- 648 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Enzymology for the Food Sciences

About this book

This second edition explains the fundamentals of enzymology and describes the role of enzymes in food, agricultural and health sciences. Among other topics, it provides new methods for protein determination and purification; examines the novel concept of hysteresis; and furnishes new information on proteases, oxidases, polyphenol oxidases, lipoxygenases and the enzymology of biotechnology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Principles of Enzymology for the Food Sciences by John R. Whitaker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

I. Breadth of Enzymology

The area of enzymology is of special interest to both the biological and physical sciences. Enzymes are of universal occurrence in biological materials, and life itself depends on a complex network of chemical reactions brought about by specific enzymes. Any alteration in the normal enzyme pattern of an organism may have far-reaching consequences. Enzymes, as catalysts, are of great interest to the physical chemist, and investigation of the mechanisms of action of enzymes is a very important area of enzymology.

The area of enzymology has continued to grow rapidly for more than 60 years because of its importance to a large number of the sciences, especially biochemistry, physical chemistry, microbiology, genetics, botany, zoology, food science, nutrition, pharmacology, toxicology, pathology, physiology, medicine, and chemical engineering. Enzymology has important practical applications to activities as diverse as brewing and industrial fermentations, pest control and chemical warfare, dry cleaning, sizing and detergents, analytical determinations, and recombinant DNA technology.

Many research workers in universities, research institutes, and private industry around the world are devoting their attention to both the basic and applied aspects of enzymology. Symposia and general paper presentations on enzymes are substantial parts of all national and international professional meetings in biology and chemistry. Several journals, monographs, and textbooks devoted in part or completely to the subject exist and the literature in the field of enzymology is immense. While no one can know more than a fraction of the total definitive and descriptive information on enzymes, all must build their work on certain common, basic facts and principles concerning enzymes.

II. Brief History of Enzymology

A. Discovery of Enzymes

The major growth in enzymology has occurred relatively recently. Beginnings of enzymology can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, but the great developments have come during the last 60 years. Although the phenomena of fermentation and digestion were known before, the first clear recognition of enzyme involvement was by Payen and Persoz in 1833 [1], when they found that an alcohol precipitate of malt extract contained a thermolabile substance that converted starch into sugar. This substance, now called amylase, was named diastase by Payen and Persoz because of its ability to separate soluble dextrins from the insoluble envelopes of starch grains.

Enzymes such as catalase, pepsin, polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase, and invertase were known by the middle of the nineteenth century. In 1855, Schoenbein described an enzyme (peroxidase) in plants which, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, caused a solution of gum guaiac to turn from brown to blue [2], In 1856, Schoenbein described the presence of another enzyme (polyphenol oxidase) in mushrooms which, in the presence of molecular oxygen, brought about the aerobic oxidation of certain compounds [3]. In 1860, Berthelot [4] discovered an enzyme in yeast which was subsequently named invertase because of its ability to change the direction of optical rotation of a sucrose solution (by hydrolysis to glucose and fructose). Several other enzymes were discovered during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

B. Nature of Enzymes

Earlier researchers had observed a parallelism between the action of enzymes and that produced by yeast during fermentation. The name ferment was consequently used for enzymes. During this time, the opposing views of Justus Liebig, who held that fermentations and similar processes were due to the action of chemical substances, and those of Louis Pasteur [5], who maintained that fermentation was inseparable from living cells, caused considerable controversy. The names unorganized ferments and organized ferments were used to denote what would now be called extracted enzymes and microorganisms, respectively. It is easy to see how this division could come about since there were enzymes from malt (amylase) and from the stomach (pepsin) which were active in the absence of living organisms. On the other hand, fermentation was thought to take place only in the presence of living organisms but not in their absence.

C Origin of Name Enzyme

In 1878, Kühne [6] proposed use of the word enzyme (Greek, “in yeast“) to avoid the use of the names unorganized and organized ferments. Kühne’s reason for suggesting the use of the term enzyme is best explained in his own words [translated in Ref. 7, p. 204, by courtesy of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]:

The latter designations (formed and unformed ferments) have not gained general acceptance, since on the one hand it was objected that chemical bodies, like pepsin, etc., could not be called ferments since the name was already given to yeast cells and other organisms; while on the other hand, it was said that yeast cells could not be called ferments, because then all organisms, including man, would have to be so designated. Without stopping to enquire further why the name has excited so much opposition, I have taken the opportunity to suggest a new one, and I give the name enzymes to some of the better known substances, called by many unformed ferments. This name is not intended to imply any particular hypothesis, it merely states that en zyme (Greek, in yeast) something occurs which exerts this or that activity, which is supposed to belong to the class fermentative. The name is not, however, intended to be limited to invertin of yeast, but it is intended to imply that more complex organisms, from which the enzymes pepsin, trypsin etc. can be obtained, are not so fundamentally different from the unicellular organisms as some people would have us believe.

The Liebig–Pasteur controversy came to an end when Büchner, in 1897, succeeded in obtaining the fermentation system from yeast in a cell-free extract [8].

D. Enzyme Specificity

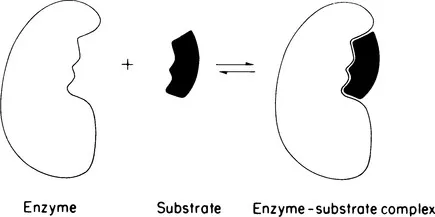

The great German chemist Emil Fischer developed the concept of enzyme specificity and of the close steric relationship between an enzyme and its substrate. On the basis of careful studies with synthetic substrates, Fischer enunciated his famous lock-and-key analogy of enzyme-substrate interaction in 1894 [9], This relationship is shown schematically in Fig. 1. Fischer’s concept of the necessary close stereospecific fit between enzyme and substrate has influenced thinking on the nature of the enzyme-substrate complex to the present day. A necessary consequence of the close fit between enzyme and substrate is that each enzyme acts on a limited number of compounds. Proper studies of enzyme specificity require highly purified enzymes and substrates of known structure and purity. Based on the specificity concepts of Fischer, Bergmann and his students synthesized many peptides during the 1930s and 1940s for study of the action of proteolytic enzymes. They showed that a proteolytic enzyme hydrolyzes a given peptide bond only if the specificity of the enzyme is satisfied by the amino acid residues in proximity to the susceptible bond of the substrate. Furthermore, they were able to divide the proteolytic enzymes into endopeptidases and exopeptidases, depending on the enzymes’ preference for hydrolyzing peptide bonds in the interior or at the terminal end of a peptide.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the lock-and-key analogy of enzyme-substrate interaction.

Another important contribution to the concept of enzyme specificity was Koshland’s induced fit concept of enzyme–substrate combination in 1959 [10], While Koshland’s induced fit theory retained the concept of a stereospecific complex formation between enzyme and substrate, it rejected the idea that the binding locus of the active site is a rigid structure that maintains a configuration complementary to the substrate even in the absence of substrate. Rather, the presence of substrate near the active site could cause some changes in the active site so as to bring about a closer fit between substrate and enzyme and to bring the groups involved in the conversion of substrate to product into proper juxtaposition. The extent of flexibility of the active site probably varies markedly among different enzymes.

E. Quantitation of Rates and Reactions

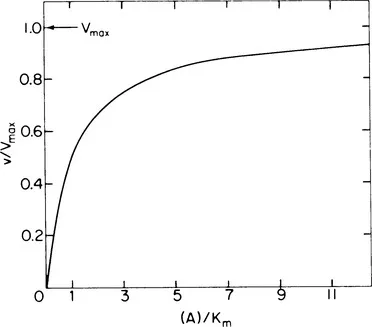

The first part of the twentieth century saw the development of quantitative methods for describing the action of enzymes. In 1902, Henri [11] and Brown [12], independently, suggested that the saturation-type curve obtained when increasing amounts of substrate are added to a fixed amount of enzyme (Fig. 2) is the result of an obligate intermediate, the enzyme-substrate complex. In 1913, Michaelis and Menten [13] derived their now famous mathematical expression which describes quantitatively the saturation-like behavior:

where v is the observed velocity, Vmax the maximum velocity when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, (A) the substrate concentration, and Km the substrate concentration at which v = 0.5Vmax. In 1909, Sorenson developed his classic paper on the effect of pH on enzyme activity.

Figure 2 Relationship between substrate concentration, (A), and observed velocity, v, for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction. When (A) = Km, v = 0.5Vmax. Notice that even when (A) = 12Km, v is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Protein Nature of Enzymes

- 3 Enzyme Purification

- 4 Active Sites and Factors Responsible for Enzyme Catalysis

- 5 Rates of Reactions

- 6 Effect of Substrate Concentration on Rates of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

- 7 Effect of Enzyme Concentration on Rates of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

- 8 Kinetic Consequences of Enzyme Inhibition

- 9 Enzyme Inhibitors

- 10 Effect of pH on Rates of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

- 11 Effect of Temperature on Rates of Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

- 12 Enzyme Cofactors

- 13 Classification and Nomenclature of Enzymes

- 14 Introduction to the Hydrolases

- 15 The Glycoside Hydrolases

- 16 Pectic Enzymes

- 17 The Esterases

- 18 The Nucleases and Biotechnology

- 19 The Proteolytic Enzymes

- 20 Ordinary and Limited Proteolysis

- 21 Introduction to the Oxidoreductases

- 22 Lactate Dehydrogenase

- 23 Glucose Oxidase

- 24 Polyphenol Oxidase

- 25 Xanthine Oxidase

- 26 Catalase and Peroxidase

- 27 Lipoxygenase (Lipoxidase)

- Index