eBook - ePub

Teaching Introduction to Theatrical Design

A Process Based Syllabus in Costumes, Scenery, and Lighting

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Introduction to Theatrical Design

A Process Based Syllabus in Costumes, Scenery, and Lighting

About this book

Teaching Introduction to Theatrical Design is a week-by-week guide that helps instructors who are new to teaching design, teaching outside of their fields of expertise, or looking for better ways to integrate and encourage non-designers in the design classroom. This book provides a syllabus to teach foundational theatrical design by illustrating process and application of the principals of design in costumes, sets, lights, and sound.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Teaching Introduction to Theatrical Design by Eric Appleton,Tracey Lyons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section III

Lighting Design

Chapter 11

Week 11

“The fundamental lighting of a production is outlined by the playwright’s manuscript. The indications of place and time of day, demanding specific details such as lamp-light, sunlight, moonlight, etc. (which are called motivating sources) are unconsciously or consciously dictated by the playwright.”1

Stanley McCandless, A Method of Lighting the Stage

The framing topics for this week are:

- Research

- Observation and Analysis of Light in Images

- Design Mechanics

- Stage Lighting Vocabulary

- The Functions of Light

- The Controllable Properties of Light

- The Standard Angles of Light

Instructor Supplies Needed

- Photos/images for observation and analysis

- Standard Angles of Light handout

- Camera to photograph scenic models

- Light lab materials:

- Figure (doll)

- Four to six moveable lighting units

- Way to control intensity of individual lighting units

- Black background

- White background

- Objects to place in background of light lab

Our Approach to Lighting Design

We focus on naturalistic, motivated lighting as the foundation of meaningful theatrical light. One reason is because motivated lighting can be demonstrated by doing something as simple as turning the room’s overhead fluorescent lights on and off. The concept of naturalistic, motivated light is one that’s easy for students to grasp: e.g., a scene taking place in a yard on a sunny day is lit by the sun. Once that source of light is acknowledged, the complexity then lies in creating the appropriate sunlight with available lighting equipment.

Depending on the style of the production, of course, the role of lighting can vary greatly and naturalism may not always be a goal of the designer. In some cases light becomes a more abstract tool as in dance, where the dimensional revelation of the dancer’s body is a primary concern and there is often no expectation of knowing what ‘real’ source (like the sun) is emitting the light. For rock concerts, spectacle created by the shape and movement of beams of light through haze is a major visual element, and in many cases replaces physical scenery. A production attempting to recreate the look of an eighteenth-century drama may go so far as to replicate the footlight-driven illumination of the period. However, even these applications of light can be discussed and planned using the steps and language introduced in the following chapters.

Lighting design and technology use a lot of jargon which is very difficult to avoid. As terms are introduced to the class, be sure to define them, use them consistently, and review them as often as possible. The vocabulary boxes included in this chapter are less memorization lists for the students than to help the instructor provide a definition when the need arises.

Book Recommendation

If you are new to and a bit frightened by stage lighting, David Hays’ Light on the Subject: Stage Lighting for Directors and Actors – and the Rest of Us is a pleasant, short, yet thorough introduction. Full of anecdotes and gentle instruction, Hayes leads the reader through then-current equipment into conceptual tools and the working relationships between the lighting designer and other members of the production team. “Stage lighting is not a black art. It can be practiced openly.”2

Lighting Vocabulary Terms

Motivated light on the stage that appears to come from an identifiable source such as a sconce, chandelier, window, or the sun

Light, Unit, Fixture, Luminaire generally interchangeable terms that refer to the piece of theatrical stage equipment that emits light

Dimmer the piece of equipment which controls how much electricity is sent out to an incandescent unit, and therefore determines how bright is the light that is emitted

Console or light board, also called a desk; the piece of equipment that tells the dimmers how much electricity (or data) to send to the units

LED Light Emitting Diode; electronic light source that is fast replacing incandescent light sources due to color changing capability and reduced energy usage. Requires a high degree of electronic control

Incandescent Light source with a filament enclosed in a glass bulb; light is produced by the wire’s resistance to the electricity sent through it

Conventional A lighting unit that uses an incandescent light source and has no in-built motorized movement

Lamp Non-theatre people call this a lightbulb

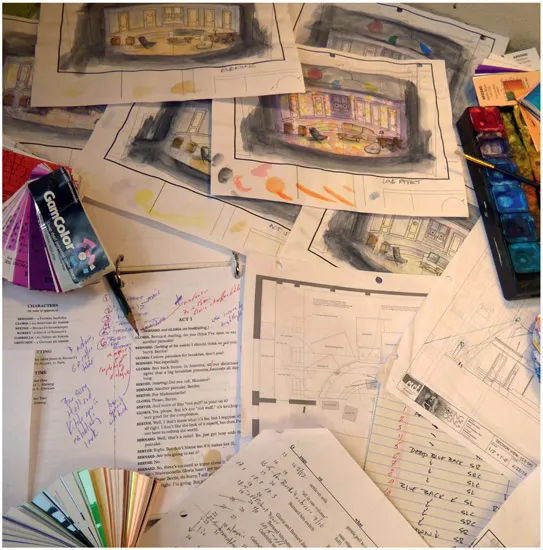

Light Plot A drawing that shows where each and every lighting unit is to be placed in the venue

Technology plays an intimate role in lighting design and some textbooks feel that it is useful to introduce the arcana of equipment first – lay out the tools, then learn how best to use them. In our class, the first concern is to decide what the lighting should look like, and then worry about equipment. Learning the difference between communication tools (such as a storyboard), and execution tools (such as a light plot) is critical. Some student lighting designers conflate the completed light plot with the completed design, forgetting that the light plot is a drawing that is only one step (though admittedly a major step) in the implementation of the design. If, in a portfolio, a plot takes more precedence than photographs of the populated lit stage, it’s evidence that the student designer does not yet understand this. Storyboards and research images are not only essential phases of the design process but speak a language with which directors (and the other members of the design team) are familiar.

On the other hand, for scenery and costumes physical objects manifest the design. A costume is built in the shop and worn by the actor. While it can be argued that the costume does not ‘live’ while hanging on a garment rack, it can still be seen and touched. Lighting, however, does not make its way to the stage in the same way. When the equipment is turned off, there is no light. Looking at the lighting units hung around the venue does not give a viewer a sense of the light that will be seen during the play. Looking at the numbers displayed on a lighting console’s monitor does little to reveal the movement of light through time that will be experienced by the audience. This is one of the reasons the light plot becomes a stand-in for the lighting design as a whole; it’s a physical artifact condensing all of the designer’s thought about the show into a single technical drawing.

In an introductory class it remains necessary to not only talk about the light the designer intends to put on the stage, but how that light will eventually be put on the stage. This doesn’t mean in-depth discussion of equipment, but rather, discussing factors like angles, intensity, and direction. These factors are controllable properties of light that will, down the road, help a designer Figure out where the appropriate lighting units will be placed and how they will be controlled.

The chapters of this section will shuttle back and forth between these aspects of lighting design. The first session introduces several layers of vocabulary that will help the class discuss light more precisely. Later sessions will use script analysis and research to determine the desired light for a scene. Sketching will aid communication of those intentions. Finally, we’ll develop diagrams of how that light might be created in a theatrical venue. Along the way there will be frequent trips to the light lab to try it all out.

A light lab of some sort will be extremely useful. Whereas in the scenic section, the instructor could fold a piece of cardstock and instantly have a wall, to demonstrate stage lighting you need to have equipment that produces light. Trying to teach introductory lighting in the theatre itself tends to mean spending a lot of time running from catwalk to ladder to booth for even the simplest set-up. If you do not have the resources to set up a classroom light lab, use three flashlights and a doll to demonstrate the standard angles of light (later in this chapter) and bring in more images of both the natural world and realized stage lighting to analyze. When you get to the portions of Chapters 12 and 13 that spend time building a scene in the light lab, focus instead on the half of that extended exercise that diagrams the lighting on the chalkboard. Then use Chapter 16 to explore breaking the stage into areas of control and the development of the preliminary channel hook-up.

“I am constantly being asked, ‘What kind of spotlight do you need to give afternoon sunlight?’ and my ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Section I Costume Design

- Section II Scenic Design

- Section III Lighting Design

- Section IV Sound Design

- Appendix A Our Current Syllabus

- Appendix B Materials for Introduction to Design

- Appendix C Two Short Plays by Eric Appleton, Used for Design Exercises

- Appendix D Sample Cue Synopses

- Appendix E Standard Lighting Positions and Unit Numbering

- Appendix F Design Timelines

- Glossary

- Index