step of a campaign to remove the threat of such weapons. The book’s ending refers back to an earlier chapter, which relates how Moon-Watcher first uses a weapon to kill another hominid and concludes almost exactly like the book as a whole: ‘Now he was master of the world, and he was not quite sure what to do next. But he would think of something.’28 The following chapter is entitled ‘Ascent of Man’. This suggests that the book’s conclusion also marks the beginning of a new evolutionary development, now characterised by the ascent of beings that are post-or superhuman. In this context, Moon-Watcher’s murderous violence could be seen to serve as a contrast to the peaceful means and intentions of the much more highly evolved Star-Child, or, on the contrary, to prefigure its even greater murderousness.

The ambiguity of the book’s ending can hardly be resolved this way, nor does the description of the extra-terrestrial beings whose monoliths are responsible for both evolutionary leaps provide a clear-cut answer. Having ‘found nothing more precious than Mind’, they have used ‘godlike powers’ to nurture and protect the emergence of intelligence and consciousness on Earth and elsewhere in the universe: ‘They became farmers in the fields of stars; they sowed, and sometimes they reaped. And sometimes, dispassionately, they had to weed.’29 Indeed, when Bowman arrives in the alien hotel room, he suspects that he is being subjected to ‘some kind of test’, the outcome of which could determine ‘not only his fate but that of the human race’.30 Does his subsequent transformation into the Star-Child mean that he and humanity have passed the test, or is it the Star-Child’s task to decide, on behalf of the extra-terrestrials, whether humanity has to be weeded out? As we saw earlier, despite his original intention to offer an optimistic ending, Clarke later acknowledged the validity of a pessimistic reading as well, thus affirming the fundamental ambiguity of the ending.

In novel form, then, 2001 deals with ultimate questions arising from evolutionary biology, historiography, current affairs, futurology and religion, questions about the ever-present threat of extinction each species has to confront in nature, about the (natural and not-so-natural) forces at work in human evolution, about the origins and future of humankind and its potential for nuclear self-destruction, about the judgment that may one day be passed on humanity and the consequences of such judgment. The film, by contrast, does not include any explicit references to nuclear weapons or to the environmental plight of the hominids, which lessens the expectation of imminent extinction so pervasive in the novel. Nor does the film offer any explanation for the origins and function of the monoliths, and it never even mentions their almost godlike builders, which means that their potentially negative judgment of humanity never becomes an issue – except, as we have seen, for those who approach the film with knowledge of the novel.

Now that we have a good sense of how the project turned out in the end, let’s look at its very beginnings.

![]()

2 Origins

On 31 March 1964, two months after the release of his latest film Dr Strangelove, which consolidated his reputation, at the age of only thirty-five, as one of Hollywood’s most controversial and most successful film-makers, Stanley Kubrick wrote to Arthur C. Clarke about ‘the possibility of doing the proverbial “really good” science-fiction movie’.31 He suggested a meeting ‘to determine whether an idea might exist or arise which would sufficiently interest both of us enough to want to collaborate on a screenplay’. The scripts of all of Kubrick’s previous seven features had been the result of his close collaboration with other people, mostly novelists rather than established scriptwriters,32 and the last five had been based on novels. It is therefore not so surprising that Kubrick approached a novelist about a possible joint project. But why did he want to make a science-fiction movie?

With this last film, Kubrick had already entered the realm of science fiction, insofar as Dr Strangelove extrapolated from the technology and politics of the present to depict possible developments in the near future, building up towards the explosion of a ‘doomsday device’. In addition to this extrapolation, during the writing of the script Kubrick had considered a science-fiction framing device, whereby the film would begin and end with voice-over narration which represented the point of view of an extra-terrestrial civilisation in the distant future, looking back on a decisive moment in the history of the long-dead planet Earth.33 The opening voice-over, accompanied by images of outer space, was to point out that the ‘odd story’ about to be told had unfolded on Earth because ‘the full consequences of nuclear weapons seemed to escape all governments and their people’.34 The film was to end with the camera pulling away from the Earth into space and the narrator commenting that the events of this ‘quaint comedy’ took place at a time ‘when the primitive organisation of sovereign nation states still flourished, and the archaic institution of War had not yet been forbidden by Law’.35 The script thus provided – through the example of a much wiser extra-terrestrial civilisation – an alternative to humanity’s nuclear self-destruction, in which the true horror of nuclear war could be recognised, the division into nations overcome and military conflict abandoned.

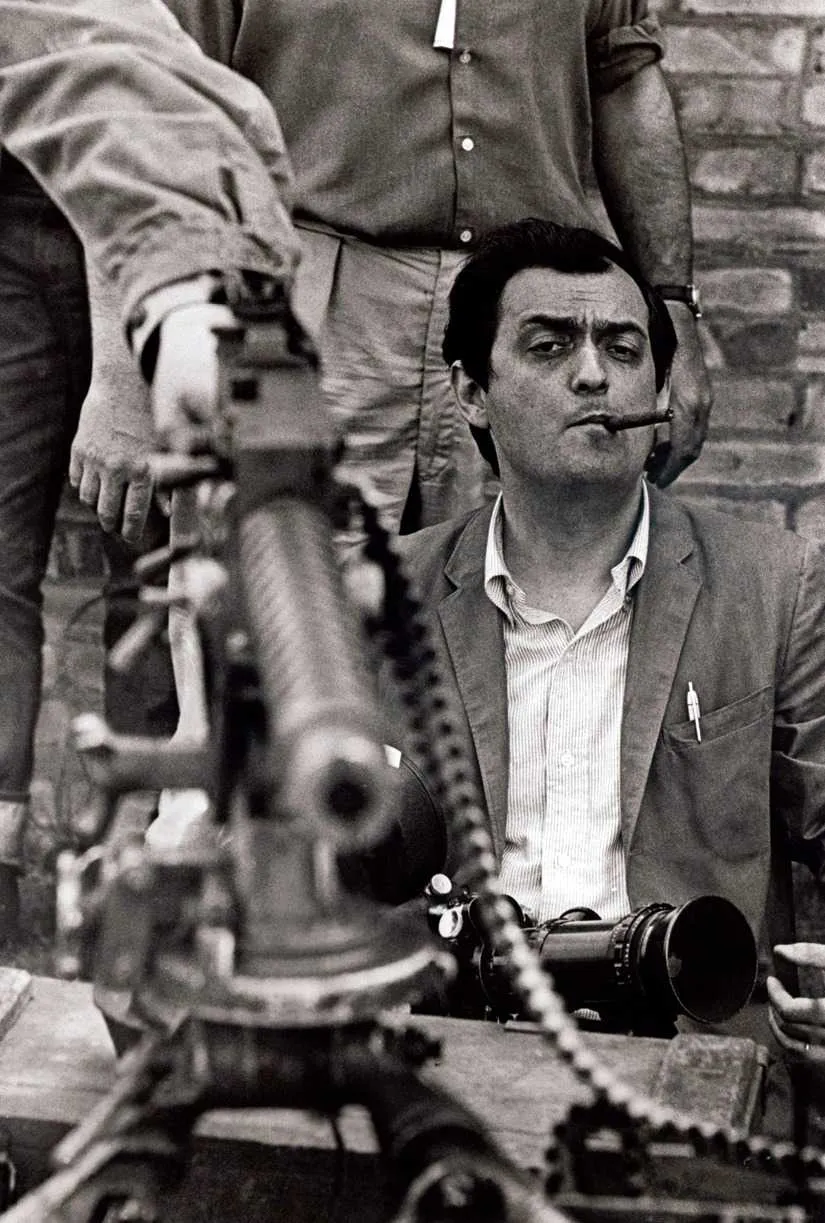

Stanley Kubrick during the making of Dr Strangelove

These references to extra-terrestrials provided a direct link to Kubrick’s next project, because, in his letter to Clarke, he identified as his own ‘main interest’ – ‘naturally assuming great plot and character’ – the following three themes:

1.The reason for believing in the existence of intelligent extra-terrestrial life.

2.The impact (and perhaps even lack of impact in some quarters) such discovery would have on Earth in the near future.

3.A space-probe with a landing and exploration of the Moon and Mars.

The abandoned framing device of Dr Strangelove thus gave rise to the serious investigation of humanity’s relationship to other intelligent life in the universe. This investigation would allow Kubrick to develop the idea from the Dr Strangelove script that extra-terrestrials could offer an alternative to humanity’s self-destruction. If, rather than having its ruins examined by aliens thousands of years from now, humanity made contact with extra-terrestrials ‘in the near future’, might this help to unify it and thus to prevent earthly conflict? Also, might there be lessons to be learned about the pitfalls of using hugely destructive technologies from an advanced civilisation that had long mastered such use without destroying itself?

By the early 1960s, questions like these were being frequently addressed in science fiction, in the widespread discussion of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) and in scientific debates about extra-terrestrial life, all of which Kubrick had probably come across during the initial research for his new project in the months, perhaps even years, before he first wrote to Clarke.36 In science-fiction films and literature, for example in Clarke’s work, humanity’s division...