![]()

Chapter One

Chronicles of Instrumentalists and Composers

During the late seventeenth century, from the rank-and-file instrumentalist to the maestro di cappella, nearly every kind of musician composed sonatas and dances. Individual profiles, however, reveal multiple appointments and activities, such that the ensemble instrumentalist and maestro sometimes came together in a single person who might have had other duties as well. Nor were published sonata composers necessarily professional musicians: young students of counterpoint (i.e., composition) and dilettante instrumentalists also contributed to the repertory.

The profile of Giuseppe Matteo Alberti (1685–1751), composer of a well-regarded set of concertos and of solo sonatas for the violin, is typical of the period.1 From 1709, he was violinist at S. Petronio. At different times over the course of his career, he also played violin in the church of S. Paolo Maggiore,2 directed concerts at the house of Count Orazio Bargellini (probably including duties as personnel manager of the musicians who participated),3 taught violin at the Bolognese Collegio de’ Nobili, and served as maestro di cappella at S. Giovanni in Monte and S. Domenico.4 He was therefore violinist, violin teacher, instrumental ensemble leader, and church music director. To give another example, Bartolomeo Bernardi (c.1660–1732), who published a collection each of church and chamber sonatas in the 1690s, pursued the single activity of church violinist, but did so in numerous places.5 According to the biographical entry for Bernardi in the Catalogo degli aggregati della Accademia Filarmonica, “he became by his musical virtues an instrumentalist in the illustrious cappella of S. Petronio and of S. Lucia and other churches. He also made himself heard in various important cities of Italy, clearly possessing a style that was serious and suitable to the church.”6

The likely reason why these two violinists worked as many jobs as they did is hinted in the pay records from S. Petronio.7 Laurenti was hired in 1669 at 8 lire (£) per month as the third violinist in the cappella musicale during Maurizio Cazzati’s tenure as maestro. In 1682, Laurenti was receiving £11.15 per month.8 By 1695, after 26 years’ service, he was earning £15, but the musical ensemble was disbanded in order to pay for repairs to the roof of the church.9 Over the next six years, he was hired on a per-service basis, earning, for example, £4.10 for the 1696 Mass and Vespers of All Saints’ Day and the Mass for All Souls’ Day.10 If he hadn’t already been doing so by this point, Laurenti must have started playing in other Bolognese churches and elsewhere outside of the city. Even after the musical ensemble of S. Petronio was reconstituted in 1701, he would have needed to continue outside work because his new salary was £5.15, a little over a third of his income in 1695 and less even than his beginning salary in 1669. Laurenti retired from S. Petronio in 1706 on the relatively fortunate terms of keeping that same £5.15 per month for life. However, to put those terms into further perspective, the maestro di cappella at that time, Giacomo Perti, was earning £50. Perti’s predecessor, Giovanni Paolo Colonna, earned around £75, and both of these salaries pale in comparison to the £120 per month earned by Cazzati, who preceded Colonna.

Alberti’s starting salary as violinist in 1709 is not recorded, but in 1715 it was £4, and during his time as violinist at S. Petronio until 1750 it never rose above £7. Salaries at S. Petronio were generally lower in the eighteenth century than they had been during the latter part of the seventeenth century, but even during the better-paying years, violinists rarely earned a lucrative sum. In addition to these musicians who had regular positions in a famous cappella musicale, others pursued less steady careers that are harder to reconstruct because they took place largely outside of institutions whose records survive. Domenico Marcheselli (d. 1703), a native of Bologna and member of the Accademia Filarmonica from 1681, was remembered as “skilled at balls while he was head violinist at the most sumptuous celebrations. He competed with the most diligent of his time.”11 Antonio Grimandi (d. 1731), also a Bolognese violinist and, from 1684, member of the Accademia Filarmonica, “was heard in the principal cities of Italy in both ecclesiastical and theatrical functions…. He also had various violin students, in both Bologna and Ferrara, who praise him.”12 Both performed in S. Petronio as sopranumerari (i.e., extra musicians for its larger feast-day ceremonies), receiving one lira per service, and both competed for a regular position there, but as far as is known, they made do in freelance careers that included teaching the violin, composing a few sonatas, and playing at churches, theaters, or balls in Bologna and elsewhere.

A handful of sonata composers were students or members of the nobility, or otherwise worked outside the musical profession. Tomaso Pegolotti, the author of a set of suites, described himself as “vicesegretario e cancelliere” (assistant secretary and chancellor) to Foresto d’Este, Marquis of Scandiano.13 Artemio Motta, a priest and member of a good family according to the historian Nestore Pelicelli,14 reveals nothing of himself in his published Concerti a cinque (1701), save that he was a native of Parma and, with a dedication in verse, that he wrote poetry. Francesco Giuseppe De Castro was a student at the Collegio de’ Nobili in Brescia when he published his Op. 1 dance suites, or as he characterizes them, the “first works, I would say, not of my study, but of my respite from the more rigorous and severe occupation of other studies.”15 Music, then, was a sideline to his principal studies. De Castro describes the priorities of his dedicatee, Gaetano Giovanelli, a Venetian count and fellow convittore at the Brescian collegio, in similar terms: “To him … wholly intent on the seriousness of philosophical studies and on the amenities of literature, the offering of a harmonic diversion, perhaps unseasoned, might seem an audacious importunity.”16 According to the plan of studies instituted in the Jesuit-run schools for the nobility, music, although diligently cultivated, amounted to a gentlemanly refinement outside the main curriculum of philosophy and literature.17 De Castro’s sonatas are thus a reflection of activities fostered as aristocratic diversions. The works of Pegolotti, an official under an important noble, and Motta, a cleric who delighted in writing in verse, may also represent the fruits of a gentleman’s extracurricular pursuits.

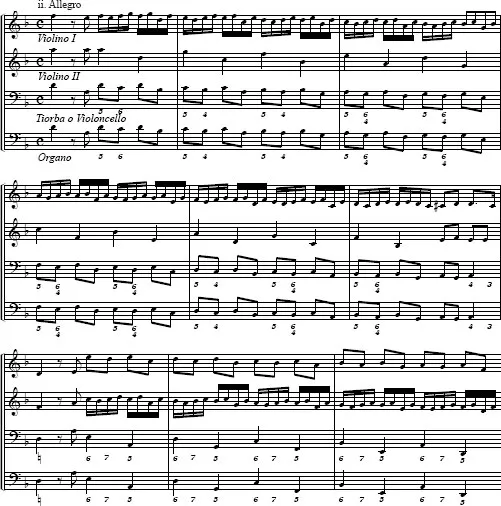

Less obscure and of higher social rank than these three composers is Pirro Albergati, who bore the title of count and belonged to one of Bologna’s senatorial families (see Figure 0.6, which shows a grand serenata held at their country estate).18 This may have afforded him a certain marketable cachet, at least in the eyes of Giacomo Monti, the music publisher, and Marino Silvani, Monti’s selling-agent. As mentioned in the introduction, Albergati’s first publication, a collection of dances printed in 1682, was the result of the publisher’s persuasions. And his second, an assortment of church sonatas, was printed the following year at the expense of (a spese di) Silvani.19 Was Albergati a marketable quantity at least partly because of his good social standing? Possibly. His Op. 1 dances would sell well enough to merit reprinting in a few years’ time, but his Op. 2 sonatas demonstrate an inconsistent talent. Albergati’s Op. 2, No. 5, for example, begins with a movement (Adagio, adagio) of inspired pathos (Example 1.1a), perhaps anticipating his later activity composing for the theater, but that conspicuous opening is followed by easily the most tedious movement in the Bolognese repertory—a lengthy Allegro in concertato style that comprises little more than a series of overextended sequences (Example 1.1b). The other non-professionals reveal a range of musical sophistication, from the simple-but-competent dance movements by De Castro (shown in Chapter 2 as Examples 2.2c and 2.2d) to the impressive violin suite in double-stops by Pegolotti (Chapter 2, Example 2.8b), so that it would be untenable to link professional standing with musical quality. Nonetheless, the inclusion of various non-professional as well as professional composers points up the music publishers’ efforts in building up a catalog of instrumental music by drawing on all available sources.

Example 1.1a P. Albergati, Op. 2, No. 5 (1683)

Example 1.1b P. Albergati, Op. 2, No. 5 (1683)

Instrumentalists and Patrons

The Bolognese market thus saw prints by composers from two broad classes of musician: the professional instrumentalist who pursued, often by financial necessity, a multifaceted career, and produced sonatas and dances as a byproduct of his playing circumstances; and the composer by avocation whose music for instrumental ensemble reflects the pursuits appropriate to a gentleman of the period. Among the professionals, music was often a family occupation, and in several cases blood relations were invoked in petitions for employment. Giulio Cesare Arresti, the son of a lutenist in the Concerto Palatino of Bologna, followed in his father’s footsteps there, beginning as a sopranumerario di liutista at the tender age of nine.20 He later won a position as organist at S. Petronio and had been first organist there for many years when he petitioned the vestry-board to name his own son, Floriano, as his replacement in the early 1690s:

Giulio Cesare Arresti, Bolognese citizen and most humble servant of Your Most Illustrious Lordships, reverently expresses to you that for nearly sixty years he has enjoyed the honor of serving as organist in the illustrious Collegiata of S. Petronio and now, being of a very advanced age—but, with the help of God, in perfect health—and having a son among others by the name of Floriano Maria who currently exercises the same profession of organist and composer … dares to request the infinite goodness of Your Most Illustrious Lordships for the substitution of this son in the above-named position of organist, and this so that the petitioner may have the consolation before he dies of seeing his son honored with the position that his father currently enjoys.21

Despite his father’s letter, Floriano never got the job,22 but other petitions on behalf of family members were successful. Nor was it unusual for a son, sometimes at a remarkably early age, to take up a position his father had just vacated. A father and two sons of the Degli Antonii family—Giovanni, Giovanni Battista, and Pietro—worked as musicians in the Concerto Palatino for several decades in the mid seventeenth century. In 1650, Giovanni Battista, age thirteen, was admitted as sopranumerario trombonist just after his father’s retirement as ordinario on that instrument, the son having performed an audition with the ensemble (from which his father recused himself) on recorder and trombone.23 Five years later Pietro, the younger son, joined as sopranumerario “after having been heard to play diverse instruments with every perfection and excellence.”24 He was sixteen at the time. Giovanni Battista Bassani was maestro di cappella at the Accademia della Morte in Ferrara when his son Paolo Antonio became organist there in 1691;25 Pietro Paolo Laurenti joined his father, Bartolomeo, as violinist at S. Petronio in 1692; and later, in 1707, Girolamo Nicolò Laurenti, another son of Bartolomeo, was also admitted as violinist there in the year his father retired from that job;26 and G. B. Vitali was vice-maestro di cappella at the court of Francesco II d’Este when his son, Tomaso Antonio, joined as a violinist in 1675 at no more than twelve years of age.27

The principal musical employers within the Bolognese orbit—that is, Bologna, Modena, and Ferrara—encompassed church, court, and civic institutions. In Bologna, the cappella musicale of S. Petronio regularly employed around a dozen instrumentalists (2–4 violins, 1–3 violas, violoncello, violone, 1–2 theorbos, 1–2 trombones, 2 organs) after Maurizio Cazzati’s arrival in 1657.28 The Concerto Palatino typically featured eight trumpets, eight piffari (cornetts and trombones), a harpist, lutenist, and drummer for its civic functions.29 In Ferrara, the competing Accademia dello Spirito Santo and Accademia della Morte each kept a salaried maestro di cappella and organist, and hired singers and instrumentalists, mostly strings, on a per-service basis for feast-day performances throughout the liturgical year.30 And in Modena, the cappella musicale of the cathedral and the ducal cappella of the Este court, with more than a dozen instrumentalists during the reign of Francesco II, were the largest musical employers in that city.31 That much accounts for most of the steady work, to which we may add seasonal theater work (opera and oratorio) and occasional performances for private accademie and feste patronized by the numerous local nobility.

Employment in this milieu was obtained with the support of that nobility. In Modena, the centralized duc...