eBook - ePub

Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles

Values, Design, Production and Consumption

- 415 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles

Values, Design, Production and Consumption

About this book

There is no doubt that the textile industry – the production of clothing, fabrics, thread, fibre and related products – plays a significant part in the global economy. It also frequently operates with disregard to its environmental and social impacts. The textile industry uses large quantities of water and outputs large quantities of waste. As for social aspects, many unskilled jobs have disappeared in regions that rely heavily on these industries. Another serious and still unresolved problem is the flexibility textile industry companies claim to need. Faced with fierce international competition, they are increasingly unable to offer job security. This is without even considering the informal-sector work proliferating both in developing and developed countries. Child labour persists within this sector despite growing pressure to halt it.Fashion demands continuous consumption. In seeking to own the latest trends consumers quickly come to regard their existing garments as inferior, if not useless. "Old" items become unwanted as quickly as new ones come into demand. This tendency towards disposability results in the increased use of resources and thus the accelerated accumulation of waste. It is obvious to many that current fashion industry practices are in direct competition with sustainability objectives; yet this is frequently overlooked as a pressing concern.It is, however, becoming apparent that there are social and ecological consequences to the current operation of the fashion industry: sustainability in the sector has been gaining attention in recent years from those who believe that it should be held accountable for the pressure it places on the individual, as well as its contribution to increases in consumption and waste disposal.This book takes a wide-screen approach to the topic, covering, among other issues: sustainability and business management in textile and fashion companies; value chain management; use of materials; sustainable production processes; fashion, needs and consumption; disposal; and innovation and design.The book will be essential reading for researchers and practitioners in the global fashion business.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles by Miguel Angel Gardetti, Ana Laura Torres, Miguel Angel Gardetti,Ana Laura Torres in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The systemic vision and the value chain in the textile and fashion industry

1

Slow fashion

Tailoring a strategic approach for sustainability

Carlotta Cataldi, Maureen Dickson and Crystal Grover

Co-founders, Slow Fashion Forward

Co-founders, Slow Fashion Forward

Instead of tackling ecological and social issues in the mainstream fashion industry by consulting with established, globalised fashion brands, solutions for sustainable fashion may be found in an alternative sector altogether, the slow fashion movement.

This chapter summarises the thesis ‘Slow Fashion: Tailoring a Strategic Approach towards Sustainability’ written collaboratively by Carlotta Cataldi, Maureen Dickson and Crystal Grover in 2010 during Master’s studies in Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability at the Blekinge Institute of Technology in Sweden. It outlines the strategic planning methods used in the research and proposes a set of recommendations that can serve as guidelines for established or emerging fashion professionals that are embarking on a sustainable business journey.

1.1 How can slow fashion help society to become more sustainable?

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete (Richard Buckminster Fuller).

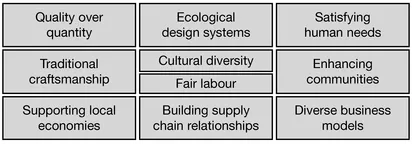

Slow fashion represents a new future vision for the fashion and textile industry, one where natural resources and labour are highly valued and respected. It aims to slow down the rate at which we withdraw materials from nature and acts to satisfy fundamental human needs. In this movement, the people who design, produce and consume garments are reconsidering the impacts of choosing quantity over quality; and redesigning ways to create, consume and relate to fashion.

The slow movements began to emerge in the late 1980s with Slow Food, a movement born in Italy with the purpose of preserving the cultural integrity of cuisine in local regions.1 The term ‘slow fashion’ was first coined by Kate Fletcher and shares many characteristics with the Slow Food movement (Fletcher 2007).

The slow approach allows for quality design and production to emerge, with high regard for the garment-making process and its relationship with the human and natural resources on which it depends. Slow fashion includes many diverse business models that maintain profits, while conserving and enhancing our ecological and social systems.

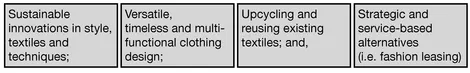

To conserve and protect the natural resources being consumed globally by the fashion industry, the slow fashion movement promotes:

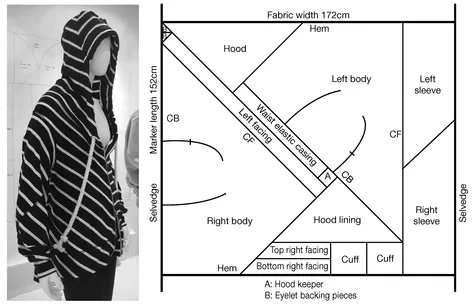

For example, Timo Rissanen’s ‘jigsaw puzzle’ method (Fig. 1.1) uses all pieces of the garment pattern in the final design (McQuillan 2011). Upcycling vintage and reclaimed materials is another strategy for slowing down consumption and extending the lifespan of existing materials.

Slow fashion organisations may also support local communities and economies by sourcing materials and labour locally. Pact, an underwear brand, ensures that the organic cotton crop, its processing, spinning, knitting, weaving, dyeing, printing and sewing happen within the same 100-mile radius in Turkey. Some initiatives get right to the heart of resourcefulness, such as Our Social Fabric, a community-based textile-sourcing initiative in Vancouver. While, Remade in Leeds teaches locals sewing skills and makes new clothes from castoffs.2

Many brands also invest in communities for the long term and aim to help catalyse social change in locales where operations take place; for example, Oliberté, a footwear brand, has set up production in Africa with the goal of providing sustainable employment for the growing middle class (GOOD 2012).

The slow fashion movement is also working to preserve traditional garment-making skills rooted in cultural heritage. The fashion industry can look to the past, and has a responsibility and opportunity to carry forward these traditional techniques into future generations. The Permacouture Institute has initiated a fibre and dye mapping project and seed saving to preserve biodiversity in textile fibres and dye plants.

Figure 1.1 Timo Rissanen’s No Waste Hoodie

In the slow fashion movement, garment workers are paid a living wage and provided with safe and healthy working conditions. Slow fashion aims to improve the quality of life for people in and affected by the fashion industry and examines all aspects of the garment life-cycle: from fibre harvesting to disposal.

A defining trait of the slow fashion movement is that it recognises the evolving fashion needs of ‘New Consumers’ (BBMG 2011). New Consumers make more conscious choices that support a sustainable future by slowing down to discover how and where garments are made, and learn about minimising their consumer impacts. Whenever possible, responsible actions are taken to be creative and skilful, by consuming less, restyling garments, swapping clothing or supporting sustainably sourced and locally made fashion.

Slow fashion has the capacity to support the human needs of every person across the entire supply chain, with more opportunities to participate, express, create and innovate sustainably.

1.2 The fashion industry as a system

We live in a world of complex systems. Organisms, ecosystems, factories, families, cities and even the Earth itself are all complex systems. A system is an organised collection of parts that are highly integrated to accomplish an overall goal.

When making decisions and operating in a complex system, like the fashion industry, it can be useful to imagine that we are birds soaring above it. Gaining perspective of the global fashion system we can see its parts and the connections between them, and understand the greater impacts that fashion production and consumption have on society and ecological systems. From the raw fibres such as cotton, wool and silk, harvested across geographies, the millions of garment workers labouring in factories, to the independent designers cutting patterns, and the final garment that clothes an individual for a lifetime. These connections across the fashion supply chain and beyond to the garment wearer are encompassed in the larger fashion system.

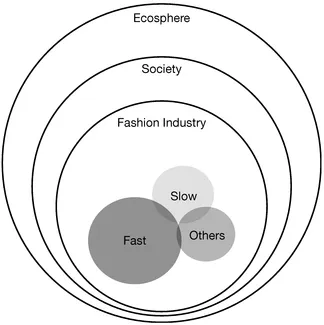

We can visualise the fashion industry as being composed of smaller systems, such as the mainstream ‘fast fashion’ industry, the emerging slow fashion movement, and others, such as haute couture (see Fig. 1.2). In this chapter, slow fashion gathers a number of business models and fashion industry terms, such as sustainable new, eco fashion, ethical fashion, locally made, vintage and second-hand, under one unified movement.3

Every action carried out collectively by one system, such as fast fashion, or another one, such as slow fashion, will have an impact on the whole. This way of thinking can help understand the overall structure of the fashion system, the patterns and the cycles present in it, and it can facilitate the identification of the root causes of problems, showing the interconnectivity between events, and suggesting the most strategic ways to create solutions.

It also highlights the dependence of our society and the fashion industry on the ecosphere: natural resources such as clean water, land, air, fossil fuels and raw fibres, as well as ecological biodiversity (see Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The fashion industry as a system

1.3 Fashion and human needs

The use and consumption of material goods, including fashion, is correlated to the attempt of individuals to meet their human needs, which are an intrinsic part of human nature. Satisfying these needs can help people to have emotionally rich, healthy lives (Max-Neef 1991). Several people have proposed different classifications of human needs, but the theory of Chilean economist, Manfred Max-Neef, is the most comprehensive as it considers nine human needs organised in a nonhierarchical way (see Table 1.1). These are the same for everyone, regardless of culture, religion or historical time.

Each person can satisfy their needs in different ways. Max-Neef calls these ‘satisfiers’. Fashion can act as a satisfier for the needs of subsistence and protection, which tend to require a minimum level of material input. It also acts as a satisfier for the needs of identity, creation and participation, which could theoretically be satisfied by participatory processes (personal, social and cultural) rather than by consumption of fashion goods (Jackson and Marks 1994).

Table 1.1 Basic human needs

| 9 Human needs | ||

| Subsistence | Protection | Participation |

| Idleness | Creation | Affection |

| Understanding | Identity | Freedom |

Source: Adapted from Max-Neef 1991

1.4 A closer look at fast fashion

The primary purpose of ‘fast fashion’ is to accelerate consumption of trend-driven clothing, while maximising profits for a limited number of globalised megabrands. From a positive perspective, fast fashion allows millions of people to purchase clothing at affordable prices, making it possible for low-income families as well as young adults to access the latest runway trends, improving feelings of belonging and well-being. The global fashion industry is also a driver of economic growth and employs 26 million people worldwide (Allwood et al. 2006).

This business model has its trade-offs. Garments are being sold at very low retail prices, which encourages consumers to purchase more than they need. The price also discounts the true external environmental and social costs of producing the garment. The news of child labour in the cotton fields of Uzbekistan and Burkina Faso and the extremely low wages and unpaid overtime in thousands of factories in developing countries are making it evident that, as a system, fast fashion is capable of hindering the ability of millions of people worldwide to meet some of their fundamental human needs.

Today’s fashion scenario, characterised by mass-produced, throwaway fashion, has also decreased the capacity for consumers to satisfy their human needs. Fast fashion promotes trends that dress consumers all over the world, producing a homogeneous look that is unlikely to satisfy, for example, the needs of identity and creativity. As a society, we are also losing the most basic garment-making and repair skills, since skills are decreasing in value in a world where garments are cheap and disposable. Above all, it disconnects the consumer from the process of garment making, limiting the feeling of participation. In this way, we can say that mainstream fast fashion is a pseudo-satisfier to a number of human needs.

1.5 Today’s sustainability challenge and the fashion industry

The mainstream fashion industry is contributing to today’s sustainability challenge in a number of ways. Thanks to the many publications released by research centres and NGOs, and the increasing visibility these topics are gaining in media, the industry is more aware of the important impacts that fashion production and consumption have on ecological and social systems.

Due to increasing consumer demand for fast fashion, the fashion industry currently uses a constant flow of natural resources to supply this demand. The current operation of the fashion industry is consistently contributing to the depletion of fossil fuels in textile and garment production and transportation (Allwood et al. 2006). Fresh water reservoirs are also being increasingly diminished for cotton crop irrigation; one significant example is the depletion of the Aral Sea (Draper et al. 2007; Environmental Justice Foundation 2010). The fashion industry is introducing in a systematic way, and in greater amounts, man-made compounds such as pesticides and synthetic fibres, which have a persistent presence in nature (Claudio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: The systemic vision and the value chain in the textile and fashion industry

- PART II: Marketing, brands and regulatory aspects in the textile and fashion industry

- PART III: The practice in textiles and fashion

- PART IV: Consumer: purchase, identity, use and care of clothing and textiles

- Index