Chapter 1: ART, CULTURE, AND HYBRIDITY

ART HAS THE CAPACITY to be both a record of its time and an expression of universal human values. These values can be related to many sources: individual and group identities; ethical, religious, and political systems; and the experiences of sexuality and gender in addition to aesthetic values. An orientation toward art as a record of its time means taking a cultural approach to art. But we can also respond to art as expressive of universal human values not tied to any particular place. This contrast between the particular and the universal may be felt as a tension, perhaps even as a conflict. Does the local, cultural importance of art cancel out the universality of aesthetic expression and judgment? Conversely, when we respond in a general, intuitive way to the art of distant periods and cultures, do we downplay the importance of specific cultural contexts? An alternative to thinking of these views as conflicting is to view them as complementary. Perhaps art has the unique capacity to express the universal through the particular. Why is this the case? How are general aesthetic values revealed through specific cultural expressions? We need to explore this relationship between art and culture before considering how art can have an intercultural function. Establishing connections between culture and art is a necessary first step in a discussion of intercultural issues in art.

Culture has at least two distinct meanings. One is the anthropological meaning of the term that refers to the unifying characteristics of a group of people; these may include geographical proximity; shared language, intellectual, and artistic traditions; kinship, religious, economic, or political systems; and so on. Culture refers to those circumstances, worldviews, and habits of life that distinguish a group of people from other groups. In this sense, art is one of a number of processes that make up a culture's distinctiveness. Art and design can be understood more fully when viewed in relationship to these other processes.1

In this anthropological framework, culture is a concept that can be approached from many levels. We may associate cultures with broad geographical regions: East Asian, Southeast Asian, West African, South African, Western European, and so on. These are recognized as culture areas because of the geographical proximity of cultures in these areas, their shared linguistic patterns, similarities in worldviews, common trade networks, and so forth. Or one can consider culture at a micro-level: Students who like metalcore music, certain styles of dress, and similar movies in a high school may form a definable subculture within that setting. Even though culture can be understood from many levels, the concept of levels does not imply valuation or ranking; and no individual culture is seen as inherently better than another. The anthropological understanding of culture is analytical, because it isolates the components of culture and considers their relationships to each other. But, it is not evaluative, because it does not “rank” cultures according to a general notion of progress.

In recent years art history as a discipline has adopted this analytical understanding of culture. In research methodology, anthropology and art history often focus on statements by the members within a society, compile many descriptive observations, and then use this evidence to answer theoretical questions. Artistic expressions by varied groups are a way to understand cultural differences without making value judgments as to whether one culture's expression is better than another's. When analyzing a broad range of cultures and considering individual cultures from an insider's or “emic” perspective, the artistic products of varied cultures are seen as equal in importance or value. However, this has not always been the case. In the past, art historians have bestowed privilege on particular artists, cultures, and periods. One could argue that, in their choices about what to analyze (and what to ignore), historians have made value judgments about the importance of particular artists, cultures, or periods. This ranking of the importance of art within particular contexts points to a second meaning of culture.

In this second meaning, culture refers to the practices, tastes, and values associated with particular social classes. To “have” or “get” culture implies that some activities are valued more than others by a group of people and, therefore, these activities should be pursued. Sometimes there seems to be an intrinsic value attached to high culture in the West. High culture refers to those artistic products that have traditionally been held to be of high artistic merit and importance. In the West, an orchestral performance of a symphony by Beethoven or a painting by Leonardo da Vinci is an example of high culture. Similarly, in some contemporary Native American groups, culture refers to specific traditional practices, such as drum groups, storytelling or totem carving, that are being consciously preserved and renewed for specific social purposes. In this second sense of the term, then, culture refers to the values that we place on some artistic expressions as worthy of public recognition and support. Because this is a value-based definition, not everybody will agree on the relative value of kinds of expression. For instance, someone might feel that movies are more valuable than performances by symphony orchestras. But, even in this case, a value judgment about a cultural expression is being made, even though the commonly assumed relationship between high and low culture has been inverted.

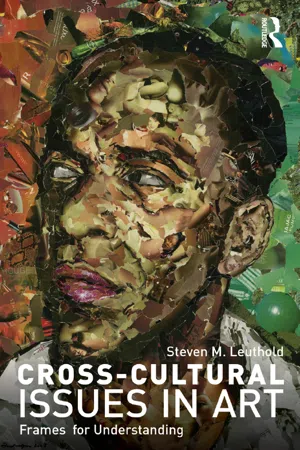

It is not a problem that value-based judgments exist along with analytical understandings of culture, as long as these two understandings are acknowledged and discussed in relationship to one another. In the past, some researchers have acted as if their actions were value free. But choices related to subject matter and methods of study are usually based upon personal and culturally based values. Similarly, artists often investigate the art of other cultures because of the evaluative dimension that this research has for their own creative process. A good example of how values are a significant aspect of cross-cultural investigation by artists is found in the controversial work, Holy Virgin Mary (1996) by the Afro-British artist, Chris Ofili.

His Virgin famously included a piece of dung attached to the surface of the Virgin's breast, and this, along with the image's overt sexual references, drew the ire of religious groups. But, the sensuality of traditional images of the Virgin was the value that motivated Ofili:

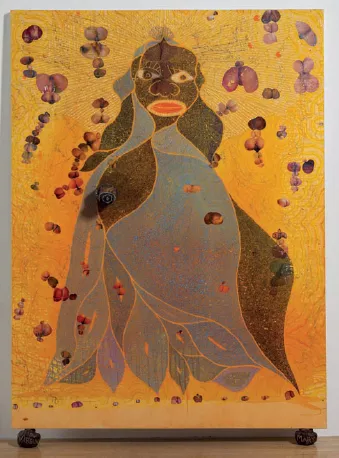

Figure 1.1 Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996. © Chris Ofili. Courtesy of the Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Photo taken by Stephen White. Reproduced with permission.

I was going to the National Gallery, Sainsbury Wing and looking at Van Eyck's paintings of mother and child. I just wanted the image of the breast really. The exposed breast is hinting at motherhood but those images are very sexually charged. She's painted as this beautiful, passive, angelic woman, pure and very attractive looking. I think the Virgin Mary was an excuse for pornography in the homes of these holy priests and God fearers. So I think in the ′90s a version of it would allow the pornographic images to come more to the surface . . . I think it's a very beautiful painting to look at, full of contradictions, which is perhaps why it's been misunderstood.2

Ofili explores the overtly sensual values that mark contemporary society (which he calls pornographic) by finding an unexpected source for them in earlier artistic traditions. His work uses cultural differences—contemporary/historical, European/African—as a way to investigate the values that he feels are communicated through an artistic tradition. One of the cultural differences at play is that in some African societies, elephant dung has sacred meanings, whereas in most Western cultures, dung—or shit—is seen as dirty and associated with desecration. Both the analytical and evaluative dimensions of culture are at play in his work. What, then, is the relationship between these two ways of understanding culture?

The anthropological understanding of culture leads to a position known as cultural relativism, the belief that every society, regardless of its size, is an integrated whole in which values make sense within the context of that culture. In this sense, the concept “primitive” (which is often taken to be problematic in recent times) simply refers to a low degree of economic specialization, the use of simple rather than complex technologies, a relatively small, sparse population, and so on. There is no value judgment tied to the term; it merely describes a related set of social characteristics. Cultural relativism downplays the notion that there are common cross-cultural properties of art. Rather, art and design are created and experienced within a specific context. Relativism carries a sense of responsibility that to understand the expressions of other cultures in their context, one must not impose one's own views and values on these expressions. Contextualism is a useful way of thinking because it helps explain cross-cultural differences in aesthetic experience and judgment. However, if one takes the idea of context to the extreme, the logical outcome is total relativism. This position would state that only members of a particular culture are able to truly understand or make judgments about the products and experiences of that culture. But is this really the way that we experience the world, or do we, in fact, often have assumptions and make judgments that have cross-cultural value? Ofili's analysis and re-creation of the Virgin is an example of one instance of cross-cultural interpretation and judgment. But those who objected to his vision were also offering a strongly stated opinion as to the value of a tradition that has origins in a culture much different than the present (even though aspects of that cultural tradition remain alive today). Though there were many, the most well-known critic of the painting, and of the museum for showing it, was the mayor of New York:

Ten days prior to its opening, Giuliani pronounced the exhibit “sick” and promised to withhold the museum's $7.2 million in city funding—about a third of the Brooklyn Museum's budget—unless the show was canceled. Giuliani didn't object to the exhibit's being seen, just to the fact that it was being paid for with tax money. “You don't have a right to government subsidy for desecrating somebody else's religion,” he said. Other Republicans only talk about fighting the culture war; Giuliani is actually in the trenches. Later, he said he would disband the museum's board of directors, and the city filed a lawsuit contending that the museum had violated its lease.3

The words, sick, desecration, and culture war in the previous story demonstrate just how value-laden responses to cross-cultural artistic expressions can be.

However, what happens when one steps back from a specific context, such as Brooklyn in the late nineties, and looks for cross-cultural patterns? Let us return to that troublesome term “primitive.” There seem to be pairs of contrasting categories embedded within the idea, such as simplicity/complexity or tradition/progress, that are applicable cross culturally. We may understand the “primitive” as simple—technologically, economically, socially, etc.—in comparison to complex or developed cultures. In the comparative process, categories embedded in our analytical framework come to the fore, and we assume that these categories are more general than their application to any one context. Is it going too far to say that the contrasting terms, simplicity and complexity, do have universal implications for our understanding of culture (and of art)? In contrast to the relativism inherent in a contextual approach, an attempt to discover underlying assumptions that frame intercultural study leads to “universals” of aesthetic thought and experience. These cross-cultural terms, such as simplicity and complexity, are sometimes referred to as absolutes of aesthetic experience because they are applicable to all expressions within all cultures. In addition, subjects such as those pertaining to male/female themes or the relations of young and old are found in all cultures. These can be contrasted with culture-specific themes; for instance, the concept of democratic participation in the arts is specific to certain cultures. In most cultures, art has been created for very specific and powerful patrons.

Aesthetics is the discipline that is traditionally concerned with fundamentals—absolutes—concerning the nature and value of art. But the attempt at defining art and other dimensions of aesthetic experience cross culturally seems to go against the very idea of cultural relativism. How can there be so-called universals if we have already established that aesthetic experience is highly contextual? How can one solve this difficult problem? One could solve it by doing away with any attempt at a common understanding of art, but the problem does not go away that easily because we have to somehow define that which in other cultures can be called “art.” In other words, even in choosing a starting point one seems to instinctively apply an aesthetic universal, art. A first problem of aesthetics, then, is defining art itself. What definition of art does one assume and use for comparative or intercultural purposes? Is there a universal definition of art applicable across cultures?

In an ideal scenario, it would be better not to start out with one's own everyday conceptual biases in viewing the art of other cultures. But there are frameworks for viewing, embedded in the Western understanding of the term art, which will color the very selection of that which is recognizable as art in other cultures. Presently, in Western cultures art often (a) is something valued for properties beyond the practical function of the thing, (b) has sensuous or intellectual appeals that make it stand out, (c) reflects the skill and/or creativity of the maker (which are more developed than the skill or creativity of others), (d) is exhibited or performed in spaces designated for the purpose of displaying art, and so on. Are any of these common to the experience of art in other cultures? Or are there very different arts, so different, in fact, that “art” itself may be a term that has little value?

Some of the social dimensions of art just mentioned, such as where, when, and how art is displayed or performed, will vary widely between cultures. But symbolic expression, which is at the heart of artistic creativity, is common to all cultures. In the past, some theorists hypothesized that humans are unique as symbol-producing animals. This view follows from the symbolic theories of the German philosopher, Ernst Cassirer, who wrote that symbolization forms the core of all activity that is uniquely human. More recently, scientists have discovered that other primates have symbol-making capacities. But the fact that symbolizing is shared with other animals need not devalue these processes. Symbolic expression goes to the very heart of our reason for living. Why do we live: perhaps because of the symbolic values that we attach to life? Since art is one major aspect of symbolic expression, art is part of what makes life worthwhile for all people. Though it is dangerous to apply a single, closed definition of art cross culturally, there seems to be ample evidence for considering the universality of symbolic expression as a defining feature of art.

Another basis for claiming that there are universal, cross-cultural dimensions of aesthetic appreciation is biological. All humans share certain cognitive and perceptual capacities because of their shared biological structure, specifically the biology of the brain and nervous system. “Scientific findings about the laterality of the brain proved that perception and cognition are, indeed, functions of the brain.”4 The theorist, Paul, has even argued that beauty, a maligned concept for much of the past century, may have a basis for existence in both philosophical aesthetics and recent scientific research into the brain. One of the traits of human perception is selection, and good artists are highly skilled in appealing to the selective nature of human perception. Those processes of perception, identified as early as the 1920s by the Gestalt psychologists, can be taken not only as a description of perception but also as a list of biases that humans universally favor: the tendency to see a figure in contrast against a ground, the bias toward distinct forms such as geometrical figures, the bias toward order in the arrangement of visual units. Again, these are general properties of human perception and, therefore, trans-cultural.

Thus, an understanding of the relationship between art and culture involves a back-and-forth movement between two poles of thought, the contextual and universal. Comparative study could easily lead to too heavy an emphasis on either pole. Limitation to either of these poles would lead to radical relativism on the one hand, or philosophical absolutism on the other. Neither of these positions would accurately reflect the way in which lives are actually led. Most often people live and think between the poles of the relative and the absolute. In many instances, the experience of one pole is used to test the validity of the experiences of the other. Rather than canceling each other out, each pole helps us qualify and understand the other. This, then, is the motion of this book, the constant testing of the general by the particular and the particular by the general. And that is also the nature of the comparative method, to search for universals such as “form,” “beauty,” and “truth” in the particularity of the everyday aesthetic experiences of more than one culture.

Where all of this becomes problematic, though, is in the domain of aesthetic judgment. It is one thing to acknowledge the poles of the universal and relative for analytical purposes; it is another to acknowledge them for questions of value. We may understand the primitive as intrinsically “better” than more complex cultures because the primitive is more “pure” or close to the essence of human experience. Or we may understand the primitive as “inferior” to complex cultures because it is, by definition, backward, or lacking in technological progress. This contradiction in valuative terms points to the modern experience of primitivism. In contrast to the objective detachment associated with cultural relativism, the comparative process points out the valuative dimensions of judgment that cut across cultural boundaries. Sometimes, these dimensions are referred to as normative because they imply standards (norms) that artworks ought to meet in order to be valued as exhibiting high quality. Are there standards of quality by which artworks can be judged? Do these standards apply cross culturally in any way?

This idea—that there are cross-cultural dimensions that we use to understand, and judge, artistic experience—can be seen in the process of defining and implementing standards of artistic quality. From the perspective of cultural relativism, the idea that quality can be defined and applied cross culturally is highly troubling. In culturally relative schemata, standards of quality are defined and experienced according to the internal dynamics of a culture. Thus, reformers have called for a decentralizing of judgments of artistic quality. However, every day curators, collectors, writers, teachers, and artists make judgments about the quality or importance of artworks produced in other cultures. Often, the judgments are made in the process of selection: what should or sh...