![]()

Some stages of learning to read and write take longer, require more practice and demand better instruction than others. For example, learning whether text in your language goes from left to right or right to left is fairly easy, and once learned, is seldom forgotten.

Learning to convert the symbols on the page to speech is another matter. Language is a reflection of the workings of the mind and is therefore necessarily complex, even at the oral level. Adding writing to the picture puts an additional code-making/code-breaking component into an already complex structure.

Human writing systems have only been around for 3,000 years or so, and though they convey oral language, they did not develop in the same way as oral language. It’s a good idea to remember this when thinking about how children are taught to read. Here are some basic principles that can help.

• Reading and writing is not the same as listening and speaking. Therefore, we get better results when we remove the expectation that children will just start reading in the same way as they just started speaking.

• Learning to read is not the same as skilled reading. Therefore, we get better results when we are aware of the process of learning to read and when we teach towards that. Skilled reading is a destination; the journey is somewhat different.

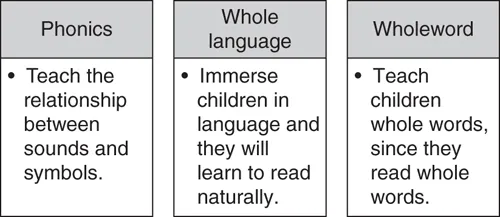

Falsehoods flourish in the presence of complexity, and, even to this day, there are people who not only believe, but viciously defend outdated, demonstrably incorrect views of reading. The two major false ideas can be classified as whole language and whole word approaches to teaching reading.

When poor reasoning occurs, the vulnerable inevitably suffer. In many cases, a lack of understanding of the building blocks of literacy leads to poor teaching and ineffective intervention (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The three major theories of reading

The Simple View and dual coding

To begin with, any theory of reading instruction must have a perspective on what reading actually is.

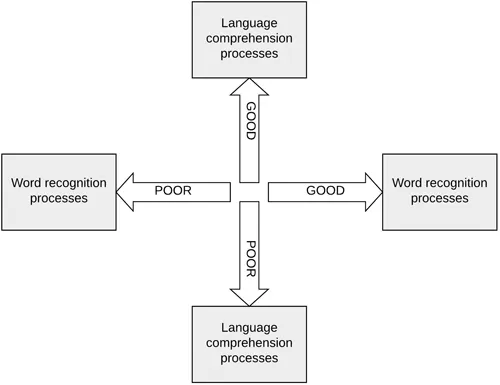

Reading experts often refer to the Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer 1986). This is a formula designed to help educators assess and assist readers.

The Simple View states that skill level in reading comprehension can be predicted by measuring two processes:

1. word recognition

2. language comprehension

So, the better you can convert the letters on the page into sounds and words, and the more words you understand, the more you’ll be able to comprehend what you’re reading (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Simple View of Reading

The Simple View of Reading is a logical, testable formula grounded in decades of research.

Along with this, and slightly more technical, the Dual-Route Approach is a model of reading aloud which suggests that two separate cognitive pathways are involved in and available for the pronunciation of a written word (Coltheart 2007). Those pathways are the phonological and the semantic. The phonological route assists in reading all words, whilst the semantic route can only assist in reading regular or known real words.

Dual Route Theory is fascinating, but too complex for this book. Further reading is highly recommended, however. I mention it because it explains the confusion that educators sometimes experience when comparing the journey to the destination in reading.

The Big Six

Word-level recognition relies on six key skills. First referred to as The Big Five (Chall 1983), and later on – with the addition of oral language development – as the Big Six (Konza 2014), they are:

1. oral language development

2. phonological (including phonemic) awareness

3. phonics

4. fluency

5. vocabulary

6. comprehension

This section defines each skill. Later on, Section 4 builds on this information to provide a helpful guide to assessing and teaching these and related skills.

Many in opposition to, or who do not fully understand, the science of reading will lump all of the above under the umbrella of ‘phonics’. A better description would perhaps be ‘structured literacy’.

Whole language: A linguistic profile

There are other perspectives which fail to link decoding to comprehension, or which place undue emphasis on comprehension and dismiss decoding altogether.

Back in the 1960s, there was a movement in educational circles which claimed that a code-based, systematic approach to teaching reading was wrong. This general kind of challenge to convention, conformity and authority was popular and led to many great changes in civil rights, etc. In education, however, it led to the disastrous rise of whole language.

It is not easy to pin whole language down to one single definition. Whole language is more of a force, a set of ideas and a suite of related methodologies. It is based on two flawed principles:

1. That children learn to read in much the same way that they learn to talk (they don’t), because learning to read is a natural process (it’s not).

2. That immersing children in a literacy-rich environment will lead them to discover the structure of the written code by themselves (it won’t).

There are few people who describe themselves as whole language practitioners or who say their methods are whole language based, but there are certain words and characteristics associated with the movement.

Firstly, anyone talking about ‘making meaning’ or ‘meaning-making’ is likely to be using resources from a whole language background. When referring to the process of reading, keywords like:

• sampling,

• noticing,

• reading behaviours,

• literacy events,

• authentic text,

• observation,

• word-solving,

• a range of strategies, and

• get your mouth ready

are also whole language red flags.

Next are the cute, but ultimately empty catchphrases that whole language proponents use to try and discredit structured literacy, especially systematic synthetic phonics:

• drill and kill

• talk and chalk

• reading is caught not taught

• barking at print

• all children learn differently

• no one size fits all

The most significant and endemic legacy of whole language is the Three-Cueing System (a.k.a. the Searchlight Model), methodologies based on the Reading Recovery program and the emerging balanced literacy movement.

In a disastrous misinterpretation of the underlying processes activated through reading, the Three-Cueing System has been developed, repeated and drummed into novice teachers since about 1986. It has no basis in science and runs counter to what we know about how words are lifted off the page (Adams 1998).

I am loath to give it oxygen, so in very brief summary, it is a (failed) model of the strategies children are supposed to use when reading words. It has developed into a system of coaching that downplays phonics, requires very little expertise and places the burden of learning to read on the child, the whole child and no one but the child.

Relying on oral language alone and using guessing – rather than decoding – is a dead end for many students. Cueing systems aside, whole language goes by several different names and has various guises, summarised below.

Guided reading

A small group approach where teachers attempt to use meaning and picture cues to get children to practise and read aloud a prescribed text. The text is usually selected based on the outdated and useless Running Records system of reading assessment, so even then, it is not appropriate reading material.

Pause, prompt, praise

Often used to try to guide parents listening to their children read, the pause, prompt, praise framework is just another way of trying to get children to connect to oral language without sounding out. The pause part is good, the prompt part is threadbare and the praise part is lovely but won’t help them develop a love of reading like it’s supposed to if they can’t actually decode the words.

Literacy levels

There are many systems in schools that place children into reading groups and in reading levels. In...