![]()

1

Drawing on the past

A historical context for graphic investigations

This chapter provides a historical context for an argument about drawing’s value as an investigative tool and its contribution to knowledge outside the arts in the past. It acknowledges the significance of the collapse of modernism and emergent postmodernism in the mid- to late twentieth century for establishing fruitful environments for cross-disciplinary dialogue which have in turn re-established connections between drawing and other spheres of social, political and academic activity.

Context is important because the history of drawing is not the same as the history of art. To consider drawing made only in the services of art making would be to overlook the vast proportion of drawings which have ever been made, including a swathes of graphic material that have come to inform contemporary uses of drawing. For instance, the legacy of sea charts, architectural plans, fashion design, medical and botanical illustration can be seen in certain approaches to drawing today. Indeed, a study of drawing’s provenance outside the arts could be an engaging book in itself, so intertwined is drawing in the daily practice of life.1 It is arguably because of this entangled past that drawing now readily adapts to collaboration and application outside the arts. Without entering discussion of design drawing, which as we have already explained falls outside our remit, this chapter offers insight into the breadth of drawing’s historical use as a tool of exploration in and beyond art, providing context for discussion of contemporary practice. While a comprehensive survey of vernacular graphic history is beyond the scope of this book, what follows attempts to highlight indicative practices, uses, methods and ideas that have relevance for investigative drawing today.

Early investigations

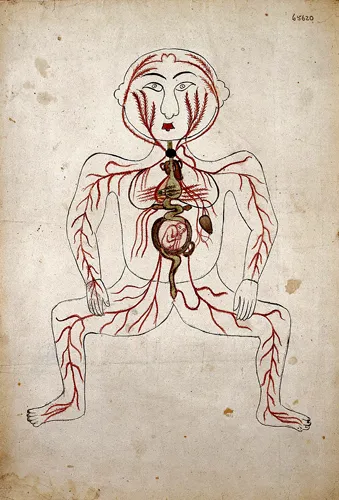

Drawing has a long and varied history as a tool of investigation outside the arts across Eastern and Western cultures. Our earliest known records of comets are documented through linear ink drawings on silk made in China in the second century BC.2 Among the earliest botanical manuscripts are those containing exquisite naturalistic drawings produced by Ibn Sarabi, an Arab physician around AD 800.3 In the fourteenth century, Persian anatomist Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Yusuf ibn Ilyas illustrated the five bodily systems described in his treatise Anatomy of the Human Body (Figure 1.1).4 These diagrams systematically laid out a clear visual explanation of the invisible interior workings of the human body.

FIGURE 1.1 Unknown Persian artist. Body with a foetus in the womb. Watercolour with pen and ink. 31.3 × 21.7 cm. Pasted into Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Yusuf ibn Ilyas, Mansur’s Anatomy (c.1390). Wellcome Collection – Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0).

Within the western European tradition, drawing has been allied since the Renaissance with knowledge production in a way that distinguished it from painting or sculpture. Drawing, as disegno, became equated with ideas and was regarded as a marker of an artist’s intellect and strength.5 In The Craftsman’s Handbook of 1437, Cennino Cennini (1360–c. 1427) argues that the act of image making is a skill and virtue second only to theory, attempting to position himself, an artist, among an intellectual elite as opposed to artisan producer.6 The distinction that Cennini makes is important because it highlights the break between a medieval concept of art and artists and the emergence of a modern one based on empirical study of the world which demanded new means of training artists.

In medieval Europe, the main demand for artwork was religious. Artists were craftspeople who worked within workshops from pre-existing imagery. It became common practice for workshops to have model books, known as exempla – visual compendiums of imagery – from which the artist could copy and learn. These reference books might be seen as the first ‘sketchbooks’, although a crucial distinction is that they were not regarded as artworks and functioned as a tool to supply ‘specific types of imagery for use in the workshop’.7

From around 1400, in both northern and southern European traditions, new ways of depicting and representing the world came to the fore. Art became illusory, or rather had new standards of illusion as visually mimetic semblance of the world replaced earlier symbolic and metaphysical conventions.8 This was both influenced and supported by developments in mathematics. Procedures of mapping and measurement were adapted to drawing.9 Methods such as linear perspective assisted artists in creating a convincing representations three-dimensional space on the flat plane of the page.10

Where artists had previously been copyists repeating models of universal types, their training now had to be grounded in studying the visual world. This is a crucial shift underpinning the development of the investigative drawing practices we are interested in. Antonio Pisano (1395–1455), known as Pisanello, is an example of an artist moving through this transition period from craftsman to artisan and respected artist in the employ of the Gonzaga family. His sketchbooks do not follow previous models, made in the workshop solely for workshop use. They are clearly made by an author and his drawings are original images, often made while travelling for purpose of gathering information. They are filled with observations including travel notes, fragments of figures, studies of animals and scenes of the everyday. His acute interest in the details of his contemporary world is unmatched until Leonardo’s studies for his treatises. They comprise the largest number of drawings left by any fifteenth-century artist.11

Pisanello’s example marks the shift from the medieval model book towards a sketchbook as defined in modern terms. It also reflects the shifting importance of travel and experience outside the hermetic environment of the workshop. While artist-craftspeople had necessarily moved cities to take up employment, encounters witnessed on their travels were now recorded on site, either for the artist’s own record of images or at the behest of a patron.12 The genesis of the sketchbook as a tool for gathering imagery and recording observations of the world is integral to the type of drawing featured in this book. The modern sketchbook was borne out of a paradigmatic shift towards artists studying the visual world. The emergence of this technology has supported the practice of investigative drawing ever since.

The use of model books persisted in workshops as a guide for artists. They played a role in training the eye to see shape and form, which could be adapted to accommodate details of the particular.13 Studio workshops were also filled with props and importance was placed on observational drawing from life. There are a number of accounts of Renaissance painters having studied natural specimens so attentively that modern botanists are now able to identify the species of plant depicted from the paintings, for instance in Botticelli’s Primavera (c. 1492).14 Leonardo’s plant studies for Leda and the Swan appear to have become a study in their own right. They are now regarded as important as botanical records, being more accurate than herbals of the time.15

This shift meant artists were now trained to be skilled observers. Aligned with the emerging concept of ‘science’, drawing became the tool for thinking and discovery, an aid to knowledge production and documentation and an instrument of imagination, of visual thinking. Examples of this might be drawings by Andreas Vesalius (1514–64) to record his dissections or studies by Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) of the surface of the moon. Equated with ideas, drawing was reframed as an intellectual activity, as opposed to the tool of the manual craftsperson.16 In fact, the distinction we see now between artistic and scientific knowledge was not then so. Research has shown how Galileo worked closely with artists and that his astronomical work reflects the influence of artist contemporaries.17 As Joseph Amato poetically expresses it, ‘The best artists were the observers and engineers of the age. They were light’s most faithful servants, piercing the darkness, removing the dust, and grasping essential but intangible forms.’18 In a period and culture supportive of empirical investigation into the workings of the body, world and heavens, drawing provided the necessary visual technology for documentation, speculation and the synthesis of the two. Its capacity to render insights in clear, linear, visual form was a valuable means to communicate discoveries to others.19

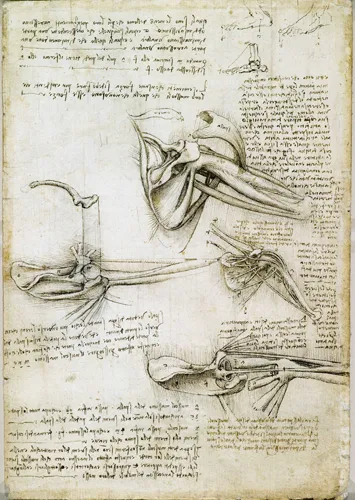

The most oft cited Renaissance exemplar of investigative drawing is Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Although it is inaccurate to present Leonardo as typical, he was influential, as Claire Farago and others have shown.20 Moreover, his legacy of notebooks and drawing is particularly useful to us. Leonardo’s reflection on the purpose of drawings in his notebooks offers useful insight into his wor king processes and the value he placed on drawing. Take, for instance, his anatomical studies (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Leonardo da Vinci. Anatomical drawing. Recto: The bones and muscles of the shoulder (1510–11). Pen and ink with wash over black chalk on paper. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

In his notebook, Leonardo also tells us that it was ‘necessary to precede with several bodies by degrees’, so the drawings are the result of studying multiple dissections of multiple bodies over a period of time.21 This is evident to a viewer examining notebook studies in which we ca...