![]()

Part 1

Punitive Trends

![]()

1. The great penal leap backward: incarceration in America from Nixon to Clinton

Loïc Wacquant

In 1967, as the Vietnam War and race riots were roiling the country, President Lyndon B. Johnson received a report on America’s judicial and correctional institutions from a group of government experts. The Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice related that the inmate count in federal penitentiaries and state prisons was slowly diminishing, by about 1 per cent per annum (President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967). That year, America’s penal establishments held some 426,000 inmates, projected to grow to 523,000 in 1975 as a by-product of national demographic trends. Neither prison overcrowding nor the inflation of the population behind bars was on the horizon, even as crime rates were steadily rising. Indeed, the federal government professed to accelerate this downward carceral drift through the expanded use of probation and parole and the generalization of community sanctions aimed at diverting offenders from confinement. Six years later, it was Richard Nixon’s turn to receive a report on the evolution of the US carceral system. The National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals noted that the population under lock had stopped receding. But it nonetheless recommended a ten-year moratorium on the construction of large correctional facilities as well as the phasing out of establishments for the detention of juveniles. It counselled shifting away decisively from the country’s ‘pervasive overemphasis on custody’ because it was proven that ‘the prison, the reformatory, and the jail have achieved nothing but a shocking record of failure. There is overwhelming evidence that these institutions create crime rather than prevent it’ (National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, 1973: 597).

At about the same time, Alfred Blumstein and his associates put forth their so-called homeostatic theory of the level of incarceration in modern societies. According to the renowned criminologist, each country presents not a ‘normal’ level of crime, as Emile Durkheim had proposed a century before in his classic theory of deviance, but a constant level of punishment resulting in a roughly stable rate of penal confinement outside of ‘severely disruptive periods like wars or depressions’. When this rate departs from its natural threshold, various stabilizing mechanisms are set into motion: the police, prosecutors, courts, and parole boards adjust their response to crime in a permissive or restrictive direction so as to redraw the boundary of deviant behaviours subjected to penal sanction, adjust sentences, and thereby reduce or increase the volume of people behind bars. The proof for this view was found in time-series analyses of the feeble oscillations of the imprisonment rates revealed by US statistics since the Great Depression and by Canadian and Norwegian statistics since the closing decades of the nineteenth century (see Blumstein and Cohen, 1973; Blumstein et al., 1977; see also Zimring and Hawkins, 1991).

As for the revisionist historians of the penal institution, from David Rothman to Michael Ignatieff by way of Michel Foucault, they substituted a strategic narrative of power for the humanistic trope of enlightened reform and painted imprisonment not merely as a stagnant institution but as a practice in irreversible if gradual decline, destined to occupy a secondary place in the diversifying arsenal of contemporary instruments of punishment. Thus Rothman concluded his historiographic account of the concurrent invention of the penitentiary for criminals, the asylum for the insane, and the almshouse for the poor in the Jacksonian republic by sanguinely asserting that the United States was ‘gradually escaping from institutional responses’ so that ‘one can foresee the period when incarceration will be used still more rarely than it is today’ (Rothman, 1971: 295; see also Ignatieff, 1978). For Foucault, ‘the carceral technique’ played a pivotal part in the advent of the ‘disciplinary society’, but only inasmuch as it became diffused throughout the ‘social body as a whole’ and fostered the transition from ‘inquisitory justice’ to ‘examinatory justice’. The prison turned out to be only one island among many in the vast ‘carceral archipelago’ of modernity that links into a seamless panoptic web the family, the school, the convent, the hospital, and the factory, and of which the human sciences unwittingly partake: ‘In the midst of all these apparatuses of normalization which are becoming tighter, the specificity of the prison and its role as hinge lose something of their raison d’être’ (Foucault, 1978: 306; my translation).

Spotlighting this tendency towards the dispersal of social control exercised by the state, the radical sociology of the prison hastened to denounce the anticipated perverse effects of ‘decarceration’. Andrew Scull (1977) maintained that the movement to release inmates, from behind the walls of penitentiaries and mental hospitals alike, into the community worked against the interests of deviant and subordinate groups by giving the state licence to unload its responsibility to care for them. Conversely, Stanley Cohen (1979) warned against the dangers of the new ideology of the ‘community control’ of crime on grounds that diversion from prison at once blurs, widens, intensifies, and disguises social control under the benevolent mask of ‘alternatives to imprisonment’. These academic critiques were echoed for the broader public by such journalistic exposés as Jessica Mitford’s portrait of the horrors of America’s ‘prison business’ and of the ‘lawlessness of corrections’, leading to the denunciation of further prison building as ‘the establishment of a form of legal concentration camp to isolate and contain the rebellious and the politically militant’ (Mitford, 1973: 291).

In short, by the mid-1970s a broad consensus had formed among state managers, social scientists, and radical critics according to which the future of the prison in America was anything but bright. The rise of a militant prisoners’ rights movement patterned after the black insurgency that had brought down the Southern caste regime a decade earlier, including drives to create inmates’ unions and to foster convict self-management, and the spread of full-scale carceral uprisings throughout the United States, followed by their diffusion to other Western societies (Canada, England, France, Spain, and Italy), powerfully reinforced this shared sense of an institution mired in unremitting and irretrievable crisis.1

The great American carceral boom

Yet nothing could have been further from the truth: the US prison was just about to enter an era not of final doom but of startling boom. Starting in 1973, American penal evolution abruptly reversed course and the population behind bars underwent exponential growth, on a scale without precedent in the history of democratic societies. On the morrow of the 1971 Attica revolt, acme of a wide and powerful internal movement of protest against the carceral order,2 the United States sported a rate of incarceration of 176 per 100,000 inhabitants – two to three times the rate of the major European countries. By 1985, this rate had doubled to reach 310 before doubling again over the ensuing decade to pass the 700-mark in mid-2000 (see Table 1.1). To gauge how extreme this scale of confinement is, suffice it to note that it is about 40 per cent higher than South Africa’s at the height of the armed struggle against apartheid and six to twelve times the rate of the countries of the European Union, even though the latter have also seen their imprisonment rate rise rapidly over the past two decades. During the period 1985–1995, the United States amassed nearly one million more inmates at a pace of an additional 1,631 bodies per week, equivalent to incorporating the confined population of France every six months. As of 30 June 2000, when runaway growth finally seemed to taper off, the population held in county jails, state prisons, and federal penitentiaries had reached 1,931,000 and crossed the two-million milestone if one reckons juveniles in custody (109,000).

Table 1.1 Growth of the carceral population of the United States, 1975–2000

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850–1984 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1986); ibid, Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2000 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 2001).

There are three main types of carceral establishments in the United States. The 3,300 city and county jails house suspects brought in by the police, awaiting arraignment or trial, as well as convicts in transit between facilities or sanctioned by terms of confinement inferior to one year. The 1,450 state prisons of the 50 members of the Union hold felons sentenced to terms exceeding one year, while those convicted under the federal penal code are sent to one of the 125 federal prisons, irrespective of the length of their sentence. Each sector possesses its own enumeration system, which explains discrepancies in the data over time (including when they come from the same source). This census excludes establishments for juveniles, military prisons (which held 2,400 inmates at end of 2000), facilities run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (8,900), prisons in US overseas territories (16,000), and jails in Indian reservations (1,800). It also omits police lock-ups, which are more numerous than jails (in 1993, 3,200 police departments operated one or more such facilities with an average capacity of ten detainees).3

One might think that after 15 years of such frenetic growth American jails and prisons would reach saturation and that certain of the homeostatic mechanisms postulated by Blumstein would kick in. Indeed, by the early 1990s, federal penitentiaries were officially operating at 146 per cent of capacity and state prisons at 131 per cent, even though the number of establishments had tripled in 30 years and wardens had taken to systematically ‘double-bunking’ inmates. In 1992, 40 of 50 states and the District of Columbia were under court order to remedy overpopulation and stem the deterioration of conditions of detention on pain of heavy fines and prohibitions on further incarceration. Many jurisdictions took to hastily releasing thousands of nonviolent inmates to disgorge their facilities and over 50,000 convicts sentenced to terms exceeding one year were consigned to county facilities in 1995 for want of space in state prisons.

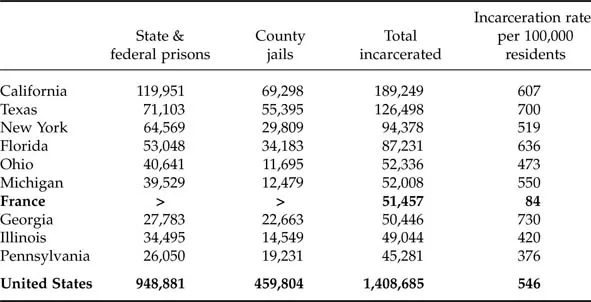

But America’s carceral bulimia did not abate: at the end of the single year 1995, as Clinton prepared to campaign for re-election on a platform of ‘community, responsibility, and opportunity’ buttressed by the ‘end of Big Government’, an additional 107,300 found themselves behind bars, corresponding to an extra 2,064 inmates per week. Eight states had seen their carceral population grow by more than 50 per cent between 1990 and 1995: Arizona, Wisconsin, Georgia, Minnesota, Mississippi, Virginia, North Carolina, and Texas, which held the national record with a doubling in a short five years. As early as 1993, six states each counted more inmates than France (see Table 1.2). California, with 32 million inhabitants, confined nearly as many as the eleven largest continental countries of the European Union put together. Georgia, with a mere seven million residents, had more inmates than Italy with 50 million.

Table 1.2 The states leading carceral expansion in 1993

Sources: For city and county jails, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail and Jail Inmates 1993–94 (Washington, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1996) for federal and state prisons, idem, Prisoners in 1993 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1994; Printing Office, 1995); for state populations, estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, available on line.

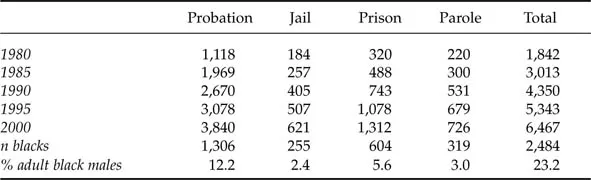

And this is but the emerging point of the American penal iceberg. For these figures do not take account of offenders placed on probation or released on parole after having served the greater part of their sentence (typically 85 per cent by virtue of federal ‘truth-in-sentencing’ mandates). Now, their numbers far surpass the inmates count and they too increased steeply following the penal turnaround of the mid-1970s. Between 1980 and 2000, the total number of persons on probation leapt from 1.1 million to 3.8 million while those on parole shot from 220,000 to nearly 726,000. As a result, the population placed under correctional supervision approached 6.5 million at the end of this period, as against 4.3 million ten years earlier and under 1 million in 1975. These 6.5 million individuals represent 3 per cent of the country’s adult population and one American male in 20 (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Population under correctional supervision in the United States in 2000 (in thousands).

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2000 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2002), p. 2 and Census Bureau estimates of US population by race and age.

Breaking that figure down by ethnicity reveals that one black man in nine today is under criminal oversight. We will indeed se...