![]()

p.8

1 Love letters or hate mail

Translators’ technology acceptance in the light of their emotional narratives

Kaisa Koskinen and Minna Ruokonen

Introduction

In the past three decades, translation has rapidly shifted from a predominantly humanist profession to an increasingly technology-driven practice: translators have had to come to grips with such new technologies as word processing in the 1980s, translation memory (TM) tools in the 1990s, and, most recently, human-aided machine translation (MT), speech-recognition software and others. These technologies have repeatedly changed the face of the profession, challenging those working in this field to readjust their thinking and their work practices, and to constantly adopt new technology.

In the translation industry, new tools are introduced for rational reasons (speed, efficiency, accuracy), but the emotional side of new technology, and the effects of good or bad user experiences, are also relevant for explaining translators’ technology acceptance processes and for understanding the social effects of technologization on the translation profession. It has been observed that understanding and managing the emotions of different professional groups is relevant for those in charge of introducing new technologies in the workplace (e.g. Venkatesh and Bala 2008). It logically follows that, in introducing new translation technology, understanding translators’ emotions is highly relevant – in particular, given the general assumptions of translators’ technology-averseness and reluctance in accepting new tools (e.g., Drugan 2013: 24). Such assumptions, however, remain largely intuitive; the results that might be used to support or disprove this argument are either not very recent (see survey of literature in Dillon and Fraser 2006: 68) or are, by necessity, limited to a particular context (e.g. LeBlanc 2013). Interestingly, LeBlanc’s 50+ interviews at three Canadian translation agencies indicate that translators would not be opposed to new technologies (LeBlanc 2013: 10). Some evidence for or against technology may be explained by generational differences in attitudes, as found by Dillon and Fraser (2006: 73–5). There may also be differences in acceptance of information technology (IT) in general and translation-specific tools in particular (Fulford and Granell-Zahra 2005: 9–10). All in all, in translator–computer interaction (O’Brien 2012), translators’ emotions and affects are still a fairly under-researched area.1

This chapter looks at translators’ emotional narratives of the professional practice of translation, with particular emphasis on the role of technology in translators’ work. It reports the findings of an exploratory project in which participants were asked to write a short ‘love letter/break-up letter’ to the tool, application or aspect of work of their choice. This method comes from usability research, where it is used to study how people emotionally connect with devices and objects (Hanington and Martin 2012: 114), and it also proved useful for researching translators’ emotional attachments.

p.9

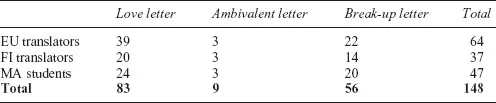

During spring 2014, a total of 148 letters were collected from 102 respondents (see ‘Research methodology and the respondents’). The data allows for a variety of analytical approaches. In this chapter, the focus is on attitudes towards technology. Of the 148 letters, 106 either focus primarily on technology or comment on it, and we use this subset as our data in the present study (see Table 1.2 for details).2

In the following sections, we discuss the relationship between technology acceptance and emotions, and explain the methodology applied in this research. We then present our findings. Following an overview of technology-related letters, we analyse the data from two more focused perspectives: we first look at the themes of time and change; we then map the letters against Jacob Nielsen’s (2012) widely applied usability matrix.

Emotions and technology acceptance

The starting point of this chapter is the well-known scientific fact that human cognition is closely intertwined with emotions, and thus our reactions and opinions towards any objects and matters in our lives are coloured by our emotions:

(Damasio 2004: 93)

More specifically, emotions also play a major role in acceptance of new technology. In various technology-acceptance models widely used in fields linked to IT and human-computer interaction (e.g., Zhang and Li 2005; Venkatesh and Bala 2008), attitudes and emotions towards technology have been identified as a central element of perceived ease of use, or the belief that using a particular system will be fairly effortless. This perceived ease of use, in turn, together with perceived usefulness, is fundamental to the user’s willingness to use a particular tool (Venkatesh and Bala 2008).

Technology-acceptance models have not yet, to our knowledge, been employed in translation studies, but effortlessness and usefulness are directly connected to usability research, which has recently gained more recognition within translation research (e.g. Byrne 2010; O’Brien et al. 2010; Suojanen et al. 2015). In a well-known usability definition created by Jakob Nielsen (2012), the main attributes of usability are listed as learnability, efficiency, memorability, errors and satisfaction. We will return to these attributes shortly. Here, we would like to emphasize that both efficiency and satisfaction are linked to ease of use and effortlessness: an efficient system increases the user’s productivity, because it is effortless and easy to use, and this is also likely to give rise to a sense of satisfaction.

p.10

Thus emotions, attitudes and (perceived) usability all interact and influence acceptance and adoption of new technology. Additionally, while emotions may appear ‘soft’, technology acceptance carries significant economic weight: low adoption and underutilization of IT systems have been identified as prominent factors in explaining why IT investments may fail to increase productivity (Venkatesh and Bala 2008: 274). It follows that insights into translators’ attitudes and emotions, together with perceived ease or unease of use – in other words, their user experiences – are also economically meaningful.

To summarize, translators’ attitudes towards technology and their experiences of its usability are likely to influence the degree to which they adopt new technology. It therefore seems necessary to chart the significance that translators attach to technology in general and to translation-specific technology in particular. In this chapter, we approach technology acceptance from two perspectives: first, that of translators’ attitudes; and second, that of the relationship between user experience and perceived usability, in which ease of use, as well as user satisfaction, play an important role. In the following section, we justify and describe the method we chose for this purpose.

Research methodology and the respondents

As pointed out, the method of writing a love letter/break-up letter to a tool or device has been used in usability research in cases in which the focus is on the emotions attached to devices and objects (Hanington and Martin 2012: 114). This qualitative, free-form method was deemed preferable to predefined technology-acceptance models for two reasons: first, because the method is designed to trigger emotional responses, it is ideal for teasing out emotions and attitudes towards various tools; and second, because the respondents were instructed to freely choose the subject of their letter, the data will allow us to see how extensively, if at all, translation-specific technology figures when compared to other aspects of work.

Because the purpose of the present study was to find out the relative status and role of technology in translators’ mappings of positive and negative emotions, the instructions for the task were given in a very broad manner, and the respondents were instructed to trust their first instincts and not to think too analytically before responding. The instructions also focused explicitly on experience and emotions, repeating words such as ‘pleasure’:

p.11

Table 1.1 All letters by respondents

Participation was entirely voluntary in each group and the respondents were free to write either a love letter or a break-up letter, or both. During spring 2014, a total of 148 letters were collected from 102 respondents (see Table 1.1), comprising:

• 44 professional translators in the European Union (EU) institutions;

• 26 professional translators working on the Finnish market;

• 21 Master’s-level translation students in Finland; and

• 11 Master’s-level translation students in Ireland.

Data collection raises some issues related to the selection of participants and to priming that may foreground technology. The EU data was collected in the context of a training session dealing with the future of translation technology; respondents were thus both, first, selected from among those interested in the topic and, second, primed to think about technological tools, perhaps to the detriment of other potentially more affective elements of their work. The Finnish data was collected through an online survey administered via social media, pooling respondents who follow digital media. Both sets of student data were collected during a visiting lecture: one on localization and usability (with potential selection towards technologically oriented students, but with the content more linked to user experience and emotions than to translation technology); the other on fieldwork methods (no obvious priming effects). (For a more detailed discussion, see Koskinen 2014.) However, to avoid pushing the respondents too heavily in one direction only, the respondents were explicitly encouraged to have a wide perspective on supports and hindrances:

Because each subgroup is rather small, quotations from the material will not be accompanied by any information about the respondents’ backgrounds, age or gender, because such information may inadvertently result in exposing the respondent’s identity. The respondents will be referred to by subgroup and code number only, for example ‘FI-61’.

p.12

As a method, the love letter/break-up letter invites respondents to produce narratives of emotion. It is important to stress that our data thus represents reported affect and discursively constructed tales of emotion; it does not allow direct access to the respondents’ psychological states. The data also contains retrospective material as opposed to data collected in the context of actual technology use (cf. Olohan 2011: 352–4). Collecting the latter kind of data would ideally require an observational fieldwork approach, since laboratory settings would not allow a realistic scenario. To our knowledge, such fieldwork data focusing on translators’ affective and emotional responses to technology use has not yet been collected; while LeBlanc’s interviews and observations may offer some pointers on these themes, his focus is broader (LeBlanc 2013: 1–2). Existing comparable research works with either survey data (Dillon and Fraser 2006: 68; Marshman and Bowker 2012) or Internet discussions (Olohan 2011) – that is, similarly reported and narrative-performative data.

On the other hand, retrospective and holistic research material such as these love and hate letters can be revealing in terms of long-term attitudinal factors as opposed to fleeting affects. The respondents were allowed to freely choose the object of their letter, as ...