![]()

1

A PROMISCUOUS EYE: ON RACE AND THE FLOWER

Robert ritualized black men for sex. He was like Holden Caulfield who thought he was not a man until he had made it with a black woman. In a sense, because the black photographs buzz a running subtext to the leather photographs, white-southern senator Jesse Helms may have had no more quarrel than a bad case of sex-race penis envy … Mapplethorpe’s black photographs are chic advertisements of miscegenation. He dramatized black men as desirable sex partners to a nation that for three centuries had lived in sexual fear of black men.1

JACK FRITSCHER

Black Men with Flowers

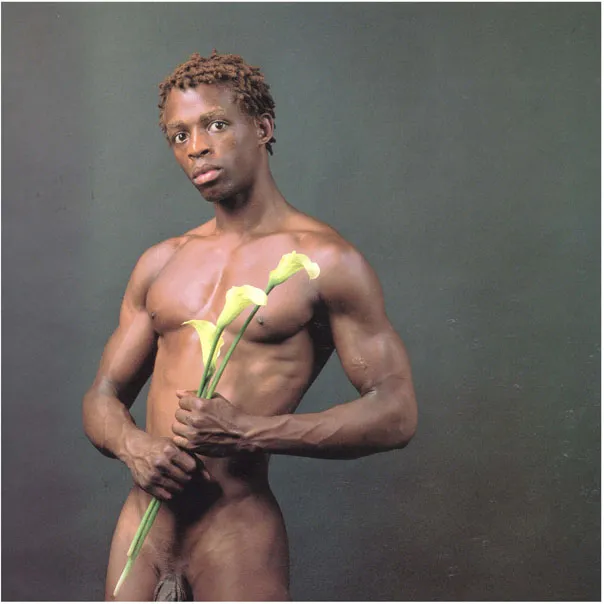

My interest in the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe began roughly ten years ago, when I encountered a reproduction of a work entitled Dennis Speight with Calla Lilies (1983), a striking color photograph of a roughly twenty-something black man, looking almost quizzically into the camera, while holding two long-stemmed flowers. Up until that point, I had primarily associated Mapplethorpe with formalist photographs of celebrities, still lifes, and classical nudes. I was aware of his more notorious sex pictures and leathersex images, particularly as they pertained to governmental efforts to censor the artist’s work. But it wasn’t until I chanced upon Dennis Speight that I began to take notice. The Speight image has a certain drama about it that brings together several interlocking themes that run through the majority of the photographer’s vast body of work. In the quotation above, Mapplethorpe’s former partner and author Jack Fritscher writes very candidly about the photographer’s fascination with black men, both sexually and representationally—though Fritscher does not dance around what he characterizes as the artist’s casual racism. Mapplethorpe’s interest in black men seemed to vacillate between racial fetishism and kinship, a fact that has been written about endlessly in biographies and gossipy accounts of the artist’s colorful life in New York during the 1970s and 1980s. The Speight image is fascinating precisely because of the interplay between the flower and the figure: the delicateness and eloquence of the calla lilies, set against the physical strength and beauty of the sitter. Arguably, the most powerful characteristic of the photograph is the returned gaze, the piercing look that Speight directs back at the photographer. His gaze has a clear defiance, although it is neither aggressive nor confronting: rather, it is knowing and claims a certain agency that would contradict a purely fetishistic reading of the image. How we interpret the photograph has been impacted by a range of issues that are, in fact, distinct from the image itself, though not totally adrift from it.

Figure 1 Robert Mapplethorpe, Dennis Speight with Calla Lilies (1983). © The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

Speight’s blackness—the dark browns and sienna tones of his skin—reveal subtle nuances that grate against the racial reductions that subtend the manner in which the black male body is visually read. He is a vision of physical beauty: lithe and lean, muscular, but also slight. Unlike many of his images of nude black men, the Speight portrait is cropped to reveal just the slightest hint of his shaved genitalia. It is an image that exudes the restraint and control of intention—but not a desire to shock or offend. On the contrary, it is devotional in its softening of a physical subject so overdetermined by pathology and social dysfunction, and it more rightly functions as a corrective—forcing his viewers to find the beauty in a subject that has not been culturally codified in such a manner.

Mapplethorpe’s photographs of black men with flowers allude to French writer Charles Baudelaire’s volume of poetry entitled Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil). First published in 1857, Baudelaire’s metaphorical vision of the floral engages with themes of eroticism, decadence, lust, and desire; he finds a subversive monstrousness in ideal beauty, and an alluring splendor in the grotesque. We see this symbolism throughout the histories of art, from the masters of seventeenth-century Europe through to our contemporary moment, as reflected in the work of pop artist Andy Warhol, Mapplethorpe, as well as his Afro-British contemporary, artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955–89). Fani-Kayode—who, like Mapplethorpe, succumbed to AIDS in the late 1980s—was known for his complex symbolism, which often took the form of richly colorful photographs of black men with flowers.2

One of the striking aspects of Mapplethorpe’s Speight photograph is its function as a precursor to current movements in photography. In the twenty-first century, the thematic conjunction of black men and the floral has reemerged. For example, Los Angeles-based photographer Brandon Stanciell (b. 1994), aka “the Man Who Loved Flowers,” has built a significant reputation for his portraits of young black men, presented in highly staged photographs where his subjects are elaborately adorned with flowers. Stanciell’s portraits have a specific political intent, which is to reimagine black masculinity beyond the rhetoric of pathology, violence, and the hyper-masculine hardness usually associated with black men in the American cultural imagination:

There is a huge misconception of black men in media all around us. We’re portrayed sometimes as “Aggressive” and “Thug” and that’s not always the case in many black communities. My concept for “The Boys Who Loved Flowers” is to portray a more sensitive side of black men. A side most people are not familiar with. The flowers help communicate a more calm setting and their bright colors bring the viewer’s attention to the subject. Allowing the viewer to feel things like sensitivity and peacefulness. Words not commonly associated with black men.3

Stanciell’s frankness around his corrective vision gives a kind of retroactive insight into the potential motivations behind Mapplethorpe’s Dennis Speight with Calla Lilies, in that it frames the representational motivations as residing in a need to reposition the black male beyond threat and menace. While none of his subjects are nude, Stanciell’s portraits present young black men as sensitive bohemians, with a certain carefree demeanor more associated with privilege than persistent struggle. One of his photographs, Thinker of Overgrown Thoughts (2015), is a rather traditional-looking portrait of a young black man whose body is in profile, but his head is turned towards the viewer, as he stares directly into the camera. His expression is almost stern, but not angry. However, the forcefulness of his gaze is offset by the copious amount of red and white flowers decorating his ample afro. Draped around his shoulders and neck is a type of makeshift wreath of green leafed vines. It’s a contradictory image that conveys both vulnerability and strength, yet it is most importantly devoid of sexual desire. The queer desiring gaze that Mapplethorpe conveys with such unabashed forcefulness is absent in Stanciell’s image—though the queering is still present. In the younger artist’s image is what has been characterized as the “carefree black boy,” a term that has become popular among millennial image-makers.4 It describes a vision of black masculinity that is alternative and quirky, if not a bit unexpected, but it simultaneously queers black male representation—liberating it from the stifling logics of tragic heteronormativity. Stanciell’s bohemian black boy exudes a type of artsy nerdiness with his Malcolm X-like glasses and afro, both signifiers of militancy and resistance with historical undertones—yet these references are complicated by the sitter’s nose ring, which brings an alternative edge to the image.

In contrast, Mapplethorpe’s Dennis Speight is a more labored-over and formally exquisite photograph, with its meticulously staged studio lighting and dark gray background, which perfectly contrasts the sitter’s skin tones. Speight’s pose is almost awkward in the way his body simultaneously twists, yet leans backward, while his head tilts downward and to the side, ever so slightly. The pose is intentionally stilted, which renders it more sculptural than naturalistic. The image recalls Mapplethorpe’s 1988 work entitled Spartacus, a beautifully rende...