- 213 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bacterial Starter Cultures for Food

About this book

This book brings together information concerning starter culture bacteria in the manufacture of many milk, meat, vegetable, and bakery products. The characteristics and functions of these bacteria in the production of cultured foods, as well as factors which affect their performance, are discussed in detail. Topics include the role of plasmids in starter culture bacteria, the function of these bacteria as food preservatives, nutritional and health benefits, and future applications. Authors provide historical background as an introduction to each chapter. This will be a valuable reference book for food industry technologists and academicians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bacterial Starter Cultures for Food by Stanley E. Gilliland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Stanley E. Gilliland

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Historical Development of Cultured Foods

- Development of Starter Cultures

I. Historical Development of Cultured Foods

The discovery of the process of converting foods into new forms having different, yet desirable properties or characteristics, was probably accidental. In early biblical times certain foods, such as milk, were probably placed under conditions that resulted in an alteration of the products. The resulting altered food product likely possessed new characteristics including taste, aroma, texture, and appearance. Not only would such changes in the product have produced a new food product to add variety in the diet, but also a product that could be saved for later use. The new form provided a food that would not spoil as easily as the original raw product. Perhaps the most significant effect of such fermentations was the preservation of the food.

No knowledge existed at the time concerning bacteria, much less the specific ones involved in the food fermentations. The desired change was controlled, probably more or less by the manipulation of the raw products with regard to substances added, the container, and the temperature at which the product was held. Additionally, treatment of the product after the fermentation very likely added to the characteristics of the product. The method of preparing the product undoubtedly must have involved a certain amount of trial and error in selecting the method of handling that created the most desirable new product. The overall procedures probably varied from one group of people to another. This would have resulted in a wide variety of fermented foods. The converted foods resulting from the growth and action of microorganisms under rather crude conditions were the predecessors of the wide variety of cultured foods we have today.

II. Development of Starter Cultures

Through the years it was found that the fermentation process was improved by saving part of the fermented product to start the next batch. This represents the first use of starter cultures.

Cultured foods as we know them today, including such products as yogurt, buttermilk, hundreds of varieties of cheeses, many varieties of fermented sausages, and fermented vegetables and breads, probably all can be traced back to foods that were allowed to undergo a normal or natural fermentation under rather crude conditions. If we accept this, these fermentations would have occurred due to microorganisms included in the natural flora of the raw food product. The environment under which the raw product was placed (in addition to substances added to the raw food) would have resulted in conditions that selected for the desirable type of microorganism. Much variation probably occurred in the creation of fermented food products. The production of such cultured food products would be considered an “art” rather than a science.

The bacteria included in starter cultures of today in many cases include those bacteria that predominated in the historical fermented foods. Such cultures have been developed by isolating those same bacteria. Most cultured foods today are manufactured under sanitary and controlled conditions to help ensure that the desired bioconversion occurs in producing the converted food product. In many cases, especially with milk products, the food is exposed to treatment such as heat prior to adding the starter culture in order to reduce the number of undesirable microorganisms. This is done to ensure that the starter culture is able to produce the desired change in the product. In many cases, however, it is not possible to heat the product prior to fermentation so that competing bacteria may be destroyed.

The primary genera of bacteria included as starter cultures include Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, and Propionibacteria. Most of these genera have one thing in common: they produce lactic acid during their growth in the food products (Propionibacteria are the exception). Thus for most cultured food products, lactic acid becomes a very important component. The result is that most cultured foods share one common characteristic — sourness or tartness with regard to taste.

Over the years, the starter culture industry has undergone tremendous development. More knowledge has developed concerning the starter culture bacteria involved in milk fermentations than for any of the other cultured foods. However, a great deal of information is currently being added concerning the microorganisms used in the manufacture of other cultured foods. Today, not only do we use specific strains or mixtures of strains of known species of bacteria as starter cultures, but we possess vast knowledge concerning factors influencing their activity. Activity is defined as the relative ability of the organism to rapidly carry out the desired change in the food product being cultured. The techniques for producing, handling, and using starter cultures has changed over the years. We are entering a new era where the role(s) of plasmids and genetic engineering are being investigated to learn more about the biological factors that control starter culture activity, and to develop new and improved strains that will more efficiently produce cultured food products. Many of these aspects will be discussed in subsequent chapters of this book.

Starter culture bacteria are very important in converting food into new products and exerting preservative actions on the food. Their influence with regard to exerting preservative actions involves antagonistic action toward other types of microorganisms. This aspect of starter culture activity has created interest in applying starter cultures to foods that traditionally do not undergo fermentation in order to enhance their preservation. In addition to their preservative action, considerable information has been collected indicating that starter cultures can provide certain nutritional and health benefits. These aspects are also discussed in subsequent chapters.

Chapter 2

The Streptococci: Milk Products

William E. Sandine

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Historical

- Taxonomy

- Functions

- Isolation and Enumeration

- Metabolism

- Citrate

- Lactose

- Glucose

- Genetics

- Factors Affecting Optimum Performance

- Inhibitors in Milk

- Strain Compatibility

- Temperature

- pH

- Growth Media

- Bacteriophages

- Capsule Production

- Storage

- Variation

- Testing Strains

- Conclusions

References

I. Historical

Streptococci, both the saprophytic and parasitic species, occur in milk because of their fastidious nature. Here, they find a source of carbohydrate (lactose), protein breakdown products, vitamins, lipids, and minerals, all of which they need for growth. The natural reservoir for members of the Streptococcus genus is green plant material and here these bacteria also find the nutrients needed for growth. Because of the close association of milk production with green plants, it is natural that streptococci would enter the milk supply, especially under the milk production conditions existent in earlier times. Hand milking of cattle into open containers easily resulted in the contamination of raw milk with a variety of organisms, including the streptococci. Along with members of the Lactobacillus genus, they played an important role in the natural souring of the milk important in preventing the growth of undesirable pathogens and spoilage bacteria; this ultimately led to our understanding of the use of certain selected lactic acid bacteria in the manufacture of the many fermented dairy products that are available today.

Because of their occurrence in milk, the streptococci were among the first genus of microorganisms to receive research attention by bacteriologists. The review articles by Sherman,1 Hammer and Bailey,2 Sandine et al.,3 and Lundstedt4 present the historical information summarizing many of the early studies done with these bacteria. Since this chapter concerns the streptococci in milk products, most of the information will be confined to the lactic streptococcal species. Members of the other three streptococcal groups (viridans, pyogenic, and enterococcus) also occur in raw milk and the enterococci are prevalent in certain fermented products, especially cheese.

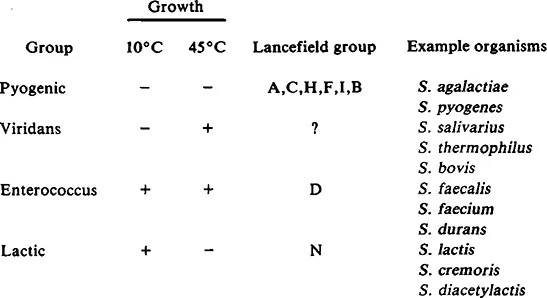

II. Taxonomy

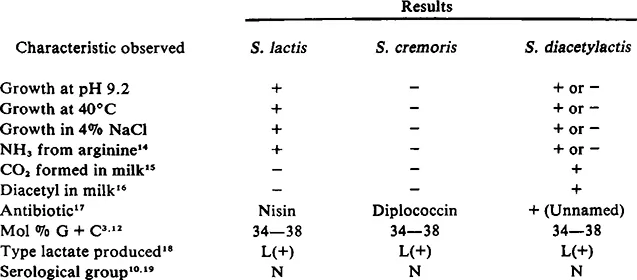

From the studies of a number of investigators, particularly the early work of Storch,5 Conn,6 Weigmann,7 Orla-Jensen,8 Lister,9 Hammer and Bailey,2 Lancefield,10 and Sherman,11 we are able to place isolates of streptococci into one of the four groups mentioned above. Table 1 shows these groupings and lists the principal characteristics of the most important species present therein. All but the lactic group contain potentially pathogenic organisms and it is principally from this group that selected isolates are taken for use as starter cultures in the preparation of fermented dairy products. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the organisms in the lactic streptococcus group. Though they form a rather homogeneous group genetically,12 the lactic streptococcal group contains three easily identifiable species or, as they are now called, subspecies.13 These are Streptococcus lactis subsp. lactis, S. lactis subsp. cremoris, and S. lactis subsp. diacetylactis. These are usually referred to as S. lactis, S. cremoris, and S. diacetylactis, respectively.

Many other names for organisms that are legitimate members of the lactic group have been used by various scientists and appear in the literature. These have been given varietal designations such as “tardus” to refer to slow acid-producing types, “hollandicus” to refer to capsule-producing types, “maltigenes” to refer to malt-flavored strains,20 and “aromaticus” to refer to strains with variable or weak abilities to ferment citric acid. It seems appropriate to refer to certain lactic streptococcal strains as varieties of the appropriate species when one wants to emphasize a particular stable characteristic of a designated strain.

Considerable confusion existed in the early days of research on the “streptococci” that fermented citric acid and produced diacetyl plus carbon dioxide. Two different genera were involved and the rather inert “associative organisms” often found in milk and fermented dairy products were at first proposed as belonging to the Betacoccus

genus,8 but were later placed in the Leuconostocgenus;21 these bacteria are the subject of a separate chapter in this book. The lactic streptococcus called S. diacetylactis is also a flavor-producing organism by virtue of its ability to ferment citric acid with the production of diacetyl, acetoin, 2,3-butylene glycol, and carbon dioxide.

Table 1

GROUPS OF STREPTOCOCCI

GROUPS OF STREPTOCOCCI

Table 2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LACTIC STREPTOCOCCI

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LACTIC STREPTOCOCCI

III. Functions

The lactose-fermenting and resultant acid-producing capability of lactic streptococci enable them to perform several important functions in milk and milk products. In cheese they concentrate and stabilize the curd by coagulating the protein and expelling moisture. They also prevent or discourage growth of undesirable spoilage and pathogenic bacteria by reducing the pH. They thereby contribute to the texture and can contribute either directly or in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Copyright Page

- The Editor

- Contributors

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Streptococci: Milk Products

- Chapter 3: The Leuconostocs: Milk Products

- Chapter 4: The Lactobacilli: Milk Products

- Chapter 5: The Lactobacilli: Meat Products

- Chapter 6: The Propionibacteria: Milk Products

- Chapter 7: The Pediococci: Meat Products

- Chapter 8: The Lactobacilli, Pediococci, and Leuconostocs: Vegetable Products

- Chapter 9: The Lactobacilli and Streptococci: Bakery Products

- Chapter 10: Types of Starter Cultures

- Chapter 11: Concentrated Starter Cultures

- Chapter 12: Roles of Plasmids in Starter Cultures

- Chapter 13: Role of Starter Culture Bacteria in Food Preservation

- Index