![]()

Interlude

Pilates

Pilates is my latest battle plan. Not wanting to go gentle, I have decided that Joseph’s plan to rehabilitate mere boys wounded on the European battlefields during World War 1 might slow time’s winged chariot.

On my way to the Rathdowne Street rooms with Radio National as my preferred background noise, I crawled through the intersection of Elgin Street and Lygon Street.

“What are your five favourite albums, James?” enquired the radio broadcaster of her guest, James Morrison, an iconic Australian musician. I adjusted the volume wondering which other trumpeters the jazz virtuoso would land on. The story unfolded. Forgive me for I will paraphrase; search the RN website, as I have; I couldn’t get a transcript. Anyway, stories usually improve as they wander away from their source.

James Morrison demurred and instead of selecting five tracks as he has done before, he opted for one album. He told the story of how as an 11-year-old he first heard Errol Garner’s Concert by the Sea. He spoke of how the trio comprising Errol Garner (piano), Eddie Calhoun (bass) and Denzel Best (drums) drove to a church hall in Carmel, California, on 19 September 1955 to play an afternoon gig. Not an important gig in prospect. Someone had recorded them on a primitive tape recorder and from that the album was born. For James Morrison, the album captures and communicates the mystery of a live performance where there is some kind of alchemy that connects musicians each to the other as well as the musicians and the audience to each other in a performative communion. The recording resonates that chemistry; that musical congress.

As someone who has fumbled his way through gigs with friends, I have felt occasions where there is that union between musicians and audience, each understanding and delighting in their imperfect achievement in sound. James described that with reference to Errol Garner’s Carmel recording. The quality and achievement of the music on that day 62 years ago in that place depended upon a fusion of all of the elements: the virtuosity of the musicians and their sensibility of each other; the readiness, enthusiasm and knowledge of the audience; and the spirit of place. The musicians and audience bring their differences to the venue and respectfully seal a pledge to meld these differences to enact the music.

Finding that unity of purpose within the complex amalgam of elements that constitutes an inclusive school seems to be a rare achievement. How to capture such a performance? Jazz musicians are schooled formally and informally to hone their craft. How to school our educators and a school community for inclusion? How to realise that the differences between the players and the interplay and union of those differences actually constitutes the magic? What would your music teacher or mentor tell you? It may go like this: select the challenging score, practice every day by yourself and regularly with your combo. Talk about the score and your playing. Seek differences to build greater possibility. Record and listen (no, really listen) and push each other to get it right. And make sure that you all retain fun and enjoyment throughout.

![]()

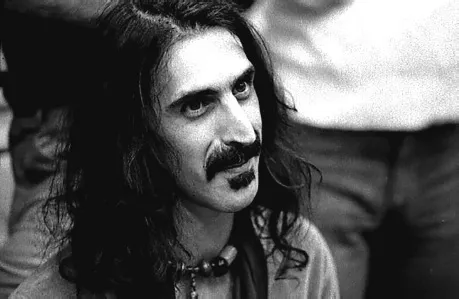

1 A time for Frank speaking

Frank Zappa left this world too soon, dying at the age of 52. His musical legacy, comprising some of the most complicated polyrhythms and atonal soundscapes, is immense. He left us much more. Some of his onstage remarks, retorts in interviews and his writing, are now iconic. They are often referenced in work on almost any subject. Let me join that tradition as a way of commencing this essay.

In his autobiography entitled The Real Frank Zappa Book,1 he opens one section with the heading: Jazz: The Music of Unemployment. His relationship with jazz was enigmatic as musicologist Geoff Wills2 demonstrates with forensic zeal. While Zappa declared his disdain for jazz, in the various incarnations of his bands and orchestras, most notably The Mothers of Invention, he surrounded himself with musicians with stellar jazz pedigrees. A quick and incomplete roll call includes: Bruce, Tom and Walter Fowler, Ruth and Ian Underwood, Gary Barone, Jean Luc Ponty, George Duke, John Guerin, Allan Zavod, Vinnie Colaiuta, Chester Thompson, Chad Wackerman and Jay Migliori. Moreover, his music embraced many genres within the jazz family. How could Hot Rats be heard as anything but a highly derivative and delightful achievement in jazz? Listen to the album Roxy and Elsewhere and you will hear Zappa tell the audience that: “Jazz is not dead … it just smells funny”. For devotees of Zappa and of jazz, the quote is amusing yet perplexing.

My take on this quote from Zappa involves two explanations. The first is that he was characteristically prodding the lion of respectability with the broomstick of irreverence. It was just a humorous provocation that he really hadn’t thought about too much. Second, and more plausibly, he might be saying that all artistic genres go through a similar cycle: they confront what has gone before, offering up something that is apparently radical, innovative, new. And then, they become respectable and predictable. With age – vitality recedes; the aroma of adrenaline is replaced by the stench of atrophy. I watched an interview on Canadian television with jazz saxophonist Branford Marsalis who spoke of committing Bach’s 186 rules of harmony to memory before breaking them. “Whose rules”, he asked, “did Bach break when he established the canon?” Today’s radical utterances, like yesterday’s, morph into tomorrow’s conservatism.

John Gennari commences his text on jazz and its critics3 by declaring that his interest in jazz and the reportage that surrounds it arose “in the late 1970s (when) word of jazz’s death was all around”. I suspect that Zappa too was responding to the talk of the time, but with his own seriously humorous inflection that as “a cornerstone of modern cultural imagination”,4 jazz would again seed the confronting new sounds that would set in train a challenging progressive genre. Some may postulate that this was Zappa’s intent.

I am not breaking new ground here. In Reflections on Exile Edward Said presents an elegant essay entitled “Travelling Theory Reconsidered”5 wherein he reminds us that by the time Georg Lukas’s theory of reification was adopted by Lucien Goldman in Paris and Raymond Williams in Cambridge it had lost its “original power and rebelliousness”. Theories born from and organically linked to, historical circumstances are “degraded and subdued” by the passage of time and changing circumstances. They become a “relatively tame academic substitute for the real thing” whose essential purpose was disruption culminating in political change.

Previously I have registered my view that inclusive education is nearing exhaustion from its extensive global and trans-paradigmatic travels. Contemporary theories of inclusive education, to paraphrase Said, have largely been tamed and domesticated – thereby losing their insurrectionary zeal. I say theories because there is no general theory of inclusive education. It could be described as an assembly hall within which gather disparate and desperate postulations and propositions about the intersections of human and social pathology with education. Almost a decade ago Julie Allan and I described inclusive education as a “troubled and troubling” field of education research housing highly charged, often emotive and personalised, contests.6 Nothing seems to have changed. Or has it? The reluctant acceptance of inclusive education as an organising mantra has not prompted an interrogation of the “essence of exclusion”, the smelly side of schooling, or a will to change the fundamental settings that forms and rejuvenates it.

What are our options then? Capitulation? Inclusive education could dig its hands deep into its pockets, lower its head and shuffle off exhausted by attempts to resist the comfortable co-dependence of regular and special education. The near perfect attempt to silence inclusive education through the colonisation of its language and new franchising deals with units and classrooms in the neighbourhood school diminishes inclusive education’s original manifesto of justice for children and young people with disabilities.

Retreat will not do. An unobstructed triumph of exclusion is not really an option. Rather than abandon inclusive education and look for the next set of words with which to mount the battle against the exclusion of vulnerable population groups, let us go back to first principles and apply them to the changed and ever-changing circumstances of this liquid twenty-first century where commitment is illusory. This is the book’s hoarse whisper of hope that may simply be grasping at another opportunity to fail better.7

Them bones, them bones

I commenced this book with the proposition that exclusion resides deep in the bones of education; now is the time for explication. This really isn’t a hard case to put together. Education, as Connell counselled almost a quarter of a century ago, “is not simply a mirror of social or cultural inequalities”. “That”, she says, “is all too still an image. Education systems are busy institutions. They are vibrantly involved in the production of social hierarchies. They select and exclude their own clients; they expand credentialed labour markets; they produce and disseminate particular kinds of knowledge to particular users”.8 Connell, like others in what was then called the New Sociology of Education,9 laid down the foundations for ensuing research into the complex relationships and intersections between schoo...