eBook - ePub

Cereals in Breadmaking

A Molecular Colloidal Approach

- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cereals in Breadmaking

A Molecular Colloidal Approach

About this book

This reference text describes the breadmaking process at the molecular level, based on surface and colloidal science and introducing colloidal science with a minimum of theory.;Reviewing the current molecular and colloidal knowledge of the chain from wheat grain to bread, the book: discusses the structure of the dough, how a foam is formed during fermentation and how starch gelatinization induces the formation of an open-pore network, such as the bread crumb; covers new results on the gluten structure in bulk and at interfaces, as well as on phase separation in the dough; presents a complete model of all structural transitions from dough mixing to the formation of a bread; details the physicochemical properties of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates in wheat and other cereals, and considers their modes of interaction; and explores recent progress in the shape of biomolecular assemblies, derived from forces and curvature at interfaces.;The text provides nearly 850 citations from the reference literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cereals in Breadmaking by Ann-Charlotte Eliasson,Larsson Kare,Kare Larsson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Basic Concepts of Surface and Colloid Chemistry

I. INTRODUCTION

An ordinary light microscope can be used to study particles down to micrometer size. The world of colloids exists between this size and the size of individual molecules, down to about 10 Å. Consider one phase dispersed as particles in another phase, thus forming a continuous medium. With successively smaller and smaller particles within this size range, eventually a limit will be reached at which the two phases become one. An example of such a single phase is a micellar solution, which consists of amphiphilic molecules associated into an aggregate. It is a colloidal solution, and we call it an association colloid. The individual molecules, however, form a molecular solution. In this small size range of colloids we can also find various macromolecules, such as proteins, in solution.

If wheat flour is stirred in an excess of water, the proteins will cover the entire range of sizes of colloidal dispersions. Some of these proteins are insoluble in water but can still be dispersed. The dispersed particles, however, tend to collect into aggregates, and larger aggregates will form a sediment together with starch when the stirring ceases. The stable water solution will therefore contain only small particles—monomers of the water-soluble fraction of proteins. An important feature characterizing colloidal dispersions is the size of the interface between the particles and the continuous phase, the total surface area of the particles. The fat globule in milk, for example, exposes an interface between fat and water of almost 10 m2 per gram of milk. It is obvious that the nature of this interface plays a central role in our understanding of numerous properties of milk products, such as the separation of cream, the whipping of cream, and the formation of butter by phase inversion.

The importance of surface structure for colloidal phenomena is the reason for the close relation between surface science and colloidal science. This chapter presents the fundamental aspects, on the colloidal level, of the changes of the wheat endosperm from milling via dough mixing, fermentation, and heating to the final bread. Various crucial factors involved in baking properties—for example, the formation of gas cells and the gas-holding capacity of the dough—become obvious once we understand the underlying laws of surface and colloid science.

II. INTERFACES—SURFACE ENERGY AND SURFACE TENSION

Molecules in a liquid or in the bulk of a solid have neighbors in all three dimensions to interact with. In the surface layer, however, the molecules can interact only downwards toward the bulk or laterally within the surface plane. This is the reason for the existence of a surface free energy, which is the energy needed to increase the surface (or to bring molecules from the bulk to the surface layer). The surface free energy of a pure water surface toward air is about 73 mJ/m2, whereas it is much lower for nonpolar liquids such as triglyceride oil (about 30 mJ/m2). The surface energy is determined experimentally via the surface tension (γ), which is the force in millinewtons per unit length in meters that acts against increasing the area.

A drop hanging at the edge of a tube remains there because of surface tension (the mass of the drop is balanced by the surface tension), and this phenomenon provides one method to determine surface tension. Another method, described in the next section, is used to study the effect of surface-active molecules on the surface free energy. A third method is to use a capillary, provided that the walls are completely wetted by the liquid. The capillary force that causes the liquid to rise through the capillary tube is due to surface tension balancing the mass of liquid in the capillary above the level of the liquid outside the capillary.

III. SURFACE-ACTIVE MOLECULES-SELF-ASSEMBLY IN WATER AND MONOMOLECULAR SURFACE FILMS

In living tissues two groups of molecules tend to accumulate at interfaces: lipids and proteins. They are therefore classified as surface-active molecules, or amphiphiles. The driving force is their ability to reduce the surface energy between water and a gas phase or the interfacial energy between oil and water (or between solids and oil or water). Surface-active simple molecules such as lipids have one hydrophilic region; the rest of the molecule is hydrophobic. At an oil/water interface, the molecules of a monomolecular amphiphilic film will be oriented with their hydrophilic (water-attracting) region toward the water and their hydrophobic (water-repelling) region toward the oil.

Amphiphilic molecules form organized structures in bulk water by self-assembly. They do so because of hydrophobic effect, which is a tendency of the hydrocarbon region of the molecule to avoid water contact as it breaks the hydrogen bonds between water molecules. The structures obtained by such self-assembly of lipid molecules in water are further described below.

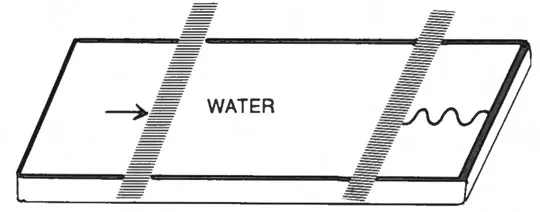

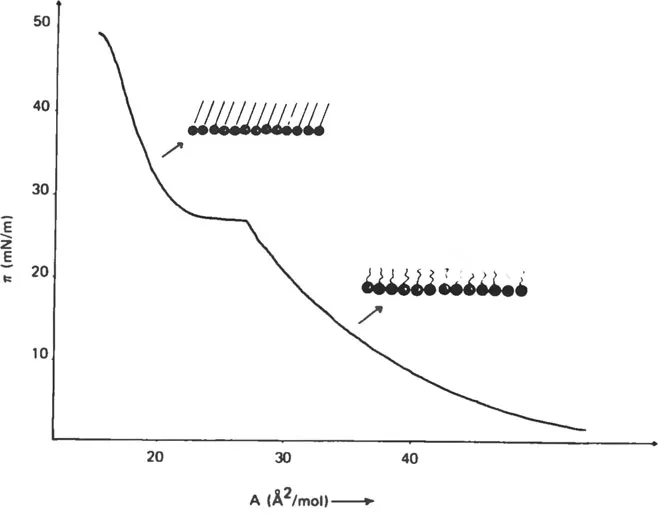

Suppose we have a pure water surface in a trough as shown in Fig. 1 with barriers defining the area. If a surface-active substance, for example, a long-chain fatty acid is spread from a solvent between the barriers, it is possible to record the pressure (π) versus molecular area of the fatty acid (A). The π-A isotherm is known from extensive studies of “insoluble” lipid monolayers to reflect the structure of the monomolecular film, as illustrated in Fig. 2. There are, in fact, the same structures as in the crystalline state of the lipid (solid state of the monolayer), in the lamellar liquid crystalline state (liquid condensed monolayer), or in the gaseous state. These corresponding lipid structures are described in later sections.

The surface film pressure π acts against the surface tension. Thus the surface film pressure is identical to the reduction in surface tension:

(1) |

Any protein in an aqueous solution will tend to go to the surface toward air, and the conformation and orientation it adopts will reduce the interfacial energy. A typical value of the reduction in interfacial tension when an excess of protein is present is about 20 mN/m. The absorption of proteins is usually irreversible, contrary to the behavior of lipids. This is due mainly to the size of the molecule. The protein molecule is often unfolded, and many water-insoluble segments of the peptide chain will be above the water surface. To undergo desorption, these segments would have to detach from the surface at the same time, which is very unlikely.

Fig. 1 Surface balance. One barrier can be moved to vary the area, whereas the other can record the presence of the surface film by the spreading pressure of the monolayer.

Fig. 2 Monolayer phases of a simple amphiphilic substance, one with lipid chains and the other (at high pressure) with crystalline chains. Polar heads of the molecules are indicated by circles, and the hydrocarbon chains by their axes.

Surface tension can be studied under various conditions using the surface balance, and even complex systems such as wheat lipids and wheat proteins can be successfully analyzed by spreading the corresponding monolayers, as will be described.

IV. INTERFACES OF SOLIDS—CRITICAL SURFACE TENSION OF WETTING

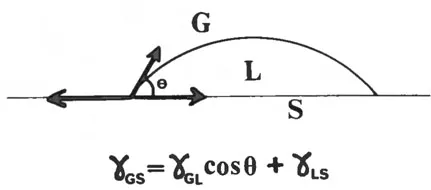

The surface energy of solids cannot be determined easily. A lot can be learned, however, from wetting properties. If a drop of liquid is put on the surface of a solid, it can either spread spontaneously, exhibiting complete wetting, or form a certain contact angle (θ) as shown in Fig. 3. The equilibrium conditions are given by the equation relating the interfacial tensions between the liquid and solid, between solid and gas, and between gas and liquid.

By studying the wetting properties using different polar/nonpolar liquids, it is possible to get indirect information on the surface properties of solids. A particularly useful concept is the critical surface tension of wetting, which is derived by plotting the cosine of the contact angle versus surface tension as shown in Fig. 4. The extrapolation to wetting gives the critical surface tension of wetting (γc).

Fig. 3 Interfacial tensions (γ) determining the contact angle (θ) of a droplet on a solid.

Solid surfaces can be classified as low-energy surfaces (e.g., polyethylene, which has a surface energy Π ≈ 30 mJ/m2) or high-energy surfaces. Pure metals have values of a few thousand millijoules per square meter in surface free energy, whereas the values for metal oxides are considerably lower. A liquid with a certain surface tension will always spread and wet a surface with a higher surface free energy.

V. THE ELECTRIC DOUBLE LAYER

When particles contain charged groups or have an adsorbed monolayer of an ionic surface-active substance that forms an interface toward water, there will also be an adsorbed layer of counterions close to the surface. The nature of this electric double layer is of utmost i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Basic Concepts of Surface and Colloid Chemistry

- 2 Physicochemical Behavior of the Components of Wheat Flour

- 3 Interactions Between Components

- 4 Components in Other Cereals

- 5 Flour

- 6 Dough

- 7 Bread

- Index