![]()

1 Introduction

This is the fourth edition of my book on the international politics of the Asia-Pacific. The third edition was published only a few years ago in 2011, yet such has been the pace of change in global international relations and in the Asia-Pacific region in particular, that a new edition is required if the book is to meet the need for a more up-to-date analysis of the region as a whole. Previous editions were divided into two sections with the first focused on the Cold War period and the second on the changes since then. Although the legacy of the Cold War is still evident in this region, it is no longer the dominant force in driving regional developments. In fact, it has begun to recede into the historical memory. Only those aged 50 and older will have experienced the tensions of that period when the axis of conflict between the two systems led by the United States and the Soviet Union divided the world. This edition, like the second halves of the previous two editions has required writing a completely new account of the period since the demise of the Soviet Union in December 1991, but it also has required a total restructuring of the book. It will start with a reflection on the legacy of the Cold War, before launching a discussion into why the “new world order” envisioned by the first President Bush in 1990 failed to materialize and how it culminated in great uncertainty epitomized by the Trump presidency.

An overview of the Asia-Pacific region

The legacy of Western colonialism and imperialism shaped many aspects of the countries of the region, but what accounted for the emergence of the Asia-Pacific as a recognizable region in international politics was postcolonial modernization. The region has no antecedent existence as a coherent entity that can be identified prior to the 20th century. Yet, it was the birthplace of civilizations of great antiquity, namely China and India. However, there was little direct contact between the two. Southeast Asia was at the heart of maritime trade routes linking East Asia to Europe and Africa, yet despite its long history, rich in terms of distinct cultures and separate kingdoms some of which wielded great power, there was not a sense of a shared identity that linked them together as a collectivity, separate from others. The geographical terms and names including ‘Asia’ itself, are European in origin and the peoples of what has been called Southeast Asia since World War II did not have an equivalent name in any of the local languages. That, however, should not obscure the existence, long before the advent of the Europeans, of distinct varieties of statehood and patterns of relations between states, as can be seen from histories of the region and the many archeological remains.1 The imprints from the pre-European past are still evident in the present and, as will be argued later, they have presented barriers to the further integration of the region.

The Asia-Pacific could not have been conceived as a region before the different parts of the world were interconnected geopolitically, or before the different countries belonged to a system of states defined by sovereignty and territorial integrity, who shared various rules of conduct.2 Its emergence as a distinctive region was a product of several developments associated with the modernization and globalization of economic, political and social life that involved the spread of what might be called industrialism, and the rapid technological changes to which it gave rise throughout the world. Derived from Europe and still bearing the marks of their origin, these great forces shaped and continue to shape what we understand to be the contemporary Asia-Pacific. At the same time, their implementation in this part of the world has involved accommodation and adaptation to prior non-European traditions and institutions.

Only when the great powers began to treat the diverse countries of the region as a distinct area of international politics and economics did it become possible to identify the region with some sense of coherence. It was first treated as a separate geographical region at the Washington Conference of 1921–22, when the great powers of the day formally agreed to fix the ratio of warships they would deploy in the Pacific. That was designed to limit the geographic and military challenge of Japan – the first state in the Asia-Pacific to adapt to modernizing imperatives. By the 1930s, the Japanese had not only repudiated the agreement designed to restrict their naval deployments, but they also sought to exclude the Western powers altogether from the region. In the Pacific War, beginning in December 1941 with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese sphere of military operations also defined the sphere of the allied response. Several agreements among the Western wartime allies, beginning with the Atlantic Charter of 1941, followed by the Quebec Conference of 1943, which set up the South East Asian Command (the first time Southeast Asia had been officially recognized as a distinct geographical area), continuing with the Cairo Declaration of 1943 and culminating in the Yalta and Potsdam agreements of 1945, helped to shape the post–World War II distribution of power. They also contributed to provide parts of the region with greater geopolitical coherence. But they also marked the last time in which the region would be defined by the great powers to suit their interests without even informing local representatives, let alone consulting them.

The endogenous origins of the region as a distinct entity may be traced to Asian nationalist attempts in the 1920s and 1930s to throw off Western colonial rule. The Japanese described the empire they were establishing by conquest in the 1930s and early 1940s as “the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” Japan’s warfare left a legacy that transformed Asia in several ways. The memories of Japanese militarism and the magnitude of the atrocities committed by Japanese soldiers still shape Japan’s relations with several countries in the region and indeed the political identity of Japan itself. On perhaps a more positive note, the myth of Western racial superiority that was embedded in colonialism was irrevocably destroyed by Japan’s military victories and its humiliating treatment of the Europeans it had captured. On the eve of its defeat, Japan encouraged independence movements, especially in SE Asia, where nascent armies and guerrilla fighters were trained. Some of these went on to lead armed struggles against Europeans seeking to re-establish colonial rule, notably in Indonesia and Burma.

From a geographical perspective, the region may be defined in a broad fashion so as to include the littoral states of the Pacific Ocean of North, Central and South America; the island states of the South Pacific; Australasia; Northeast, Southeast and South Asia. From an economic point of view, the region could be restricted to the 21 economies that are members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, including 17 from Asia and four from the Americas (Canada, Chile, Mexico and the United States). From a political perspective, the region might be confined to the 18 members of the East Asian Summit, which includes India even though it does not border on the Pacific. Due to technological and geopolitical changes in the 21st century, which deepened India’s involvement in East Asian economic, maritime and political developments and China’s even deeper involvement in South Asian and India Oceanic affairs, the region is increasingly called the ‘Indo-Pacific.’

The complexities of the region

In order to keep this study manageable, the scope of the geopolitical coverage has been narrowed somewhat to include East Asia, the United States and India. An argument can be made for including Central Asia, but the sub-region is on the periphery of the Asia-Pacific, it lacks a maritime presence and it is a recipient of occasional interest by others, rather than an active initiator of ideas and issues that could shape the development of the region. The same could be said to a large extent of parts of South Asia or the Indian Ocean region other than India. Other components of what may legitimately be regarded as belonging to the Asia (or Indo) Pacific, namely Canada, parts of Latin America, Australia, New Zealand and the islands of the South Pacific will be included only when necessary to explain the international politics of others in the region.

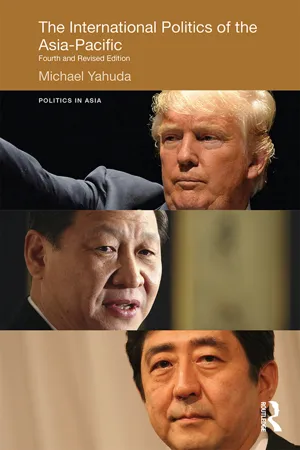

Regional developments have been shaped largely by the three great powers: The United States, China and Japan. Their significance will be considered in separate major chapters. India, as the emergent great power, has yet to make its own independent major contributions to the development of the region as a whole. Its importance in the region will be addressed in the other chapters in a more piecemeal fashion. Russia is often said to be a resurgent power, but that may apply to the roles it plays in Europe, Eurasia and perhaps in the Middle East. Its role in this region is limited and it will be treated in the other chapters as appropriate.

The geographic character of the region encompasses much variety and complexity from the near Arctic conditions in the far north to the tropical monsoon conditions near the equator and from the coastal plains of much of East Asia to the deserts of Central Asia and the high mountains of the Himalayas, the Pamir and the Mountains of Heaven. The differences between the resident states vary from, at one extreme, China, with a territory of more than 9,561,000 square kilometers and a population of 1,378,000,000 to the other extreme, Singapore, with a territory of only 625 square kilometers and a population of 5.6 million. The two countries also serve to point up further disparities in terms of the economies: With a GDP of US$11.199 trillion, China ranks second in size only to the United States, and it is more than 37 times larger than that of Singapore’s US$297 billion; but in per capita terms China’s GDP is US$8,123 compared to Singapore’s $52,961.3 As can be seen from these World Bank (WB) figures, China has just reached what the WB classifies as an upper middle income country (US$7,937), whereas Singapore is very much in the WB’s high income range (US$40,677).4 The economic disparities of the region would loom even larger if Japan were to be compared with Vietnam or Burma/Myanmar.

Geographic differences within and between countries can also have profound implications, some of which may have been obscured by advances in technology, especially those of transport and communications. For example, until the modern era, the Himalayan Mountains and the Tibetan plateau effectively separated the great civilizations of India and China for thousands of years, except for a few intrepid monks and merchants. That did not stop the transfer of Buddhism and ideas, but it was only with the advent of modern technology that mutual relations opened up. Even so, the high mountains still remain a formidable, if no longer an insurmountable, barrier. Other geographical features have influenced communications, cultural outlooks and economic and political relationships. These include maritime locations, effects of climate, the location of arable land and its proportion to the total land area of the country, and so on. Consider, for example maritime issues: As an island country, Japan was on the periphery of the Sinitic world and, although heavily influenced by Chinese culture, its traditional political system was feudalistic (as in Europe) rather than bureaucratic (as in China, Korea and Vietnam). In the contemporary era, Japan has the option of drawing attention to its maritime identity with an orientation of itself towards the Pacific Ocean as well with its cultural and historical common heritage with continental East Asia, or at least of finding a congenial balance between them.5 Taiwan’s continued separation from the Chinese mainland has only been possible because it is an island about 100 miles away from China. Another example is the often-noted differences between continental and maritime Southeast Asia. Among these differences are the former’s closer links with China, from ancient times to the present, and the latter’s trading antecedents, which orient them more easily to regarding their positions as a bridge between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

In addition to these geographic and economic factors, the region is characterized by great variations in cultures, religions, historical associations, social traditions, language, ethnicity and political systems. Many of these divisions can occur within the same country and often cut across state boundaries. These make for tensions between states in the region, exacerbate the problems of nation building and the consolidation of state power from within. This is particularly true of the states of Southeast Asia, where the colonial experience promoted links with the metropolitan power in distant Europe rather than with Asian neighbors. The Indo-Chinese states were tied to France; Burma, as part of the British Raj, was oriented to Britain, as were Malaya and Singapore (separately from India); Indonesia, however, was attached to Holland (with the island of Borneo divided between the Dutch and the British). The Philippines was under Spanish rule until 1898, when it was taken over by the United States, which attempted to remake it in the American image. Some of the states were actually creations of the colonial powers, with their boundaries reflecting colonial interests and the character of relations between them, without taking into account local views and realities.

Map 1.1 The Asia-Pacific Region

Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, in their present forms, do not have precise antecedents, although their nationalist elites draw on pre-colonial traditions. At the same time, the borders, which all Southeast Asian states inherited from the colonial era have left most of them with territorial disputes with neighbors. The colonial legacy has also given rise to highly complex domestic communal problems, highlighted, for example, by the ethnic Chinese. Many came as indentured laborers or as economic migrants to benefit from working or trading under what they regarded as beneficial colonial conditions, but after their resident states gained independence they often found new difficulties in being accepted as loyal trustworthy citizens. There were other groups who were located in countries where they were conspicuously different from the ethnic majority and also had different religious beliefs. Such was the case, for example, with the Muslim Malays in the three southern provinces of Buddhist Thailand, which bordered Malaya.

New states have found that their historical legacies from both the pre-colonial eras and the colonial period are complex and subject to much dispute as they necessarily involve questions of defining modern national identities, for which there are few antecedents. Even where states can claim a premodern existence, the character of statehood has changed beyond recognition. That has given rise to debates about relating contemporary political concepts and structures to those of the past, with practical consequences for the conduct of domestic politics and for relations with neighbors. The advent of the Europeans introduced concepts of sovereignty, territorial integrity, citizenship, international law, legal equality between sovereign states and so on, which have all become incorporated into the structures and operations of the states of the region. The states of the region are either new or created afresh on older forms. Many do not take their independence or the continued existence of their forms of government for granted and their apparent self-confidence often conceals a sense of vulnerability.

The erosion of the liberal international order

The main argument of this fourth edition is that the international structure based on American predominance in the early post–Cold War years has gradually eroded without being replaced by an effective alternative, which is currently characterized by disorder and uncertainty. Seven years ago, I had argued that despite remaining the sole superpower, the United States had been “unable to reshape the world in accordance with its vision of free markets and democratization.” Today, as the year 2018 draws to a close, the situation is much worse: There is neither order nor agreement among the major powers as to how a new order might be structured or how the old liberal one might be revived, or indeed whether it should be revived. The main pillars of the old liberal international system, the European Union and the United States, are deeply divided and challenged by new populist and nationalist political parties. Externally, they confront a new wave of autocracy headed by the two great powers, China and Russia, who seek to revise the old order by undermining its values and by expanding their power and influence. In practice, the two dictatorships observe only those international norms and rules which suit their interests, and ignore, revise or oppose those which stand in their way. The advent of the Trump presidency in the United States comports with current nationalist and populist trends elsewhere. The kind of international relationships he has envisioned would be based on unilateralism and bilateral arrangements, as opposed to multilateral agreements. Trump declared his credo to the annual summit meeting of the 21 members of APEC in November 2017: “I am always going to put America first, the same way I expect all of you in this room to put your countries first.”

Three days after taking office on January 20, 2017, President Trump turned his back on the old liberal multilateral order by abruptly announcing his country’s withdrawal from the TPP (the Trans-Pacific Partnership). This was a multilateral trade agreement among 12 countries designed not only to reduce tariffs but also to overcome non-tariff barriers and ensure fair competi...