![]()

PART I

The Administrator’s Role

![]()

1

The Principal Professional Learning Community

Principal inquiry is a process that allows me to do three things I need and like to do but rarely make time for: be a reflective practitioner, work with a true professional learning community, and model instructional leadership.

—Mike Delucas, Principal, Williston High School

Building a successful, powerful, systemwide professional development program must begin with a focus on administration. In order for teachers to experience powerful professional development at the building level, principals must understand and know what powerful job-embedded learning through inquiry looks and feels like. Yet, according to Roland Barth (2001),

Professional development for principals has been described as a “wasteland.” Principals take assorted courses at universities, attend episodic inservice activities within their school systems, and struggle to elevate professional literature to the top of the pile of papers on their desks. (p. 156)

Barth (2001) calls for districts to shift the ways they conceptualize principal professional development from answering the questions, “What should principals know and be able to do?” and “How can we get them to know and do it?” to “Under what conditions will school principals become committed, sustained, lifelong learners in their important work” (p. 157)? Building on the work of Roland Barth, this chapter introduces the cross-district principal professional learning community (PPLC) as a mechanism to support principals in becoming committed, sustained, lifelong learners.

WHAT IS A PPLC?

A PPLC is a small group of principals from across the district (typically about 5–10 people) who meet on a regular basis (usually as part of the district’s regularly scheduled administrative team meetings) to learn from practice through structured dialogue and engagement in continuous cycles of inquiry (articulating a wondering, collecting data to gain insights into the wondering, analyzing data, making improvements in practice based on what was learned, and sharing learning with others). PPLCs are an effective way for principals to reflect on their practice, set personal and school goals, develop a plan to achieve those goals, assess progress, and continue to grow professionally throughout their careers, all with the support of other professionals along the way.

There are two equally powerful ways the PPLC can function. First, a group of principals might share a common passion or dilemma about their practice as administrators and articulate and explore one collective wondering together.

A group of principals Carol and Sylvia worked with were frustrated with the way the classroom walk-through was playing out in their schools. Although they were going through all the motions of the classroom walk-through as they were taught to do during a districtwide inservice, this group of principals lamented that they, as well as their teachers, found little meaning in the process. They made a mutual commitment to formulate a learning community and work together to make the process of observation more meaningful to their work as administrators as well as for the teachers in their buildings. Together, they crafted one collective wondering that guided their inquiry: In what ways will focusing our classroom walk throughs on teacher-selected growth areas improve the walk-through process for us as administrators as well as for our teachers? Over several months, they worked together to create a plan to modify and enrich the classroom walk-through model. Their plan was informed by the literature on classroom walk throughs and teacher professional development, as well as data they collected at their school sites related to the ways teachers experienced the current classroom walk-through process. Sharing and discussing their data at learning community meetings led to further refinement and revision of the walk-through process for implementation the following school year, resulting in a much more effective implementation of the classroom walk-through in the eyes of the principals and their teachers.

Although principals often share a common dilemma they wish to explore (like making the classroom walk-through more meaningful and useful, as described above), frequently a principal faces complex issues specific to his or her school. Across a district, each principal functions within his or her own unique setting, serving diverse student populations and providing instructional leadership for faculties of teachers who vary in their teaching styles and personalities. Because of this variety, a principal may have burning individual questions that are critically important to that principal’s practice.

Hence, the second way a PPLC can function is as a sounding board in which each principal in the group can explore his or her own inquiry question. In this setting, the PPLC supports each principal through individual inquiry projects.

Nancy facilitated the work of a group of five principals from elementary, middle, and high schools in the same learning community. Each principal defined his or her own wondering to explore, and the group met about once a month to help each other develop their individual wonderings, develop a plan to collect data to gain insights into those wonderings, talk about how data collection was going, help each other analyze data once it was collected, and support each other in “packaging” their individual learning to share with others. The individual wonderings explored by this group of principals were as follows:

- What effect does the inclusion environment have on the reading achievement of eighth-grade language arts students at Lake Butler Middle School?

- In what ways will implementing the continuous improvement model help increase student achievement at my elementary school?

- In what ways are out-of-school or in-school suspensions as a consequence for discipline referrals affecting student performance?

- What actions can our faculty take to improve the reading achievement of our lowest quartile students?

- How does my teachers’ implementation of a purchased educational computer program relate to student learning?

The principals in this PPLC reported how much they learned not only from their own inquiries, but from the inquiries of their colleagues (Dana et al., 2010).

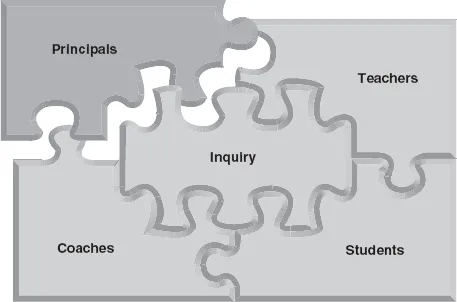

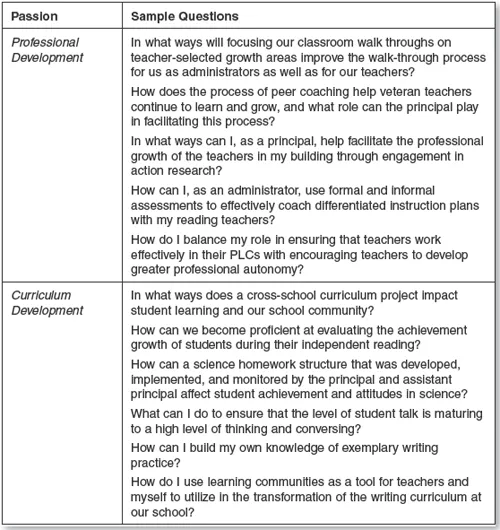

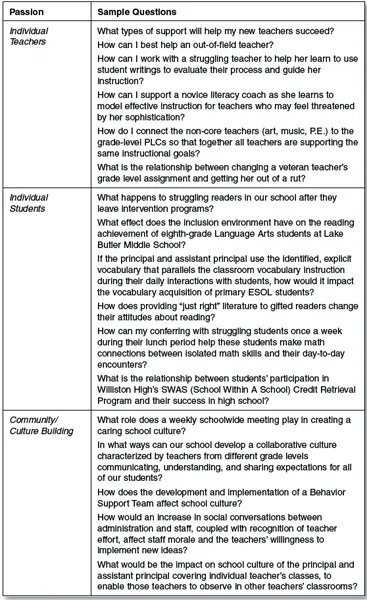

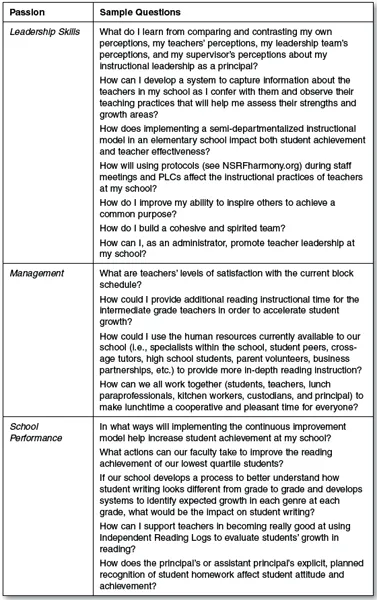

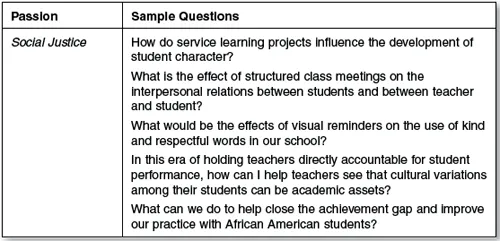

Regardless of the ways a PPLC functions (one collective wondering explored together as a group or each principal exploring individual wonderings and providing support for one another in their individual explorations), it is critical for the PPLC to define powerful questions to explore. The power of learning that occurs through the inquiry process can only be as good as the initial questions that frame the entire inquiry journey. Usually principal wonderings emerge from one of nine different passions central to the effective functioning of a school: professional development, curriculum development, individual teachers, individual students, school culture/community, leadership, management, school performance, or social justice. Figure 1.1 contains 50 examples of principal wonderings by passion.

Figure 1.1 50 Examples of Principal Wonderings by Passion

WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF PPLCS?

In addition to providing principals with a meaningful way to grow professionally, PPLCs provide other benefits to principals and their schools. There have been numerous discussions in the literature about teacher isolation that depict teaching as a lonely profession in which teachers close their classroom doors and have little interaction with other teachers in their buildings (see, e.g., Flinder, 1988; Lieberman & Miller, 1992; Lortie, 1975; Smith & Scott, 1990). If teaching is isolated, so too is the principalship.

Principals, just like teachers, need and treasure collegiality and peer support. Yet, perhaps even more than teachers, principals live in a world of isolation. Just as there is often distance for teachers between their adjoining classrooms, the distance across the district to another school is even greater. When principals associate with peers, it is often at an administrators’ meeting. In these infrequent and somewhat formal meetings, principals often feel that it is negatively stigmatized for them to admit to their peers that they do “not know” something. Neither the time nor the setting is conducive to collegial support or to the exchange of ideas and concerns. (Barth, 1990, p. 83)

In contrast, PPLCs provide an ideal setting for collegial support and the free exchange of ideas and concerns, taking principals out of isolation and into collaboration.

A second important benefit of PPLC work is that by engaging in this process, principals become role models for the teachers and students in their building. According to Roland Barth (1990), a precondition for realizing the extraordinary potential principals have to improve their schools is for them to become head learners.

Perhaps the most powerful reason for principals to be learners as well as leaders, to overcome the many impediments to their learning, is the extraordinary influence of modeling behavior. Do as I do, as well as I say, is a winning formula. If principals want students and teachers to take learning seriously, if they are interested in building a community of learners, they must not only be head teachers, headmasters, or instructional leaders. They must, above all, be head learners. I believe it was Ralph Waldo Emerson who once said that what you do speaks so loudly that no one can hear what you say. (p. 72)

Principal professional learning communities enable all principals across a district to become communities of head learners and do the important professional learning they advocate for their teachers, thereby modeling learning for teachers (and subsequently, students). On a related note, by engaging in PPLC work, principals experience what powerful, collaborative professional learning feels like, perhaps for one of the first times in their own careers as educators. Experiencing powerful, collaborative professional learning makes principals more likely and able to create the space and opportunity for meaningful, job-embedded, collaborative learning to occur among their teachers.

To illustrate, we turn to the three years of inquiry work of Monika Wolcott, an elementary school principal Carol and Sylvia worked with in Pinellas County Schools, Florida. During a recent annual districtwide inquiry celebration, where educators came together to share the results of their year-long research, Monika and several of her principal colleagues presented a collaborative group inquiry. Monika talked about the impact of inquiry on their collective learning.

WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES OF PPLC WORK?

At this point in the chapter, we would not be surprised if you were thinking, “Yeah, right! This all sounds wonderful, but can principals really find the time and make the commitment to meet with each other and study their practice?” It is normal and natural for principals to like the idea of meeting with a collaborative group of colleagues regularly and believe in the process of learning communities and inquiry in the abstract but protest a lack of time in their daily lives. Roland Barth (2001) informs us that one reason it is so difficult for school leaders to become learners is lack of time, but he reminds us, “For principals, as for all of us, protesting a lack of time is another way of saying other things are more important and perhaps more comfortable” (p. 157). To address the constraints of time, districts may consider rethinking the traditional “principal meeting format.” If principals are to become instructional leaders, then district leaders need to recognize the importance of collaboration and restructure their meetings to facilitate this type of interaction. Supervisors of principals send a powerful message to school-based leaders when they alter the format of the scheduled times principals come together to allow them time, on a regular basis, to collaborate and study their practice. When district leaders disseminate operational and organizational initiatives that are “information only” using e-mail or handouts, principals reduce the amount of time dedicated to “sit and get” and increase their opportunities to grow professionally in collaboration with their peers. Giving school-based leaders the gift of time for structured conversation and collegial support to investigate real-life dilemmas not only reinforces the notion that leaders must be learners but also sets the conditions so that principals see inquiry as part of their daily work.