![]()

1

'Festering Britain': the 1951 Festival of Britain, decolonisation and the representation of the Commonwealth

Jo Littler

The 1951 Festival of Britain has been re-imagined and resurrected in many different guises. For commentators on the left it has been a symbol of the last, flamboyant, gasp of social democracy before the onset of 1950s conservatism; as the festival of the left, against which the 1953 Coronation neatly becomes the festival of the right.1 To design historians the Festival marks the emergence of self-consciously modern mass-market commodity aesthetics.2 In social histories of Britain, it is often invoked as emblematic of post-war hedonism and of the desire to move from austerity to affluence.3 For museologists the Festival can be positioned as part of a tradition of large, national temporary expositions - as part of a more or less cohesive Western genre stretching back to Crystal Palace, and across to the Expositions Universelles and the World's Fairs. This role, written into the plans from the start (it was in part produced as an anniversary monument to the 1851 Great Exhibition) has been elaborated more recently with the consistent invocation of the Festival as a superior precursor of the Millennium Dome.4

Many other Festivals have or could be produced: versions highlighting its significance in terms of modern architecture and planning; its focus on leisure; or perhaps its relationship to people's emotional lives, personal histories and secrets. What has rarely been discussed, however, and what is now only starting to be paid some attention is the relationship of the Festival, to the effects of decolonisation and the formation of the Commonwealth.5 This lack of attention has in part been because the Festival did not have the graphic connection with empire of, for example, the 1851 Great Exhibition or the 1924 Empire Exhibition, with their carefully staged living history displays of subordinate natives and imperial triumph.6 It is also symptomatic of the broader absence of attention to the effects of decolonisation on British culture, which has only recently become subject to more sustained academic attention in areas such as history, politics, visual culture and cultural studies.7

Consisting of events held up and down the country, the Festival of Britain has now mainly and merely become synonymous with the exhibitions on the specially regenerated area of London's South Bank that was often taken at the time to be its centrepiece. What was defined as 'the Commonwealth participation' in the Festival consisted of only a handful of practices; most conspicuous were the exhibitions held at the Imperial Institute in South Kensington under the banner The Festival and the Commonwealth, which received minimal publicity. It also involved the government graciously letting the Dominions and Colonies know that they had permission to celebrate too, and asking them for donations of raw material, alongside various sporadic forms of Commonwealth participation, such as the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO) playing at the South Bank.

However, the reason for this limited role was not because the Empire was not being thought about. On the contrary, the issue over whether and how great a role the Commonwealth should play, and to what extent the Empire should be represented, was described during an early meeting of the Festival's Council as 'a matter of the highest policy'.8 Some members of the Council argued that 'the whole purpose of the festival would be destroyed if it did not demonstrate to the world Britain's greatest contribution to civilisation - namely the foundation of the British Empire.'9 Empire was a subject of tense consideration and negotiation for the planning committee and the government: it did not simply slide out of view.

Yet, at the same time, arguments for more representation of empire and Commonwealth lost, and the degree to which empire was officially represented was clearly being scaled down, reflecting the moment that John MacKenzie has described as the first in a series of colonial 'implosions' from 1947 onwards. Becky Conekin's recent groundbreaking work on the Festival has shown that many involved in the practicalities of planning the celebrations wanted empire to be absent, whether consciously or not. This was partly due to its controversial nature as a topic (Charles Plouviez, Assistant to the Director of Exhibitions, wrote that 'it would have been immensely unpopular with half our audience') and partly due to the planners' sympathies for a left-wing anti-imperial modernity (as opposed to the more imperial sentiments of the Festival Council, stuffed as it was with a high proportion of 'the great and the good'). This anti-imperialism was motivated, she indicates, mainly by an economic nationalism that had become harnessed to US interests, which saw imperial discourse as anti-modern, and felt slightly queasy about such relations of domination in the aftermath of the Second World War.10

As Stuart Ward has recently emphasised, 'the meanings of imperial decline were neither uniform nor universal', and so equally as many different stories might also be told about the relationship between the Festival and decolonisation as about the Festival itself.11 This chapter seeks to extrapolate several different discourses on British national identity which have visual currency around the Festival and which were being constructed in relation to the decline of empire and to the formation of the Commonwealth. To do this I use a variety of visual media sources, including cartoons, adverts and magazine images as well as archival records of exhibition narratives (all of which are helpful in considering the wider 'life' of an exhibition through their cross-promotional presence in the media). This also helps us consider how the Festival's relationships to decolonisation were manifest in less officially delineated ways, as imperial and post-imperial discourse were constructed in ways that were not necessarily prescribed by the planning committee.12

Drawing together a range of material and drawing out their implications, what is explored here is a hypothesis that 'Festival culture' employed three main registers to negotiate the continuing legacy of colonialism: a predominantly sublimated discourse of neo-imperial mastery, a discourse of commonwealth 'benevolence', and a discourse of insular national parochialism. This is not to say that such discourses were clearly self-contained and demarcated; nor is it to say that they did not overlap. Rather, it is to attempt to use these categorisations as a means of discussing frequently recurring sentiments, assumptions and motifs, and to attempt to understand their significance.

Imperial mastery

As Catherine Hall succinctly puts it, after 1945 'the colonial order fell to pieces and was replaced, in theory at least, by a "world of nations" and, in the British context, a Commonwealth of nations'.13 The entity termed 'the Commonwealth' signified both the moves towards decolonisation14 as the empire crumbled, and the attempt to maintain and reinscribe some of the power dynamics of imperialism (Churchill for instance famously saw it as 'the means of maintaining British influence in the age of superpowers').15

By the time the Festival took place the British government had been forced to withdraw from Burma (which never became a Dominion and never became part of the Commonwealth), from Ceylon and, most significantly, from India. It was by no means the 'high point' of decolonisation in quantitative terms, but it was a time during which anxieties, as well as differences of opinion, over how to deal with it were apparent, and when disturbances and knock-on effects were clearly brewing elsewhere, in (for example) Malaya, Egypt, the Gold Coast and Kenya. By 1951 three of these were demanding Dominion status. Decolonisation and the augmentation of 'the Commonwealth' was a process which, as Wm. Roger Louis put it, the British state aimed to present 'to the public as a result of British policy' - so that imperial loss would appear to be happening as a result of overarching control rather than being seen to involve the British 'lurch[ing] from one crisis to the next'.16

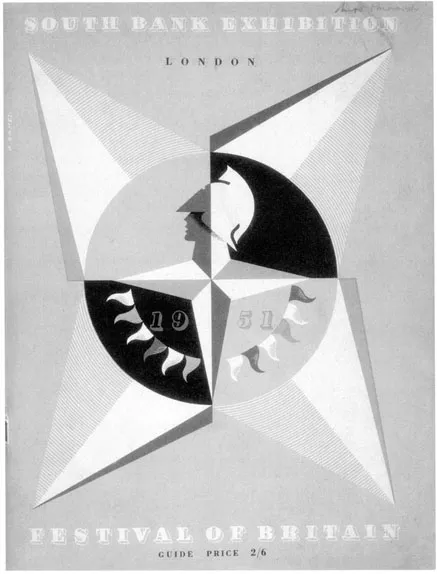

It is in relation to the tensions of this context that we can consider the discourse of continued imperial mastery. There was one very obvious and not particularly sublimated piece of imperial imagery at the Festival: Britannia. Britannia was made central to the entire celebration through her place in Abram Games's logo for the Festival of Britain, where she is in noble silhouette, her helmeted head firmly attached to a compass point, above festive bunting (Figure 1.1).17 As the personification of the country formed after the Roman invasion, Britannia had come to represent an idea of Britishness that was fashioned around white classical origins and imperial conquest. This idea was represented abstractly through the familiar trope of a woman as 'invulnerable epitome' of the nation rather than an image with which women were invited to identify.18

1.1 Abram Games's logo for the Festival of Britain as it appeared on the front cover of the Festival of Britain guidebook

In the Festival's main logo, then, the Britain being signified was an imperial nation. This has received remarkably little comment, mainly, I think, because the stark modernity of this iconography is not quite so readily associated with imperialism. As Bill Schwarz has pointed out, whilst it is easy to draw divisions between the style and politics of old imperial Britain and new consumer aesthetics at this time of decolonisation we also need to consider how memories of empire did not simply neatly disappear but could be reactivated in more modern environments.19 The logo is a perfect example of this, as imperialism is divested of some of its heavy grandiose swagger and portrayed instead through clean modern lines. The preliminary sketches for Games's initial design accentuated its militarism, being, to use his own description, 'starker'; the military helmet on Britannia's head was larger; and the sharp angles of the logo were more pronounced without the softening and more jaunty curves of the bunting that were added later. Games had previously worked for the Army Bureau, producing posters such as Your Britain - Fight for it Now!, and had been invited along with eleven other designers into the closed competition to invent a logo for the Festival. His design won the competition, and the Festival Committee asked him to soften its image a little in order to indicate the pleasurable and celebratory aspects of the Festival, exemplified by the Festival Pleasure Gardens in Battersea.20 The bunting was added; and so, replete with aesthetic reminders of white classicism and militarism, the imperial connotations of the logo were tempered through colour and curved lines.

Similarly, the brightly coloured space-age futurism of the South Bank site - represented most iconically through the Dome of Discovery and the Skylon - not only represented post-war relief and an aesthetic shift from an aesthetically monumental imperial tradition but also the continuation of some elements of imperialist expansionism. The Dome of Discovery included large murals by John Minton on the theme of 'Exploration' and by Keith Vaughan on 'Discovery', a large replica of Captain Cook's ship Endeavour, and a giant telescope.21 In the Festival's catalogue the Dome is described as the part rendering 'the distinctive British contribution' to the world complete. It acts as 'a memorandum on the pre-eminent achievements of British men and women in mapping and charting the globe, in exploring the heavens, and investigating the structure and nature of the universe'.22 And in an accompanying leaflet, visitors were told:

Here is told the resounding story of British discovery in all spheres - from the extrem[ity] of outer space down into the depth of the earth itself. Here it will be made plain how much of modern civilisation has sprung from these discoveries, and how the old spirit continues, the mantle of Drake being worn by the technologies and men of science today.23

Whilst the prosaic names given to sections of the Dome and other parts of the South Bank display (such as 'The Land' and 'The Living World') were, as William Feaver pointed out in 1976, 'a far cry from the lordly titles (The Grea...