![]()

1 The context of arts marketing

This chapter sets the context for the chapters which follow. In it we will examine the nature of the arts, and consider some of the tensions that arise within the arts environment, and in the relationship of the arts to a broader social and economic context. We will then turn our attention specifically to arts marketing, as part of a wider arts management function, flagging up some key issues facing arts marketers. Marketing the arts involves not only the day-to-day work of attracting audiences to events and activities, but also the need to understand and promote more widely the value of an organization’s work.

The issues we will address are:

• Definitions of the arts and of arts marketing

• Cultural policy and ‘value’ in the arts

• Future perspectives on arts marketing – theory and practice

• The arts marketing environment

• Key issues and problems in arts marketing

• Arts marketing and ethics

What are the arts?

One of the difficulties of analysing the environment for arts marketing is the diversity of activity covered by the arts. A popular and inclusive definition was provided by the 89th US Congress, and later endorsed by what was then the Education, Science and Art Committee of the UK House of Commons:

The term ‘the arts’ includes, but is not limited to, music (instrumental and vocal), dance, drama, folk art, creative writing, architecture and allied fields, painting, sculpture, photography, graphic and craft arts, industrial design, costume and fashion design, motion pictures, television, radio, tape and sound recording, the arts related to the presentation, performance, execution and exhibition of such major arts forms, and the study and application of the arts to the human environment.

(Arts Council of Great Britain, 1993)

Since the 1990s a whole category of digital art has been added to this list with the proliferation of new technologies. Definitions such as this are not just a case of hair-splitting pedantry. Definitions of culture, art forms or the nature of artistic activity can vary significantly from country to country and even, within countries, between organizations. Given the complexity of defining what art is, it then becomes difficult to be clear about the scope of arts marketing activity.

Box 1.1 A definition of art

Art is a documented expression of a sentient being, through or on an accessible medium, so that anyone can view, hear or experience it. If this solidified expression, or the act of producing it, is ‘good’ or has value depends on those who access and subjectively rate it.

Source: adapted from Wikipedia.

In 1995, when the first edition of this book was published, the discipline of arts marketing was relatively new. Practitioners and advocates for an integrated marketing approach had to argue against a persistent scepticism towards marketing, which was widely believed to be an inappropriate import from the business world into an arena which was essentially driven by moral and aesthetic, rather than commercial, values. In more than 20 years, the field of arts marketing has developed immeasurably. As the discipline of arts marketing has become increasingly sophisticated in practice, this sophistication has been matched by an explosion of academic research which engages critically with all aspects of cultural policy, arts consumer behaviours and the theories of arts marketing which underpin practice. This chapter can only engage lightly with these critical debates and point the reader towards some of the journals and researchers who are active in the field. That this is an eclectic field cannot be denied, with links to broader fields such as cultural policy, cultural economics, sociology and technology as well as, obviously, business (O’Reilly, 2011).

As a working definition, we can say:

Arts marketing is an integrated management process which sees mutually satisfying exchange relationships with customers as the route to achieving organizational and artistic objectives.

Art for art’s sake: artistic ends and marketing means

In this chapter, we look in particular at the relationship of the marketing function with the notion of the ‘artistic objective’. The definition above suggests there is a causal relationship between the intention of the artist; the product of the artist’s intention in the form of an artistic experience or artefact; and the benefits of it derived from the experience by the audience, customer or attender. In particular, it implies alignment between organizational and artistic objectives, or intentions. While this alignment exists in more mature artistic and cultural organizations, it may not be a view universally held by artists.

From the time of the Romantic Movement comes the notion of the artist as someone who stands outside ordinary society and normative organizational structures. In reaction to the Age of Enlightenment and increasing industrialization, the Romantics explored ideas of freedom, emotions, nature, and personal and political independence, all while pushing the limits of imagination. Subsequently, in the early decades of the 20th century, the avant-garde movement referred primarily to artists, authors, composers and philosophers whose work was opposed to mainstream cultural norms, often acting as a critique of society or political structures (Shukaitis & Figiel, 2014). In the early decades of the 21st century, the accessibility of new technologies enables individuals and communities to co-produce art in new and democratic ways; acting to a greater or lesser extent as artists themselves.

This kind of conceptualization of the artist positions them counter to notions of management, the latter being activities which seek to create order and consistency within organizations. This tension is explored by Ian Fillis, who suggests it creates a theory/practice divide for arts marketing which fails to be adequately addressed in marketing theory derived from business entities (Fillis, 2006). He suggests that it is difficult to separate the product of art from the artist as producer; and that it is difficult to understand the nature of arts products using concepts based on utilitarian or functional benefits. Finally, given the ways that artistic activity impacts on the ways we think, he questions the ways in which the artistic activity itself shapes and impacts on the marketing process, acting as a catalyst for creative change (Fillis, 2006).

In a postmodernist view of the artistic experience, arts marketers work as cultural intermediaries, acting as agents to constitute art and its meaning alongside other cultural participants, the artists and the consumers, and the art product itself (Meamber, 2014). The artist creates art, and arts experiences, from their own socio-cultural understandings refined by their individual creativity and imagination. Cultural intermediaries then try to ascribe meaning to the products of the artist, and artistic activity, as they market them. Audiences, or individual cultural consumers, can choose to accept or reject the meanings mediated to them through the process of marketing; and will themselves appropriate artistic experiences to establish their own meanings as part of their shaping of their individual identity. So the process of artistic experience is iterative, with arts marketers being an essential actor in the development of meaning (Meamber, 2014). The implications of this, for arts marketing staff, is to frame arts marketing as an essentially moral activity, closely allied to the value of the arts as an activity (O’Sullivan, 2014). Later in this chapter, we will look further both at notions around value in relation to arts activity; and at concomitant ethical issues for arts marketing practitioners. First, however, we need to consider further influences on the arts environment beyond arts organizations, individual artists and consumers of arts experiences.

Cultural policy and arts marketing

On a national level, most political administrations value the arts as something worth promoting. They are seen as what economists call a ‘merit good’ – in other words, something of social value (like preventive healthcare and education) but which people might not be prepared to pay for, if left to themselves. As a result, governments tend to see supporting the arts as part of their remit (although the priority given to this is variable). For some governments, arts policy is framed as part of their wider take on culture. As such, policy for the arts will be determined by the relevant state department. In other countries, some distance between the state and the producers is seen as essential to free speech and democracy so there will be an ‘arm’s-length’ arrangement, designed to demonstrate a separation between government and artistic expression. In other places, the state is more prepared to surrender control of the arts to the market, not seeing artistic activity as directly a function of government but, rather, as a decision for the individual. In reality, the truth in most places is rather more complex than any of these models suggest; and a mixed mode of state involvement in the arts and private activity exist side by side.

Box 1.2 What is cultural policy?

…culture may now be said to be the whole complex of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a society or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters, but also modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems, traditions and beliefs.

Source: UNESCO, 1982.

Box 1.3 Examples of national structures to support the arts and cultural activity

Australia Council for the Arts

Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture, Botswana

National Culture Fund, Bulgaria

CFLAC – China Federation of Literary and Arts Circles

Secretaria de Cultura de la Presidencia, El Salvador

Fiji Arts Council

Arts Council of Ireland – An Chomhairle Ealaíon

Creative New Zealand – Toi Aotearoa

Ministry of Culture and Information, Saudi Arabia

Statens Kulturråd – Swedish Arts Council

Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Vietnam.

Source: IFACCA members.

The policy objectives of different countries will change in line with national priorities; particular administrations in government; and local challenges, such as the rights of indigenous peoples. Arts activity may be more or less closely aligned to other national policies – economic, educational, healthcare or social mobility. Structures that support arts activity may also be concerned with the preservation of language, with issues of rural populations and with a concern for diversity. Large-scale national events like the Olympics can offer an opportunity to showcase a Cultural Olympiad, to broaden and extend the reach of the main event nationally and internationally.

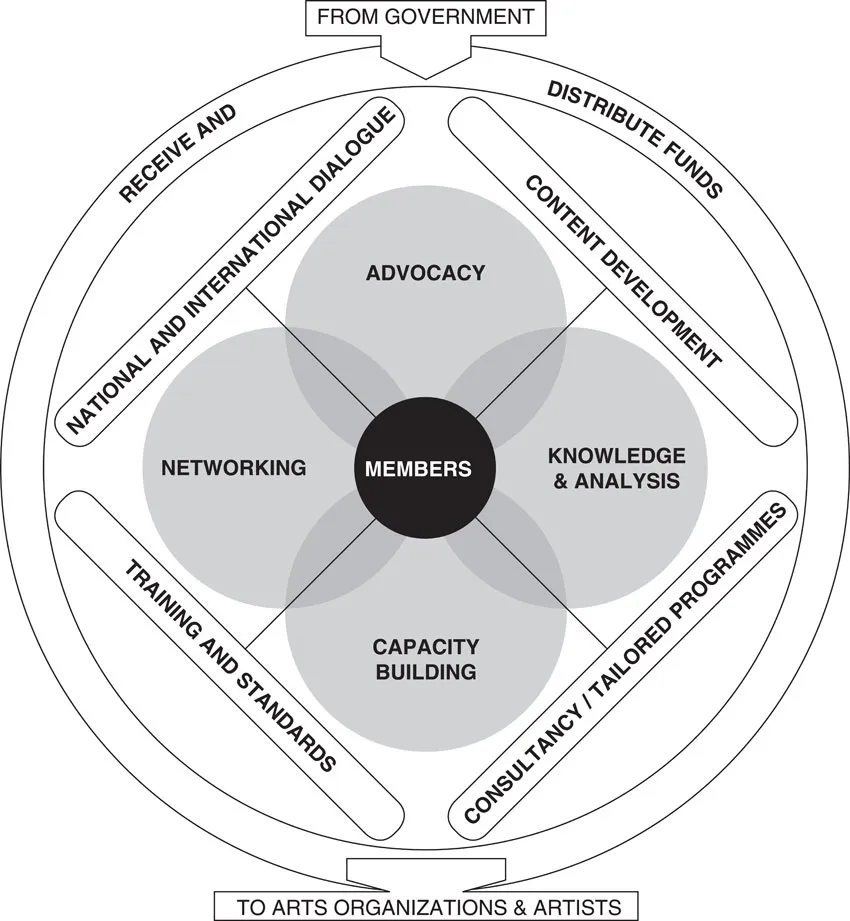

Since 2003, these many kinds of central policy-making bodies have been supported by the global organization, the International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA). It is headquartered in Australia, and promotes a vision of a world in which arts and culture thrive and are recognized by governments and peoples for their contribution to society. Its purpose is to support members to succeed and be a global voice advocating for the arts and culture. Its principal activities are displayed in Figure 1.1, and these activities could be construed as also characteristic of the main activities of IFACCA’s member organizations at a national level. In addition to these activities, many of the national bodies will also have a role in sourcing and distributing funds to artists and arts organizations.

Figure 1.1 The role of national arts bodies.

State support for the arts

In the UK and much of Europe, such state support is through direct funding mediated selectively through a mixture of national and local agencies and local, or regional, authorities. In the USA, the emphasis is on forgoing tax revenues to encourage private and corporate giving to the arts by offering tax incentives to donors. The USA was relatively late in adopting public funding support for the arts, with the foundation of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) not happening until 1965. The NEA claimed a remit towards ‘high art’ through supporting excellence, rather than the more pluralist and innovative approaches that tended to co-exist alongside established art forms at that time in Europe. Such different forms of support around the globe make like-with-like comparisons between nations very difficult. While politicians tend to agree that the arts are a good thing, the question of subsidizing them remains controversial (a subject to which we will return in the next section). Interestingly, all political parties debate the issue with equal ferocity, and find little consensus within party ranks. Alongside the ‘merit good’ argument are cases made on philosophical, aesthetic and economic grounds. These ideas, however, remain contested, with definitional difficulties about what constitutes value in the arts. Even when an accounting perspective is taken of the notion of value, equating classic accounting principles to artistic products is problematic. This, as we have seen above, relates at least in part to the ways in which artistic experience is co-produced by the author or creator of the activity, consumers of the activity, and cultural intermediaries, interacting with the artistic product in an iterative dialectic.

What is the value of the arts?

Principles of artistic value clash with commercial cost-revenue principles (Hutter, 2015). From the perspective of the consumer, the experience of the artistic event (whether it is reading a book, looking at a picture or attending a show) can create disappointment or pleasure, which response may incorporate the participation of the consumer in observing the experiences of others and co-creating judgements on the value of the experience (Hutter, 2015). So the value of an artistic experience can vary markedly even for an individual, as consumers can change their perceptions, maybe through revisiting the artistic product or through reflecting on the value attributed to it by others. This needs to be borne in mind when thinking about what constitutes quality in the arts, particularly perhaps when defending the case of activity currently viewed as having a low value.

From a national policy perspective, the arts and cultural industries are seen as having significant economic force, both directly in terms of numbers employed and contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) and indirectly, through fostering a capacity for creativity and innovation in the workforce. A focus on the economics of the cultural industries sector is sometimes attributed to Richard Caves, a Professor of Economics at Harvard in the USA (Caves, 2000). However, various national governments have attempted to quantify the value of the arts to the economy over an extended period of time, with greater or less success. More latterly, this activity has been supported by UNESCO. In the second of their major reports into the global scope of the creative industries (UNESCO, 2010), they estimate it is worth $592 billion. More telling, the developing countries’ share of this amounts to some $176 billion, 43 per cent share of the total global creative industries sector; a contribution growing at a rate of 13.5 per cent per annum in the first decade of the century. The dynamism of this growth does suggest that the creative industries are a powe...