![]()

CHAPTER 1

Production, Consumption,

and Demand

DAVID JAMES

1.1 INTRODUCTION

THIS chapter attempts to put into perspective the role of fish in the diet, its importance to poor people in developing countries, and the possibilities of maintaining or increasing supplies. It points out that, although accurate dried fish statistics are difficult to collect, dried fish production is decreasing, despite the growing nutritional demand. Although particular emphasis is put on the pattern of failure of attempts to introduce cheap industrial dried fish products for mass feeding, a continuation of such efforts is recommended.

1.2 PRODUCTION CONSUMPTION AND DEMAND TRENDS

Consumption of fish provides an important nutrient to a large number of people worldwide and thus makes a very significant contribution to nutrition. Except for the fatty species, fish is relatively unimportant as a source of calories, which are generally obtained from the cereal staples, but it is a palatable, convenient, and still moderately priced source of high-quality animal protein, vitamins, minerals, micronutrients, and essential fatty acids. The health benefits of fish are being increasingly recognized in Western society, which is an important factor in stimulating demand. In a large number of developing countries, fish has always been appreciated as a traditional and culturally acceptable component of the diet. Demand from this source is consistent and rising, giving great concern for future availability, in view of the limited nature of the resource. These concerns are expressed in more detail below.

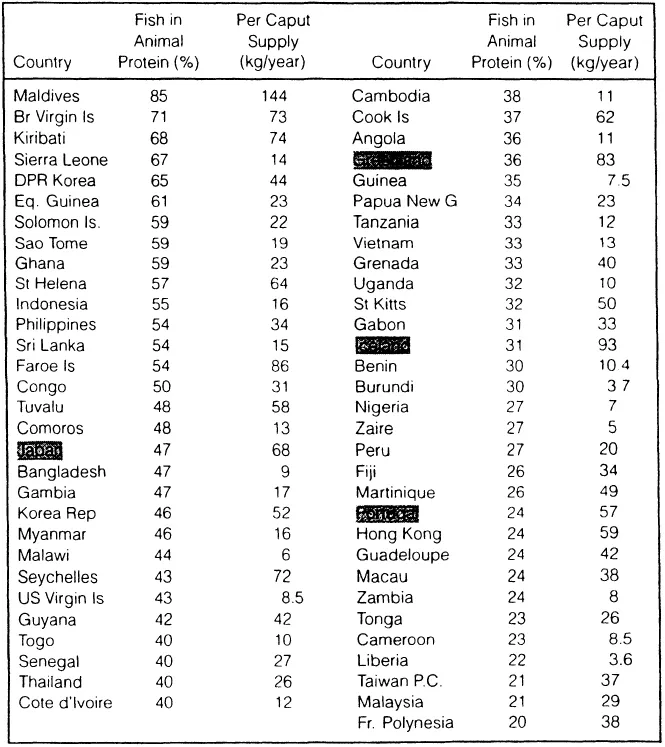

The total food supply available from fisheries (marine and inland) would give an apparent availability, as a live-weight equivalent, of about 13 kg/year for each of the world’s inhabitants. Availability and per caput consumption figures need to be viewed with some caution. What is normally quoted as per caput consumption is more often than not availability (production, minus exports, plus imports, divided by population) and not individual consumption, except in those countries where food consumption surveys have been carried out. Who actually eats fish or fish products within a population is heavily skewed to those who can afford them or alternatively to those who can find them in the market. Even at the first level of disaggregation, there is a discrepancy. Who actually consumes the 13 kg/head/year given above? Availability in developed countries is 27 kg per caput, while it is only 9 kg per caput in developing countries. Nevertheless, developing countries have a greater nutritional dependence on fish as can be seen from Table 1.1, which lists countries by the proportion of animal protein derived from fish. There are sixty-one countries that derive more than 20% of their animal protein supply from fish; only very few are developed countries. This is regardless of availability. There is also good evidence to suggest that the poor in these developing countries spend a greater proportion of their total animal protein expenditure on fish rather than on meat and eggs. Small island states have a particularly strong reliance on fish.

TABLE 1.1 Proportion of Fish in Total Animal Protein Supply for Human Nutrition.

Source FAO

The products of greatest relevance to the poor are dried fish products, usually produced by relatively simple traditional technologies. Throughout the world there is a very wide range of products, some of considerable regional importance in both developed and developing countries. The following products could be included in a list: dried; salted and dried; smoke dried (either salted or not); in brine or acid; fermented; and products resulting from a number of combination processes. In addition the product can be presented as whole fish, fillets, fish powder, or hydrolysates, such as fish sauce.

Traditional processing technologies have clearly been developed in order to preserve excess quantities of fresh fish for storage or transport. Usually these technologies are not well documented, particularly in developing countries, and are being lost with the trend to urbanization and convenience food. More effort is required to investigate and collect the processing methods. In the developing countries, products of this genre are usually made from low-cost raw materials, but in the developed world there is still a considerable demand for products such as dried, or salted and dried cod, where the raw material and the final product are of high value. The general importance of dried fish and the relatively simple technologies employed in its production have encouraged technologists to look for prospects of industrializing the process. The fact that these efforts, despite involving significant investment, have not succeeded is worthy of further investigation to see if they should be continued.

1.2.1 PRODUCTION

The quantity of fish that is converted to the various dried products is difficult to assess accurately. FAO statistics for 1993 imply the use of 3.2 million tons of raw material, approximately half coming from developing countries. Since 1977, production volume increased from 3.5 to almost 4.5 million tons in 1988, but showed a sudden drop to 3.2 million in 1992. In the same period developed country production reached a peak of 2.4 million tons in 1985, falling dramatically to 1.65 million in 1992 and 1993 when the Russian Federation produced half a million tons less than previously, mostly salted herring and mackerel. The main products in the European sector (North Sea and Atlantic) are salted and dried cod and the pelagic species, herring and mackerel. The salted and dried cod products have a traditionally strong market in southern Europe, West Africa, and Brazil as well as the Caribbean.

Raw material prices are putting the products beyond the purchasing power of many traditional consumers, and it is unlikely that production will expand. However, there is a prospect for increased substitution with cheaper hake products from Latin America. Retaining the traditional market of wealthier consumers will require development of better value-added products. Salted herring and mackerel also appeal to traditional markets in Europe and to a lesser extent North America, with some exports to Africa and the Caribbean, but earlier resource limitations tended to encourage production of higher valued products with the simple processing capacity being lost. As for the cods, there will probably be a continued core market for the traditional products.

Japan now accounts for slightly more than half the total developed country dried fish production. In contrast to the Atlantic, the main product in the north Pacific is salted and lightly dried salmon. Changing food habits tend to depress demand.

Developing countries’ production of dried fish, which reached a maximum of two million tons in 1988, also suffered a sharp reverse in 1992–93, falling to 1.55 million. West Africa is responsible for much of the shortfall, which could be associated with the withdrawal of the Russian fleet. West Africa has been an interesting case, demonstrating the value of the traditional technology. Fish caught by Eastern European vessels were held in frozen storage in the main centers in 20 kg blocks in cardboard cartons. They were transported toward the interior by small truck, bicycle, or head load. First sales were thawed frozen fish, the closest equivalent of fresh fish. Before spoilage the remainder was salted and lightly dried, being more heavily dried at a later stage if not sold. Developing country production is not characterized by a major product; rather, by the variety and size of the species used. Asia has a particularly rich variety of dried products, but many different species and product forms are also available in Africa. Burt (1988) gives a compendium of products. Africa still probably has the greatest nutritional reliance on dried fish, despite the worldwide tendency toward consumption in fresh or frozen forms. Reynolds (1993) points out that the lack of infrastructure is a serious impediment to shifting away from dried fish and that a lack of purchasing power restricts increasing consumption.

International trade in dried fish amounts to almost half a million tons, with more than 75% of exports coming from developed countries. It is almost certain that production, consumption, and trade, particularly in the developing world, are underestimated. Fish drying is often part of the informal economy, taking place outside existing trading arrangements. It is thus often unrecorded and does not enter into either consumption or trade statistics. In Africa, for instance, there is considerable border trade, which is undeclared to avoid duties.

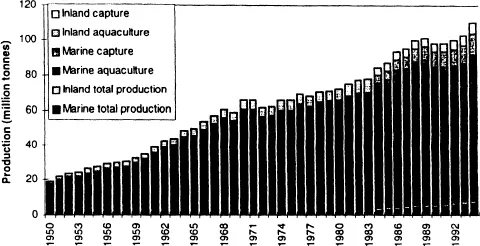

Figure 1.1 Evolution of fish production, including capture fisheries and aquaculture, from 1950 to 1993 (Source: FAO).

1.2.2 SUSTAINABILITY

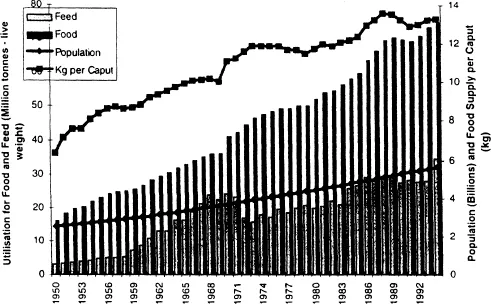

What are the prospects of sustaining the present levels of fish consumption? Figure 1.1 shows the evolution of fish production, including capture fisheries and aquaculture, from 1950 to 1993. By 1993 total production had risen to 101.3 million tons, but the pattern shows a declining rate of growth, with recent increases being attributed to aquaculture. The decrease in the rate is particularly apparent in the marine capture fisheries, which tends to support a growing body of evidence that the biological limits to marine production lie between 80 and 100 million tons, erring toward the lower figure. This is of great concern when one looks at the pattern of future demand, and even obtaining the supplies to maintain the present pattern of consumption looks very difficult. Projections of demand given in Agriculture Towards 2010 (FAO, 1993) indicate that to maintain present consumption levels of 13 kg/head/year for a forecast population of 7,032 million in 2010 would require 91 million tons of food fish compared with 72.3 million tons in 1993, an increase of almost 19 million tons. Figure 1.2 shows the impact of recent world population increases on availability.

Such an increase in food fish production is considered feasible if aquaculture production can be doubled in the next fifteen years and if significant improvements can be achieved in the conservation and management of capture fisheries through stock rebuilding and more rational harvesting practices. There would also be a need for better application of food technologies to improve the utilization of presently underutilized resources for direct human consumption, such as small pelagic species and the bycatches from trawling.

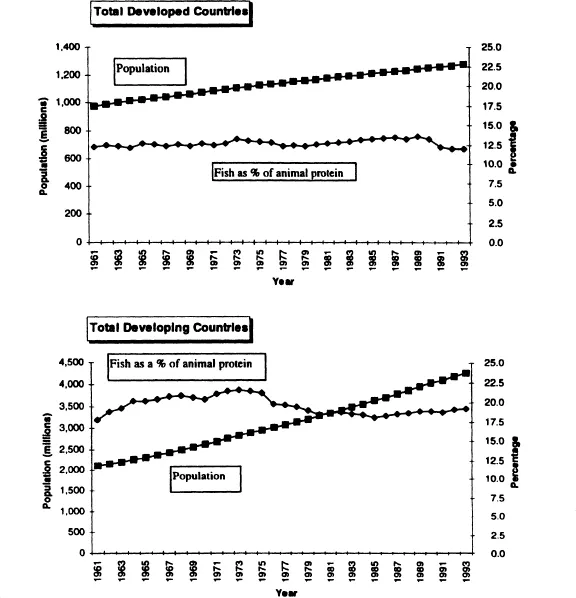

However, this projected increase of 19 million tons only takes into account additional demand as a result of population increase. It does not allow for an increase in incomes, which is an acknowledged part of the growth scenario, and would certainly result in an increase in fish purchases by present consumers. It also leaves out of consideration expansion of consumption to those who presently do not eat fish. The situation for the poor among the world’s potential fish consumers remains desperate. Even a small quantity of fish could make a significant nutritional contribution to the diets of this large and growing sector of the population. As a source of essential amino acids, essential fatty acids, minerals, and vitamins, the contribution is direct, but there are also side benefits from having a highly flavored component when the diet consists largely of bulky staples. Not only is the biological quality of the diet improved, but the addition of even a small quantity of fish, for instance in a sauce with a good flavor, increases the palatability thus increasing overall intake if supplies of the staple are sufficient. Figure 1.3 indicates the already declining trend in the proportion of animal protein derived from fish in developing countries.

Figure 1.2 World fish utilization and food-fish supply (Source: FAO).

Even despite the present strong demand, fish is still the cheapest form of animal protein, and although projected demand increases will inevitably cause fish prices to rise, fish will probably continue to hold this position, with dried fish, in one form or another, being the most economical fish product. In recent times the low price per unit of protein has led to many schemes to make fish available to the poor. Almost without exception these have all failed. Before considering the resources that might be available and the future prospects, it is instructive to consider the reasons for past failures.

Figure 1.3 World population growth and fish as a proportion of animal protein (Source: FAO).

1.2.3 A PATTERN OF FAILURE

The massive failure of the United States to develop and introduce fish protein concentrate (FPC) in the 1960s probably set the scene for subsequent failures of other, perhaps better conceived products. The story is poignantly told by Pariser et al. (1978) in Fish Protein Concentrate: Panacea for Protein Malnutrition? Briefly, in the heady years of the Kennedy administration, a technological fix of using the apparently limitless resources of the sea to feed the poor and to benefit American industry seemed to be a brilliant idea. Ten years later, in 1972, after a long, expensive, and sometimes acrimonious struggle, the project was abandoned as a failure. The principal cause was the intransigence of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which blocked introduction of a product made from whole fish as containing “filth.” Other barriers were raised, such as its ruling that the product should be considered as a food additive rather than a food, and that the fluorine content should be limited. The political will to overcome these constraints was not apparent, and there were additional technological limitations in production and incorporation into the diet. In keeping with the thinking of the time that protein deficiency was the scourge, FPC was conceived as a bland protein supplement extracted from fish that could be added to any diet. The solvent extraction process was difficult to control and costs of solvent recovery high. In addition the product suffered from flavor reversion in storage, with fishy flavors reoccurring. No substantial production resulted in the United States, and very little testing was done in the developing world. The choice of an extracted FPC with a very low lipid content (subsequently called FPC Type A) was probably the result of the United States industry’s vested interests and must be seen to have contributed to the debacle and to have influenced other later and perhaps more promising initiatives. The best summing up was perhaps by Professor Harold Olcott, who commented that FPC was “colorless, odorless, flavorless and useless.” People did not want to eat mysterious white powders labeled nutrition but preferred fish recognizable as a familiar food item. The Astra Corporation in Sweden became the only significant producer, offering the product to government and international famine relief programs during the late 1960s and early 1970s before ceasing production due to lack of demand.

The next stage of development was with FPC Type B, a product made from fatty fish with a residual fat content of up to 8%. Based on earlier attempts in South Africa, Iceland, and elsewhere, the Norwegian company, Norsildmel, started product development and marketing in the 1970s, and Norway funded a substantial program of acceptability and market testing through FAO. While some success was achieved, the causes for rejection, reported in documents from the project (FAO, 1976, 1978), were primarily:

• the identification of the product with the poor and starving reduced its marketability

• the insistence of the producers in using a sanitized version of fishmeal technology resulted in a product with a gritty mouthfeel and poor suspendibility

More recently Norsildmel has developed a fish flour, Product 305 (British Patent, 1978), which is produced commercially and used as the main ingredient in instant soups, sauces, and similar products. Very little has appeared in the scientific and technological literature regarding the processes used for this purpose. The Alpha-Laval company has developed a process and is providing equipment to factories in Europe and Alaska for producing edible fish flour made from white fish filleting waste.

Food aid agencies have shown increasing reluctance in using the product due to its high cost per unit of protein compared to the staples, difficulties in storage, and the absence of a high level of acceptability except in certain situations. Experience showed that it was useless to try to introduce FPC Type B to non-fish-eaters and as part of emergency relief activities. Where consumers were familiar with the flavor of fish and did not reject rancidity, the product was acceptable and even commercial development was possible, such as in Southeast Asia and the Caribbean (FAO 1980). Up to this stage of the development, the search for a cheap powdered fish product for the poor consumer had been driven by technology rather than ...