![]()

Part I

Historical styles and case studies from the Greeks to contemporary theatre

![]()

1 Embodying Greek period style

Physical dramaturgy in staging Euripides’ Medea

Chaya Gordon-Bland

Introduction

How do we transmit the sensibilities of a particular culture, time-period, and society, through centuries, and across geographies, to contemporary audiences? Dramaturgy, from the Greek dramatourgia: drama + ergos ‘worker,’ strives to address this challenge.1 Physical dramaturgy creates pathways by which the rich research, inquiries, and explorations of traditional dramaturgy can be transmitted into the actors’ bodies. The actors, who serve as the primary link between the audience and the world of the play, must fully absorb the fruits of dramaturgy, not only in their minds, but also in their bodies. When the actors corporeally understand, internalize, embody, and express the dramaturgical research, dramaturgy then succeeds, as it stimulates the audience’s intellect, imagination, and emotions. The world of the play is thus created both from the outside, via production elements, and from the inside, via the actor’s body, breath, and being; this is the work of physical dramaturgy. This chapter examines physical dramaturgy in the context of Greek period style, specifically as employed during a rehearsal process of Euripides’ Medea at the University of South Dakota. Through discussion of our questions, methods, challenges, and revelations, we unearth our process of transmitting dramaturgical research from the pages of the history book into the fibers of the actor’s being – and, ultimately, to our audience in a way that is relevant, compelling, salient, and alive.

Context and approach

This production, staged in fall 2012, engaged a cast of fifteen undergraduate performance majors and a design team comprised of faculty, graduate, and undergraduate students. Our production aesthetic emphasized strong reference and reverence to the historical circumstances of Ancient Greek theatre, but with an interest in creatively rediscovering, rather than archeologically reconstructing, the Greek theatrical world. The process began with traditional dramaturgical research into the history and given circumstances of the Ancient Greek world, followed by understanding and transmitting the aesthetics, style, and sensibilities of Ancient Greek theatre to the artists involved in the collaboration. The embodied research – the physical dramaturgy component – is the focus of this chapter. As production director, my approach to Greek period style is heavily influenced by the work of Jacques Lecoq and Michael Chekhov, both as distinct methodologies, and through exploring intersections and fusions (often unconventional) between these two approaches. In my teaching and direction, and consistent with Chekhov’s teachings, I emphasize and encourage strong connections between the actor’s body and her psychology, emotions, and inner life – a concept known as psychophysical connection.2 In order to support and encourage this holistic approach to expression, I frequently use the term ‘body-mind’ as I teach, direct, and write. Finally, this chapter is not a comprehensive overview of our full experience, but rather an attempt to shed light on key aspects of our process.

Historical givens

Ancient Greek theatre was markedly different from most 21st-century theatre experiences. Euripides’ dramatization of the Medea myth was first staged at the City Dionysia, the festival honoring Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, agriculture, fertility (and later, theatre) in 5th-century B.C.E. Athens. Here, plays were staged for an audience of roughly 15,000 people comprised of Greek citizens (and many servants) from throughout the nation. Gathering at the theatre each spring for the Festival of Dionysus was a special and heightened occasion. Situated within the context of a religious festival, the theatre of Ancient Greece had a highly ritualistic and ceremonial atmosphere. The use of masks, songs and dances of the Chorus, and a physically and energetically large performance style, further heightened the atmosphere.

Greek theatre also served a democratic function. The citizenry of the country would gather at this festival on the southern slope of the Athenian Acropolis seated in a semi-circular theatron (a place for seeing). The audience seating surrounded a full two-thirds of the orkestra (dancing space) – audience, Chorus, and heroic actors all shared the same natural lighting of the heavens.3 The tragic Chorus was comprised of citizens, not professional actors, selected for the honor of performing this important religious and civic function. The primary playing space for the Chorus, the orkestra circle, connected and overlapped with the seating of the citizens in the audience, reflecting spatially the Chorus’ civic role as bridge and mitigator between the theatrical and mythical worlds of the play and the contemporary world of the audience members. In 21st-century terms we might think of Ancient Greek theatre as containing elements of religious ceremony, judicial assembly, and a national sporting event – the scale and scope are vast, and can often seem to lie beyond the reach of today’s actors and audiences.

Physical dramaturgy: from intellectual understanding to embodied expression

The first week of our four-week rehearsal process was devoted to research, style work, and physical dramaturgy. Following dramaturgical research into the history and sensibility of Greek period style, we worked collectively to identify the particular stylistic demands of performing Greek tragedy. In our work, these included:

a The Actor’s Body: extension, economy, presence, and form;

b The Tragic Chorus: rhythm, ritual, unity, and breath;

c The Physical Dynamics of Tragedy: Jacques Lecoq’s “I am pushed/I am pulled;”4

d Heightened Language: finding the visceral life of the text.

We then embarked upon rehearsal exercises developed to help actors experience and achieve these specific sensibilities in their own body-minds, and to forge new connections, muscle-memories, and neurological pathways that would support and empower their performance of Medea.

Activating the actor’s body

The first set of exercises focus on developing ensemble, awakening the physical body, connecting body to breath, and discovering physical and emotional presence and size. We begin with simple games of ball tossing,5 designed to develop concentration, form, and ensemble connectedness. We then proceed with an exercise from Michael Chekhov’s work, the Awakening sequence,6 especially effective at connecting body to breath, exploring the full physical range of the body, and developing a sense of energetic size through the concept of radiating.7 These preparatory exercises lead us into a series of mask explorations, beginning with neutral mask.8 This mask, with its simple and smooth design, full-face coverage, and closed lips, is particularly effective at providing privacy and ease, transferring expression from the face and voice into the body, and connecting the actor more deeply to his creative impulses and inner experiences. Our first mask experience is Lecoq’s ‘Valley of the Giants,’ wherein the actors are asked to experience their bodies as if they are giants, and to move through the space as in an imaginary ‘valley of the giants.’ They are prompted to explore and engage with giant-sized (imaginary) objects in the space, and then to discover an activity or task in this valley that their giants need to accomplish. Once the task is established, the actors are then prompted to ritualize this task, and to perform it in a repeated fashion, as a ritual to the Gods. This exercise brings the actor a stronger awareness of her physical self, inspires physical and energetic grandeur, and leads to specificity, form, and ease. Experiences inside this exercise translate perfectly into the performance demands of Greek period style.

The next step is to progress from neutral to Greek masks.9 Unlike neutral masks, Greek masks reveal the lower jaw of the actor, contain specific information about character, and are designed with large, pronounced features, strong contours and lines, and emotional content. These masks inspire large physical and energetic size, a strong sense of character, and rich emotional impulses. After conducting research into the pantheon of Greek gods and goddesses, we brainstorm a list of Greek deities and their particular characteristics and traits; the list is placed in a visible place for easy reference during the next exercise. Actors are divided into two groups; half work in the masks while half observe. The first group selects masks in which to work, from a mixture of Gods, heroes, and citizens. I lead them through basic exercises of donning the mask, bringing body and breath into harmony with the mask, and finding the physical, vocal, and psychological life of the mask.10 Once the life of the mask has been established, the following ritual is enacted:11 mortals create an altar for the Gods (using simple rehearsal furniture), and then come before the Gods to make an important request. Each mortal has an opportunity to present themselves before the Gods, make their request, and plead their case; the Gods discuss each request, deciding whether to grant or deny. Once all of the requests have been heard, the mortals are dismissed. The improvisation ends with a moment alone for each mask/character to process what has just occurred. Through this improvisation, actors discover physical, vocal, and emotional size, slower tempo, greater specificity, high emotional stakes, and the significance of status, all crucial to the creation of the tragic Greek theatre.

Discovering the tragic Chorus: the living, breathing cell

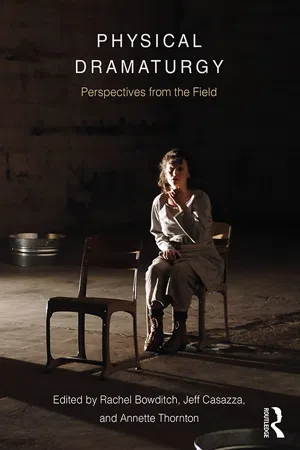

One of the most unique and poetic opportunities involved in staging Greek tragedy is the utilization of the tragic Chorus (Figure 1.1). Contemporary productions deal with the Chorus in a myriad of ways, sometimes conflating this group down to a few, or even a single actor, who then serve(s) as a type of narrator to the story. While this choice may help accommodate smaller production budgets, and perhaps achieve a more contemporary sensibility, it robs the production of the true richness of the tragic Chorus. Jacques Lecoq, the legendary movement teacher and theatre artist, held a particular interest in the tragic Chorus. His work and writings served as powerful inspiration for our creation process. In his book The Moving Body (Le Corps Poétique), Lecoq writes:

The chorus is the one essential element in clearing a genuine space for tragedy. A chorus is not geometric but organic. In just the same way as a collective body, it has its centre of gravity, its extensions, its respiration. It is a kind of living cell, capable of taking on different forms according to the situation in which it finds itself. […] But how are these people to be grouped? How can this collective body be brought to life? How can it be made to breathe and move like a living organism, avoiding both the aestheticized choreography and militaristic geometry? The chorus is one of the most important components of my teaching method and, for those who have taken part in one, it is the most beautiful and the most moving dramatic experience.

(130–131)

Figure 1.1 The tragic Chorus, Euripedes’ Medea. Directed by Chaya Gordon Bland, 2012. Photo courtesy of the University of South Dakota.

With Lecoq’s words and questions as our inspiration, we set out to discover together the organic, dynamic, and cellular nature of the Chorus. We begin with a discussion of the history of the tragic Chorus, recalling its roots in religion, ritual, and agriculture; the choral odes of Greek tragedy are believed to have stemmed from the dithyramb (circular dances), which were ritualistic songs and dances of prayer, and the orkestra (dancing place) of Ancient Greek theatre is believed to descend from the circular threshing floors used to thresh corn. The Chorus is intimately connected to the Earth.

We were additionally interested in pursuing a sense of lyricism and rhythm, unity and connectedness between Chorus members and audience, as well as individual identity for each woman within a unified collective. For our first exercise, we begin with ‘five minutes of nothing,’ wherein we lie on the floor in a relaxed, neutral position, and attempt to ‘do nothing.’12 This provides an opportunity to physically and mentally reboot, or ‘clear,’ to connect bodies to breath, to quiet the racing mind, and to fully arrive in the space together. Following ‘five minutes of nothing,’ we explore cellular breathing,13 wherein the actors experience the natural expansion and contraction/release that occurs in the body with each inhale and exhale. Next, we expand this sensation to the full physical body by ‘spoking through the planes,’14 physically expanding and releasing through the vertical, horizontal, and sagittal planes, allowing all of the movements to be fueled by the breath impulse while still on the floor. We further activate and mobilize breath and body by progressing from the floor to standing, and then to travelling through the full space. Next, actors are prompted to organically meet up with another actor, and move and breathe together. Each pair encounters another pair, and so on and so forth, until eventually the full group is moving and breathing together as one cell. The actors are then prompted to ‘radiate’ their movements, breath, and energetic bodies up to the Gods on Mount Olympus, further heightening the experience. This exercise connects the actor’s body, breath, and impulse together, connects actors to each other through a shared breath-shape and impulse, and exposes actors to the powerful beauty of non-verbal communication, connection, and physical expression, thus preparing for the work of the tragic Chorus.

Other ensemble exercises utilized to develop the Chorus include ‘Flock,’15 ‘Melting Sculptures,’16 and ‘Choral Orchestra.’ In ‘Choral Orchestra’ the group begins in a circle; one actor at a time creates a repeatable movement and sound, gradually adding in and layering upon the established sounds and movements, until the full group is involved and working harmoniously. Unlike the well-known theatre game ‘Machine,’ which tends to result in linear, mechanized sounds and movements, Choral Orchestra has a circular geometry. Instead of making physical contact with each other, as they do in ‘Machine,’ they connect to each other through rhythm and sound. Th...