- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Methods in Practical Laboratory Bacteriology

About this book

The success of laboratory experiments relies heavily on the technical ability of the bench scientist, with the aid of "tricks-of-the-trade", to generate consistent and reliable data. Regrettably, however, these invaluable "tricks-of-the-trade" are frequently omitted from scientific publications. This paucity of practical information relating to the conduct of laboratory bacteriology experiments creates a gaping void in the pertinent literature.

Methods in Practical Laboratory Bacteriology fills this void. It provides detailed technical information that ensures that you achieve consistent and reliable data. The book addresses the aspects of bacterial fractionation and membrane characterization, the analysis of Lipopolysaccharides and the techniques of SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and ELISA. It also describes the methods used for detecting and quantifying bacterial resistance to antibiotics, and the analysis of bacterial chromosomes by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Methods in Practical Laboratory Bacteriology also covers protocols for extracting the fingerprinting plasmids, as well as the use of non-radio labeled gene probes and ribosomal RNA gene probes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | BACTERIAL FRACTIONATION AND MEMBRANE PROTEIN CHARACTERIZATION |

I. | Introduction | |

II. | Cellular Fractionation | |

A. | Materials | |

B. | Methods | |

C. | Results | |

III. | Outer-Membrane Characterization | |

A. | Heat-Modifiable Proteins | |

B. | Peptidoglycan-Associated Proteins | |

IV. | Membrane-Associated Proteins | |

A. | Fimbriae and Flagella | |

B. | Membrane-Associated Proteins | |

V. | Isolation of Proteins from SDS-PAGE Gels | |

A. | Materials | |

B. | Methods | |

VI. | Troubleshooting | |

Appendix | ||

References | ||

I ▬ INTRODUCTION

The reasons for fractionating bacteria into subcellular components are many and varied and range from those relating to pure research with the aim of gaining a better understanding of detailed aspects of bacterial cell biochemistry, to those concerning strain discrimination for epidemiological studies of bacterial diseases. The methods used for cellular fractionation will depend on the basic structure of the bacteria under investigation.

In their most basic structural form, bacteria comprise a protein-lipid envelope surrounding a cell cytoplasm, and with the exception of the more unusual bacteria, for example, Mycobacteria and Rickettsia, most species can be divided into those which possess an outer membrane and those which do not. A method for discriminating these two classes of bacteria has been known for over a century in the form of the Gram-stain, which divides bacteria into either Gram-negative (with an outer membrane) and Gram-positive. However, it was only comparatively recently that the basis for the staining reaction was shown to involve the staining of one particular part of the bacteria cell, the peptidoglycan. Peptidoglycan forms a structural lattice,1 which surrounds the inner membrane and is sandwiched between the inner and outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. In the absence of an outer membrane, Gram-positive bacteria retain the stain (crystal violet) and appear blue under the light microscope, while Gram-negative bacteria do not retain crystal violet stain and can only be seen by light microscopy if stained with an alternative stain such as safranine.

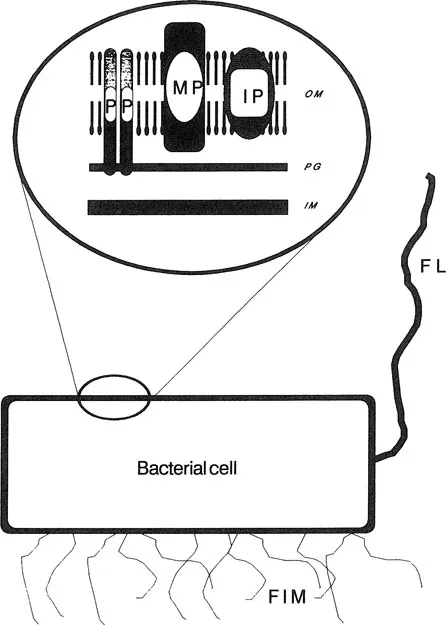

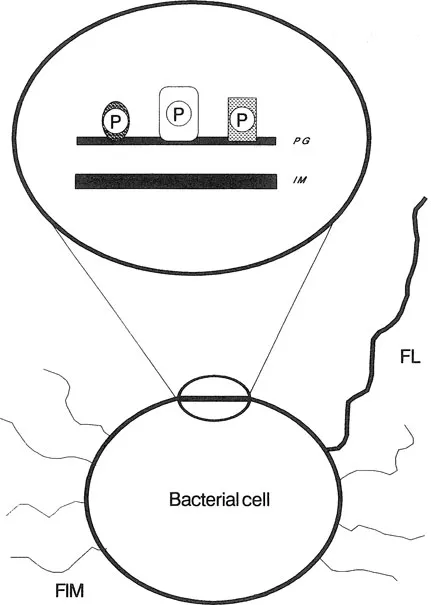

In general, Gram-negative bacteria have a more complicated envelope structure than Gram-positive bacteria. The outer membrane contains various outer membrane proteins, some of which are linked noncovalently to peptidoglycan (Figure 1). Gram-negative bacteria also differ from Gram-positive bacteria by expressing surface-exposed carbohydrate structures termed lipopolysaccharides (LPS), also called the endotoxin portion of bacteria (see Chapter 2). In contrast, the cell envelope of Gram-positive bacteria does not contain LPS (Figure 2).

The bacterial cell envelope forms a physical barrier between the cytoplasm and the external environment. This membrane contains all the components involved in the binding and translocation of elements required for bacterial biochemistry (Table 1). The cell envelope also contains many of the structures associated with pathogenicity, such as fimbriae and the organelles of motility, the flagellae (Figures 1 and 2). Certain membrane components, such as the structural peptidoglycan and the general pore-forming proteins (involved in the passage of molecules through the outer membrane), are expressed regardless of the bacterial environment and are consequently termed “constitutive” (Table 1). However, other bacterial components are expressed only under special environmental conditions and are termed “inducible” (Table 2). Examples of inducible proteins are those involved in the high-affinity acquisition of iron and the uptake of phosphate and vitamin B12 (see Table 1 and Chapter 6).

When examining bacterial proteins, it should always be borne in mind that the expression of certain proteins may relate to the availability of specific broth constituents or may depend on changes in media composition during the growth cycle. For these reasons it is important to be consistent in the way bacteria are grown, paying particular attention to consistency in culture media used and in incubation times employed.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria. The outer membrane (OM) is comprised of a lipid bilayer surrounding a layer of peptidoglycan (PG), which in turn covers the inner membrane (IM). The outer membrane contains the major proteins (MP), the peptidoglycan-associated, pore-forming proteins (P) and inducible proteins, and transmembrane pore proteins, in addition to several minor proteins. Certain bacterial species may also express flagella (FL) and fimbriae (FIM).

Figure 2 Schematic representation of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. The layer of peptidoglycan (PG), which surrounds the inner membrane (IM), is attached to various proteins (P). Certain bacterial species may also express flagella (FL) and fimbriae (FIM).

Certain proteins have distinct biochemical properties that can be exploited when characterizing cellular proteins. For example, pore-forming proteins exist in the cell envelope as macromolecular complexes which denature on heating (heat modifiable) to form heat-stable protein subunits. Also, protein structures attached to the cell surface, such as flagella and fimbriae, can be removed from bacteria with minimal damage to the bacterial cell envelope.

This chapter describes some basic procedures for the fractionation, identification, and characterization of certain bacterial envelope proteins. As with all experiments involving bacteria, protocols may need to be modified to suit the organism under investigation. Some of the procedures used to investigate bacterial cell envelope proteins may also isolate membrane-associated proteins such as flagella, fimbriae, and extracellular protein layers (Table 1). Methods for examining bacteria for these membrane-associated proteins will also be described. For more information relating to bacterial outer-membrane proteins, the reader is referred to selected reviews.2,3

As studies of bacterial membranes progressed over the years, the various component parts were identified and allocated names. As a result many of the same membrane proteins were given different names which regrettably created considerable confusion in the nomenclature used for these proteins. An excellent review4 has succeeded in unraveling the confusion and should be consulted before delving into historical literature.

TABLE 1

EXAMPLES OF OUTER MEMBRANE PROTEINS EXPRESSED BY BACTERIA

Protein | Role |

Lipoprotein (7.2 kDa) | Anchoring outer-membrane proteins to peptidoglycan |

OMP A (33–35 kDa) | Has limited pore-forming properties, not peptidoglycan associated |

OMP C (36–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

OMP E | Pore-forming protein? |

OMP F (37–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

OMP D (34–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

Phage T6 receptor (26 kDa) | Uptake of nucleosides |

M protein (30–180 kDa) | Expressed by streptococci, confers protection against host defense mechanisms |

Protein A (42 kDa) | Binds Fc portion of antibodies, other than IgM, preventing specific antibody binding (see Glossary) |

TABLE 2

EXAMPLES OF INDUCIBLE BACTERIAL PROTEINS

Protein | Growth Conditions causing Expression | Role |

PHO E (37–40 kDa) | Phosphate limitation | Pore for uptake of polyphosphates |

LAM B 47–50 kDa) | Presence of maltose | Pore for uptake of maltose and maltodexrins |

BTU B (60 kDa) | Vitamin B12 | Uptake of vitamin B12 |

CIR (74 kDa) | F... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- How to Use This Book

- 1 Bacterial Fractionation and Membrane Protein Characterization

- 2 Lipopolysaccharide: Isolation and Characterization

- 3 Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis for the Separation and Resolution of Bacterial Components

- 4 Reaction of Antibodies with Bacterial Components using Immunoblotting

- 5 The Use of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay in Bacteriology

- 6 Environmental Regulation of Bacterial Characteristics: The Availability of Iron

- 7 Testing for Resistance to Antimicrobial Drugs

- 8 Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis of Bacterial DNA

- 9 Extraction and Fingerprinting of Bacterial Plasmids

- 10 Nonradioactive Digoxigenin-Labeled DNA Probes

- 11 Ribotyping of Bacterial Genomes

- Sources of Equipment and Chemicals

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Methods in Practical Laboratory Bacteriology by Henrik Chart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.