- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Assessing Children's Learning (Classic Edition)

About this book

"It is my sincere wish that the teachers of those thousands of children, who increasingly are also teacher educators, read and learn from Assessing Children's Learning. The hope is that they will go on to make a reality of theimaginary but not impossible classroom and make moral judgements and choices in the best interests of children." - Sue Sw

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Learning from Jason

In February 1985, a class of seven- and eight-year-olds, in their first year of junior schooling, were taken into the school hall where they sat at individual tables to take a mathematics test (NFER 1984). The headteacher read out the questions, and the pupils wrote the answers in their individual test booklets. One of those children was Jason, aged seven years, six months, who had spent two and a half years in the infant department. There are 36 questions in the test and Jason answered them all. One of the answers was correct, giving Jason a raw score of two, and a standardised score of 81, a ‘moderately low score’, according to the teacher’s guide to the test.

A teacher in Jason’s school showed me his test booklet, and I date my interest in assessment from that day. In the analysis of Jason’s test performance that follows, we will be able to see some obvious inadequacies in the use of formal group testing as a way of assessing individual children’s learning. But I will also argue that the test booklet does tell us some very important things about Jason’s learning, and about other children’s learning, that must be taken into account in a full understanding of the process of assessment.

Jason’s test responses show us, first of all, what he has failed to learn about mathematics. More significantly, they give us an indication of the gap that yawns between what his teachers have taught him and what he has learned. In other words, the test booklet forces us to look critically at the relationship between teaching and learning. Furthermore, Jason’s case-study invites us to explore the interplay of the rights and responsibilities of teachers and learners.

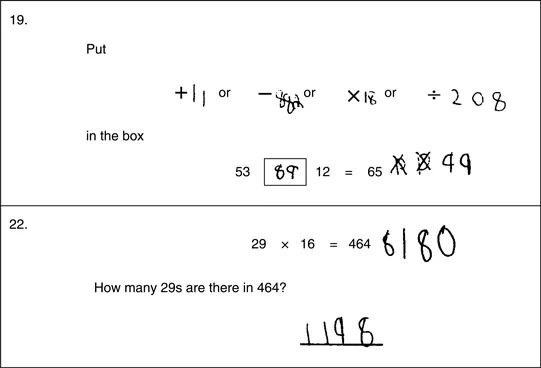

But first, what has Jason learned during his eight terms in school? He has learned how to take a test. His answers are written neatly, with the sharpest of pencils. When he reverses a digit and sees his mistake, he crosses it out tidily. He places his answers on the line or in the box as instructed, though he often adds some more digits in other empty spaces, as if he interpreted a space as an invitation to write. (See questions 19 and 22 in figure 1.1.) He has learned to copy numbers and letters neatly and accurately, even though this is not what is being asked of him. (See questions 5 and 6 shown in figure 1.2.)

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

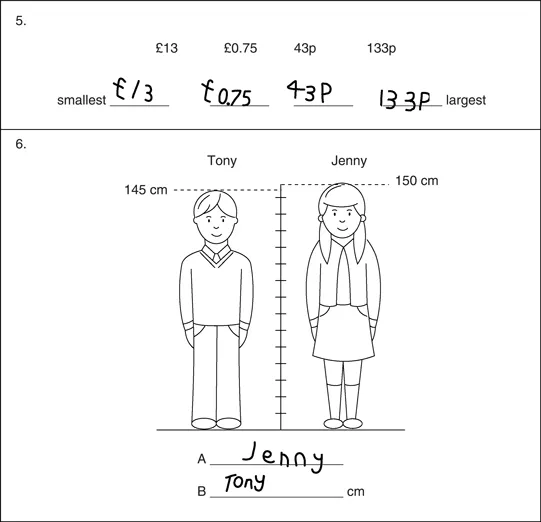

In question 5, Jason has been asked to rank the four amounts of money in order, from the smallest to the largest. In question 6, he has been asked (A) who is the shorter of the two children, and (B) by how many centimetres. Jason has simply copied the print from the question into the space provided for the answer.

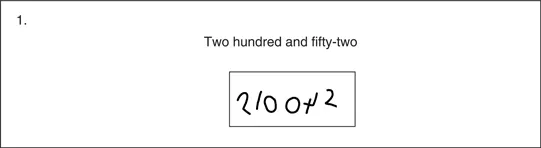

He has learned to listen and to follow instructions carefully, as closely as he can, though his short-term memory does sometimes let him down. In question 1, for example, he was asked to write in numerals the number two hundred and fifty-two. As we can see, (figure 1.3), he has almost done so, writing two, a hundred, and forty-two. He has learned to stay with a task and complete it. Other pupils in the same class answered only a few of the test questions, leaving many items blank. Others scrawled and smudged their responses: Jason’s presentation is exemplary.

Figure 1.3

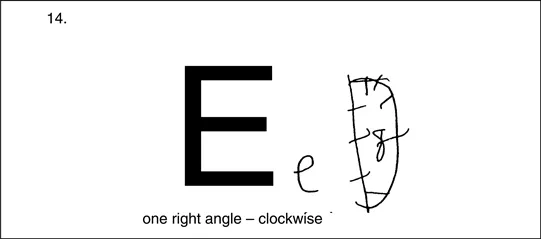

He has not, it is apparent, learned very much mathematics. He has learned that in a mathematics test, he is required to write numbers, which he does, with one exception. (See question 14 in figure 1.11.)

Figure 1.11

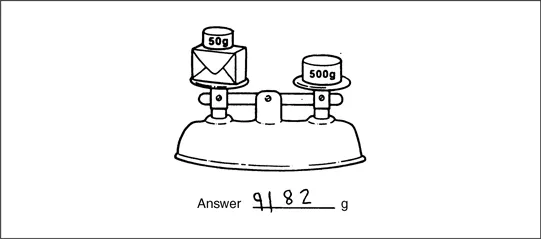

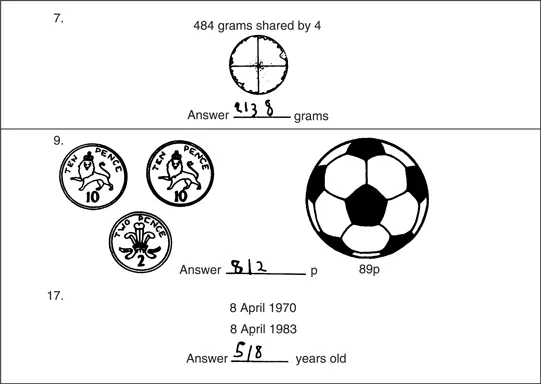

There is no evidence that he has learned the value of the numbers that he writes. So, for example, in question 4, he is asked to calculate the weight of the parcel on the left, if the scales balance (figure 1.4). He has responded by writing four digits in the space provided. I am certain that he has not calculated – or miscalculated – that 9182g + 50g = 500g, or that 500g – 50g = 9182g. He has simply written some numbers in the appropriate place for an answer. He uses the same approach in question 7, question 9, and question 17 (figure 1.5).

Figure 1.4

Figure 1.5

Question 7 is a simple division problem; question 9 asks how much more money is needed to buy the football, and in question 17, the pupils are required to give the age of a child born on 8 April 1970 on 8 April 1983. Another child in Jason’s class interpreted this question as a subtraction problem; working from left to right he seems to have thought to himself: ‘8 from 8 is 0, put down 0); April from April is 0, put down 0; 1983 from 1970’ – here the answer trails away as the pupil realises he cannot complete the problem.

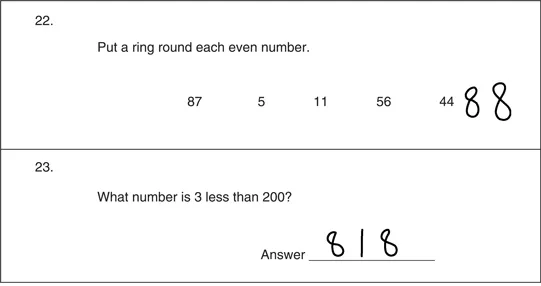

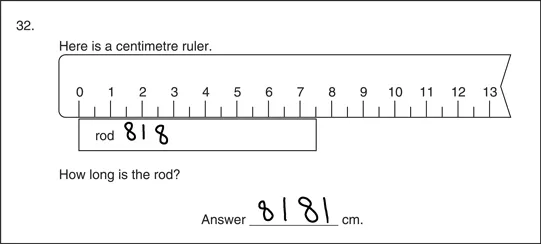

Jason frequently writes the number 8, and it is tempting to speculate about the reason for this. (See questions 22, 23 for example in figure 1.6.) Is it a satisfying number for him to write? Has he recently mastered the art of forming it with a single stroke? Or is it possible that he has noticed the front cover of his test booklet (figure 1.7), and that he has seized on this bold and impressive numeral as a possible clue to what is being asked of him?

Figure 1.6

Figure 1.7

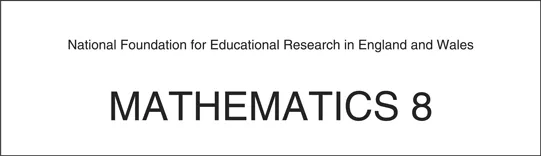

He uses the same configurations of numbers several times, suggesting that he is not attending to or discriminating between the meaning of the context of the different questions (figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8

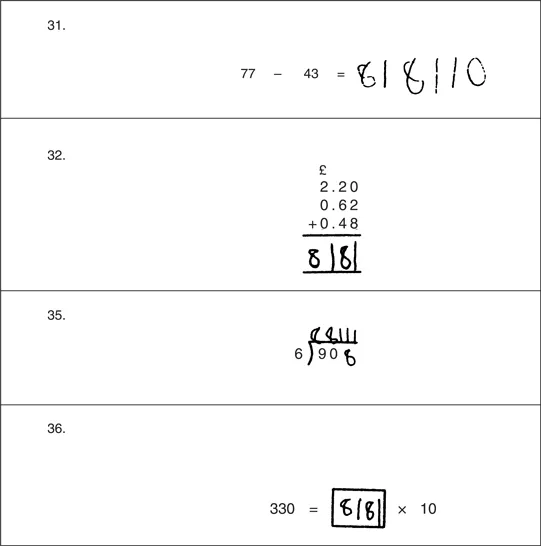

But sometimes, it seems, there may be other reasons for his responses; in question 28, for example. It seems just possible here that Jason has read off the length of the rod on the ruler as nearly 8, and interpreted the half-centimetre mark on the ruler as figure 1. How long is the rod? It could be that Jason said to himself ‘8, and back a bit to this 1 here. 8. Eight. One.’ Why has he written it twice? To fill this allocated space?

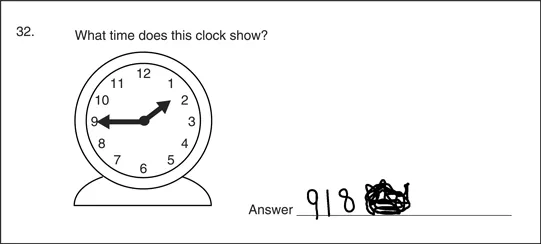

More convincing evidence that Jason attends to at least part of the content of the question, as he sees it (not as the tester sees it), can be seen in question 34 (figure 1.10). What time does this clock show? Did Jason reflect ‘There is the 9,there is the 1; perhaps an 8 for good measure …’? It is at least a possibility.

Figure 1.9

Figure 1.10

Question 14 is more complex. The instruction is: Draw this shape as it will look when it has been rotated one right-angle clockwise. Here I believe Jason makes his first real error, and writes a letter (lower case ‘e’) before remembering that this is a mathematics test. It is not, at any rate, an impossible or improbable interpretation of what he has done – he will, after all, have seen the capital and lower case letters presented together in just this way in many contexts during his school career. The rest of his response is more interesting; I suggest that Jason heard the word ‘clock’ as a significant instruction and, remembering previous class-work on clocks, responded with a sketch of a clock, on which he then duly marked the 8.

In these last two examples, I believe there is substantial evidence that, against what must be, for him, inconceivable odds, Jason is struggling to make sense of the test, and what his headteacher is asking him to do. His mathematical understanding is still too scanty to be of much use to him, but he uses all the other clues he can get. This is, I think, a remarkable achievement, and a tribute to Jason’s persistence, to his longing for meaning.

It is also possible to recognise Jason’s self-restraint, and his passivity, during what was presumably an uncomfortable experience. He cannot have been feeling relaxed, confident, sure of himself and certain of success, during the test. Or does he not even know what it is he does not know? It seems more reasonable to assume that he does know, very well, that mathematics, and the mathematical tasks his teacher gives him, make no kind of sense at all. And yet he is prepared to sit and comply, as far as he is able, with a string of incomprehensible instructions.

Jason may not have learned much mathematics but he has learned some important rules about being a pupil. Mary Willes’ study (1983) of children entering a reception class charts the inexorable process by which children – spontaneous, curious, independent – are transformed into pupils, who know the rules. Her pessimistic summary of the task of the pupil seems to describe Jason’s condition all too accurately:

… finding out what the teacher wants, and doing it, constitute the primary duty of a pupil.

Willes (1983) p.138

Jason has learned not to resist and rebel when his teachers ask him to do the impossible. Throughout the test he sat at his desk and did as he was told, as far as he was able. It is only in my fantasy that Jason overturns his desk and hurls it at his headteacher, screaming defiance, demanding his rights as a pupil, as a child, as a human being.

When I was first shown Jason’s test booklet, the emotional impact on me was very strong. As a result, it has taken me some time to see beneath the surface features of this piece of primary practice to the larger, more abstract issues it exemplifies. Jason’s test performance does certainly illustrate inevitable weaknesses in formal group testing, in particular the way in which such tests cannot tell us anything about the processes of pupils’ thinking, but only whether pupils arrive at the unique right answer. But there is more to be said. In Jason we see a child who, like all other children, is capable of learning. He has been learning, during his three years in school, but much of it is not what his teachers intended. We have little evidence from this test of his learning in the cognitive domain, but we can see how much he has learned about the social conventions of the school – how to keep his pencil sharp, how to stay in his seat, how to take a test, how to be a pupil. In the affective domain, we can see how Jason has learned not to express dissatisfaction or disquiet when meaningless demands are made on him. And yet we can also see signs – small perhaps, but significant – that, in the limited ways left open to him, Jason is still struggling to make sense of what goes on around him in the puzzling world of school.

None of this has come about on purpose; his teachers have not maliciously plotted to keep Jason in the dark, to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- 1. Learning from Jason

- 2. Looking at learning: introductory

- 3. Looking at learning: what is there to see?

- 4. Looking at learning: learning to see

- 5. Ways of seeing: trying to understand

- 6. Understanding ourselves

- 7. Trying to understand: making it work

- 8. Practices and principles

- 9. Rights, responsibilities and power

- Conclusion

- Afterword to the second edition

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Assessing Children's Learning (Classic Edition) by Mary Jane Drummond in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildung Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.