![]()

1 | BACTERIAL FRACTIONATION AND MEMBRANE PROTEIN CHARACTERIZATION Henrik Chart |

| | |

I. | Introduction |

II. | Cellular Fractionation |

| A. | Materials |

| B. | Methods |

| C. | Results |

III. | Outer-Membrane Characterization |

| A. | Heat-Modifiable Proteins |

| B. | Peptidoglycan-Associated Proteins |

IV. | Membrane-Associated Proteins |

| A. | Fimbriae and Flagella |

| B. | Membrane-Associated Proteins |

V. | Isolation of Proteins from SDS-PAGE Gels |

| A. | Materials |

| B. | Methods |

VI. | Troubleshooting |

Appendix |

References |

I ▬ INTRODUCTION

The reasons for fractionating bacteria into subcellular components are many and varied and range from those relating to pure research with the aim of gaining a better understanding of detailed aspects of bacterial cell biochemistry, to those concerning strain discrimination for epidemiological studies of bacterial diseases. The methods used for cellular fractionation will depend on the basic structure of the bacteria under investigation.

In their most basic structural form, bacteria comprise a protein-lipid envelope surrounding a cell cytoplasm, and with the exception of the more unusual bacteria, for example, Mycobacteria and Rickettsia, most species can be divided into those which possess an outer membrane and those which do not. A method for discriminating these two classes of bacteria has been known for over a century in the form of the Gram-stain, which divides bacteria into either Gram-negative (with an outer membrane) and Gram-positive. However, it was only comparatively recently that the basis for the staining reaction was shown to involve the staining of one particular part of the bacteria cell, the peptidoglycan. Peptidoglycan forms a structural lattice,1 which surrounds the inner membrane and is sandwiched between the inner and outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. In the absence of an outer membrane, Gram-positive bacteria retain the stain (crystal violet) and appear blue under the light microscope, while Gram-negative bacteria do not retain crystal violet stain and can only be seen by light microscopy if stained with an alternative stain such as safranine.

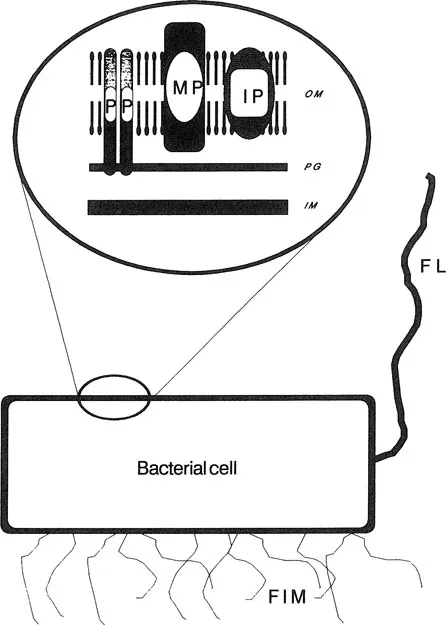

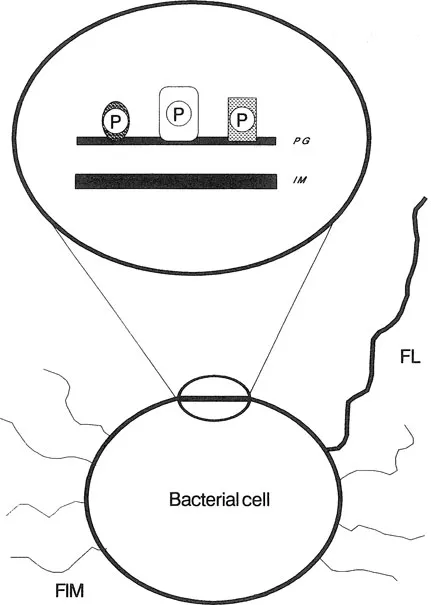

In general, Gram-negative bacteria have a more complicated envelope structure than Gram-positive bacteria. The outer membrane contains various outer membrane proteins, some of which are linked noncovalently to peptidoglycan (Figure 1). Gram-negative bacteria also differ from Gram-positive bacteria by expressing surface-exposed carbohydrate structures termed lipopolysaccharides (LPS), also called the endotoxin portion of bacteria (see Chapter 2). In contrast, the cell envelope of Gram-positive bacteria does not contain LPS (Figure 2).

The bacterial cell envelope forms a physical barrier between the cytoplasm and the external environment. This membrane contains all the components involved in the binding and translocation of elements required for bacterial biochemistry (Table 1). The cell envelope also contains many of the structures associated with pathogenicity, such as fimbriae and the organelles of motility, the flagellae (Figures 1 and 2). Certain membrane components, such as the structural peptidoglycan and the general pore-forming proteins (involved in the passage of molecules through the outer membrane), are expressed regardless of the bacterial environment and are consequently termed “constitutive” (Table 1). However, other bacterial components are expressed only under special environmental conditions and are termed “inducible” (Table 2). Examples of inducible proteins are those involved in the high-affinity acquisition of iron and the uptake of phosphate and vitamin B12 (see Table 1 and Chapter 6).

When examining bacterial proteins, it should always be borne in mind that the expression of certain proteins may relate to the availability of specific broth constituents or may depend on changes in media composition during the growth cycle. For these reasons it is important to be consistent in the way bacteria are grown, paying particular attention to consistency in culture media used and in incubation times employed.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria. The outer membrane (OM) is comprised of a lipid bilayer surrounding a layer of peptidoglycan (PG), which in turn covers the inner membrane (IM). The outer membrane contains the major proteins (MP), the peptidoglycan-associated, pore-forming proteins (P) and inducible proteins, and transmembrane pore proteins, in addition to several minor proteins. Certain bacterial species may also express flagella (FL) and fimbriae (FIM).

Figure 2 Schematic representation of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. The layer of peptidoglycan (PG), which surrounds the inner membrane (IM), is attached to various proteins (P). Certain bacterial species may also express flagella (FL) and fimbriae (FIM).

Certain proteins have distinct biochemical properties that can be exploited when characterizing cellular proteins. For example, pore-forming proteins exist in the cell envelope as macromolecular complexes which denature on heating (heat modifiable) to form heat-stable protein subunits. Also, protein structures attached to the cell surface, such as flagella and fimbriae, can be removed from bacteria with minimal damage to the bacterial cell envelope.

This chapter describes some basic procedures for the fractionation, identification, and characterization of certain bacterial envelope proteins. As with all experiments involving bacteria, protocols may need to be modified to suit the organism under investigation. Some of the procedures used to investigate bacterial cell envelope proteins may also isolate membrane-associated proteins such as flagella, fimbriae, and extracellular protein layers (Table 1). Methods for examining bacteria for these membrane-associated proteins will also be described. For more information relating to bacterial outer-membrane proteins, the reader is referred to selected reviews.2,3

As studies of bacterial membranes progressed over the years, the various component parts were identified and allocated names. As a result many of the same membrane proteins were given different names which regrettably created considerable confusion in the nomenclature used for these proteins. An excellent review4 has succeeded in unraveling the confusion and should be consulted before delving into historical literature.

TABLE 1

EXAMPLES OF OUTER MEMBRANE PROTEINS EXPRESSED BY BACTERIA

Protein | Role |

Lipoprotein (7.2 kDa) | Anchoring outer-membrane proteins to peptidoglycan |

OMP A (33–35 kDa) | Has limited pore-forming properties, not peptidoglycan associated |

OMP C (36–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

OMP E | Pore-forming protein? |

OMP F (37–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

OMP D (34–38 kDa) | General pore for hydrophilic solutes |

Phage T6 receptor (26 kDa) | Uptake of nucleosides |

M protein (30–180 kDa) | Expressed by streptococci, confers protection against host defense mechanisms |

Protein A (42 kDa) | Binds Fc portion of antibodies, other than IgM, preventing specific antibody binding (see Glossary) |

TABLE 2

EXAMPLES OF INDUCIBLE BACTERIAL PROTEINS

Protein | Growth Conditions causing Expression | Role |

PHO E (37–40 kDa) | Phosphate limitation | Pore for uptake of polyphosphates |

LAM B 47–50 kDa) | Presence of maltose | Pore for uptake of maltose and maltodexrins |

BTU B (60 kDa) | Vitamin B12 | Uptake of vitamin B12 |

CIR (74 kDa) | F... |