![]()

Part I

The Universalizing System: Militarized Corporate Capitalism and the Apocalypse

![]()

1

The System and Its Discontents: The Militarized Matrix versus Us

“What the main drift of the twentieth century has revealed is that the economy has become concentrated and incorporated in the great hierarchies, the military has become enlarged and decisive to the shape of the entire economic structure; and moreover the economic and the military have become structurally and deeply interrelated, as the economy has become a seemingly permanent war economy; and military men and policies have increasingly penetrated the corporate economy.”

C. Wright Mills, 1957

“This country has socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for everyone else.”

Martin Luther King

“The prisoners of the system will continue to rebel, as before . . . The new fact of our era is the chance that they may be joined by the guards. We readers and writers of books have been, for the most part, among the guards.”

Howard Zinn

Defining the System

America’s second richest man, Warren Buffett, is becoming an unexpected multi-billionaire populist, saying famously that it’s outrageous that his secretary pays a higher tax rate than he does: “My friends and I have been coddled long enough by a billionaire-friendly Congress.”1

The majority of Americans seem to agree with the oracle from Omaha, telling pollsters for years that something is deeply awry in the United States: that the nation is moving in the wrong direction, that big money is trumping democracy, that inequalities of class, race, and gender are mushrooming while bigotry, xenophobia, violence, and social decay are spiraling out of control. According to progressive movement archivist, Paul Hawken, there are now “tens of millions of people working toward restoration and social justice.”2 Millions of other right-wing activists oppose Hawken’s left-leaning activists, but share a hatred of “the Establishment” or what their hero, Donald Trump, called “a rigged system.”

What many have not fully grasped is the depth of the systemic crisis and why popular malaise against “the system” is destined to grow. The 99%, whether on Right or Left, are mad as hell and not ready to take it anymore. In 2016, some of the same voters supporting Donald Trump also supported Bernie Sanders. After Trump’s election, Left and labor movements such as Fight for $15—to raise the minimum wage to $15—waged massive new protests aimed at building alliances with working-class Trump voters. Resistance to the Establishment is spreading and potentially uniting very strange bedfellows.

Camille Paglia, the literary critic, asks “Are we like late Rome, infatuated with past glories, ruled by a complacent, greedy elite, and hopelessly powerless to respond to changing conditions?”3 Well, yes to the Rome example, but no to the hopelessly powerless! While it enshrines democratic procedures such as voting, the system has long been run of, by, and for an oligarchic “power elite” of political leaders, military commanders, and corporate executives. Sociologist C. Wright Mills documented this more than half a century ago in his masterpiece, The Power Elite. The system wraps itself around ideals of democracy, but it undermines rule by ordinary citizens who dimly sense that corporations are the real “people” in power.

The system incorporates important forms of progress, rights, and creature comforts that help to sustain it even through deep destabilizing crises. To dismiss the technological, material, social, and political advances of capitalism— which Karl Marx himself celebrated as major progress beyond the feudal order it replaced—would be foolhardy. Yet the system prioritizes profit over people; as Marx wrote, capitalism “has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, callous ‘cash payment’.”4 Pope Francis writes that “In this system, which tends to devour everything which stands in the way of increased profits, whatever is fragile, like the environment, is defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which become the only rule.”5

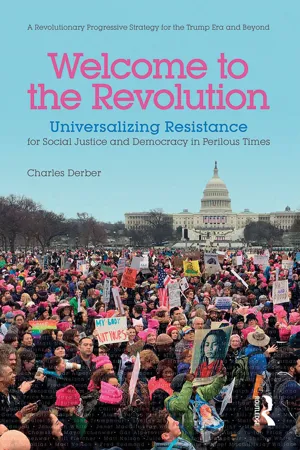

Occupy Wall Street movement protest, New York City © Michael Rubin/Dreamstime.com

The Establishment running this system is losing public faith as it breeds ever more crises and inequalities. This opens entirely new horizons for universalizing movements. But the global corporate system—while facing antiestablishment activism and now contending with the uncertainties and dangers of its rogue populist President, Donald Trump—remains the governing system.

That is why we must shine a bright spotlight on the system, even as it simultaneously universalizes and begins to unravel, confronted by universalizing movements from Left and Right hoping to build a revolutionary new order.

Intersectionality: How Race, Class, and Gender Hierarchies Make Up the System and Shape the Activist Agenda

Militarized capitalism is what social scientists now call an “intersectional” system. Intersectionality is what makes universalized resistance both necessary and possible.

Black feminist scholars, including Patricia Hill Collins, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks introduced the idea of intersectionality to help explain the relations between class, race, and gender. All structures of power are intertwined in what Collins calls “a matrix of dominations,”6 and constitute pillars of the larger system of militarized capitalism. Each pillar, an anti-social form of power, has its own roots, some preceding the contemporary system. But all are partially caused and intensified by the system, and are integral to it—and all create intertwined oppressions that must together be overcome in a new order. As writer and intersectional activist, Shiri Eisner, puts it, “It means understanding that different kinds of oppression are interlinked, and that one can’t liberate only one group without the others,”7 an insight at the heart of universalizing resistance.

Movements today are increasingly recognizing the intersectional nature of the system. Alicia Garza, a founding activist of Black Lives Matter, says

[W]e’ve been having a lot of conversations about state violence against Black domestic workers . . . People say “what’s the connection?” Well, we are three dimensional beings and black women who are working in other people’s homes have families and are afraid for their children. These are women who are living in communities that have really high levels of unemployment . . . over sixty percent of black domestic workers that we talked to said that they didn’t have food in the last month.8

Garza is making clear that Black Lives Matter sees police violence against Blacks as part of a much bigger systemic issue intertwining race, class, plutocratic economics, and survival.

Garza, a democratic socialist, is explicit about the need to challenge capitalism to end racism:

[W]e are living in a political moment where for the first time in a long time we are talking about alternatives to capitalism. . . . It is a political moment that’s opening opportunities to envision a world where people can actually live in dignity. So whether that’s abolishing a criminal justice that feeds off the labor and the lives of black and brown people, whether that’s abolishing an economic system that thrives on exploitation, poverty and misery: this is the time for us to not just dream about what could be, but also start to build alternatives that we want to see.9

This is a manifesto for resistance against an intersectional system, where Black Lives Matter is connecting the dots and recognizing the threat to individual and collective survival, while envisaging a revolutionary new system.

Despite its democratic ideals, the system is a structure rooted in intersecting caste and class hierarchies, as well as militarism and violence toward the environment, thus melding economic (class) and caste (race, gender, sexual orientation) power and inequalities. Caste refers to statuses in which people are born and which they cannot change: caste systems are based on “blood” or “essence,” whether perceived as God-given or built into one’s genes. Aristocratic noble “blood” or serf inferior “essence” were central in the polarized castes of the Middle Ages. We think of caste systems surviving today in faraway countries like India, where Brahmins have been seen as an innately superior group and the “Untouchables” so inferior that they should not ever be touched or given rights.

But many modern societies, including that of the United States, have their own caste groups, including those based on gender, skin color, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. The American system claims to overcome caste as a basis of social discrimination, but it never did (except in legal form); it involves a profit-driven system based on inequalities of capital, divisions of wealth ownership, and race and gender hierarchies wrapped tightly around each other like so many intersecting strands of system DNA.

Intersectionality is in the DNA of capitalism—and as the system universalizes, we desperately need a new intersectional resistance in the United States and the world, that can build a new democratic order free of classism, sexism, and racism. Sadly, this new resistance, while beginning to surface and grow, remains maddeningly elusive, with class movements torn asunder from race and gender movements, as well as from anti-war and environmental struggles. The only antidote: new rainbows of resistance uniting classes, castes, colors, and causes around the world in the ultimate service of a revolutionary project of democracy, social justice, and survival. As the feminist poet, Audre Lorde, writes, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because there is no such thing as a single-issue life.”10

Activists increasingly recognize the “intersectionality” of the system. NTanya Lee and Steve Williams, brilliant and seasoned activists themselves who interviewed 157 activists in 2011 and 2012, report that their interviewees

offered a sharp intersectional analysis of the issues that they are working on. Teachers are grappling with climate change; domestic workers are taking on immigration reform; unemployed people are confronting banks; transgenders are talking about the need for healthy and sustainable food choices; and the organizations in each of these sectors are struggling to connect the dots.11

At the same time, intersectional theorists recognize that some issues sometimes must take personal precedence, as in this story from the great African-American writer, bell hooks:

I was teasing my brother that he was penniless, homeless, jobless. Right now in his life, racism isn’t the central highlighting force: it’s the world of work and economics. It doesn’t mean that he isn’t influenced by racism, but when he wakes up in the morning the thing that’s driving his world is really issues of class, economics and power as they articulate themselves.12

The system has defined itself from its late Medieval origins as “beyond caste.” The existing system is, in fact, an order that moves toward eliminating legal privileges based on race and gender or other inherited caste identities, a very important form of progress. There are now African-American, Hispanic, and female leaders in every field, as well as middle classes comprised of women and people of color. Nonetheless, the system, which has never truly acknowledged the role of race in forming and sustaining the capitalism system, makes certain racial legal and social reforms while deepening the economic exploitation of both poor African-American and white working-class groups.

As Cornel West has noted, racial domination, while totally intertwined with economic injustice, is not “identical” to it; race and gender exploitation are not simply residuals of economic income or class. Racism and sexism existed long before capitalism. West writes that

Cultural practices, including racist discourses and actions, have multiple power functions (such as domination over non-Europeans) that are neither reducible to nor intelligible in terms of class exploitation alone. In short these practices have a reality of their own and cannot simply be reduced to an economic base.13

But racism has always been central to keeping white workers bonded emotionally with their corporate bosses and sustaining capitalism. White supremacy, long a central feature of US Southern culture, is also a disguised prop of capitalism throughout America; it gives white workers the feelings of respect, belonging, and superiority in a system that increasingly impoverishes them. Donald Trump’s America First politics is part of what Samuel Huntington might call a “civilizational war” against people of color, while also offering poor “white trash” and declining working-class whites a reason to identify with Trump’s billionaire-run capitalism. President Trump campaigned and won as a civilizational as well as class warrior, as a dog-whistle white nationalist as well as a capitalist profiteer.

Racism is intimately tied to class exploitation. Even in the wake of a Black President and cracking of the glass ceiling for women, militarized capitalism cannot operate without racism and sexism. Wealth gaps between Black and white families exploded under a Black President. It is still the case that two-thirds of those in poverty are female.

“Leaning in” to the system, as Sheryl Sandberg, a top corporate executive at Facebook describes it in her best-selling book, can pay off for privileged female managers like Sandberg.14 But what about poor and working women? Their “leaning in” leads to persistent insecurity and failed dreams, as they compare their fate with Sandberg’s. Working-class women voted for Trump in 2016 rather than Hillary Clinton, signaling that economic populism has to be part of feminism. Sandberg illustrates a “silo” feminism that hurts women by ignoring the very different realities of affluent white females, white working-class women, and minority women of color. Ms Sandberg: stop ignoring the class realities of the corporate system that pays you so well!

In fact, it is to be hoped that Sandberg listened to the hundreds of thousands of women who flocked the streets the day after Trump’s inauguration. Leaders such as Senator Kamala Harris of California, when asked about the women’s issues at stake, talked immediately about economic inequality, jobs, social welfare, racism, and climate change; these are all, she made clear, “women’s issues.” That historical Women’s March opening the Trump era made clear that feminism was no longer just about justice for women, but for all people. The Women’s March opened a new feminist wave that is militantly intersectional: that does not separate women’s rights from the rights of all people and all species.

And so too must be a new wave of anti-racist movements, as shown by Black Lives Matter and the thought of people such as Michelle Alexander and Alicia Garza. The slave trade and slavery itself were a rich source of profit in early Western and American capitalism. We have eliminated the legal basis of slavery, but not the profitability of institutional racism and sexism. On top of such economic violence is police violence against African Americans and a war against Hispanic immigrants that is applauded by many white male workers (and some female workers too)—those who love Donald Trump, or other Republicans. The system helps these workers identify with the corporate system that bends in their racial favor and turns them against African-American workers, even as it undermines their wages and job security and threatens their survival. African-American socialist and labor leader, Bill Fletcher, J...