![]()

p.5

Part I

Breastfeeding in the wider context

![]()

p.6

Chapter 1

Breastfeeding in context

The impact of society on breastfeeding

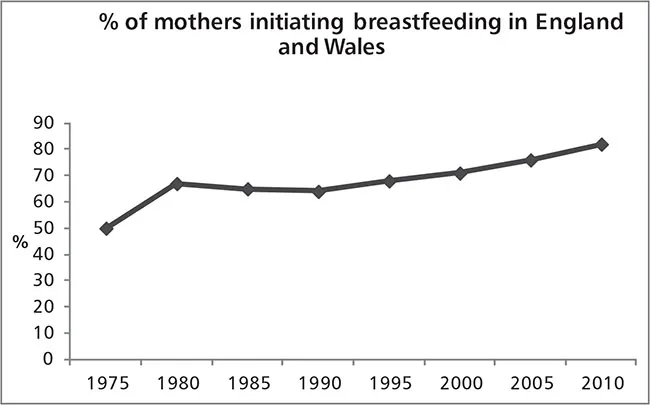

Society has a massive impact on breastfeeding – if we do not see breastfeeding but see only bottle feeding, the latter becomes normal. Breastfeeding reached a low point in 1975 with only 50% of women initiating breastfeeding (Foster et al. 1997). In that era, mothers were instructed to feed their babies no more frequently than every four hours and for a maximum of ten minutes on each side with frequent supplementation with formula milk. A certain way to set the mother up to ‘fail’ at breastfeeding. Since then the breastfeeding rate has slowly increased, with an initiation rate of 81% in 2010 (McAndrew et al. 2012). Exclusive, baby-led breastfeeding is now being encouraged (see Figure 1.1).

p.7

With most mothers now choosing to breastfeed at least initially, healthcare professionals need to consider how they can better protect, promote and support mothers in their chosen method of infant feeding. The intention of this book is not to make women who choose to bottle feed feel guilty or to imply that they don’t want the best for their babies, merely to support those who have chosen to breastfeed to do so for as long as they wish.

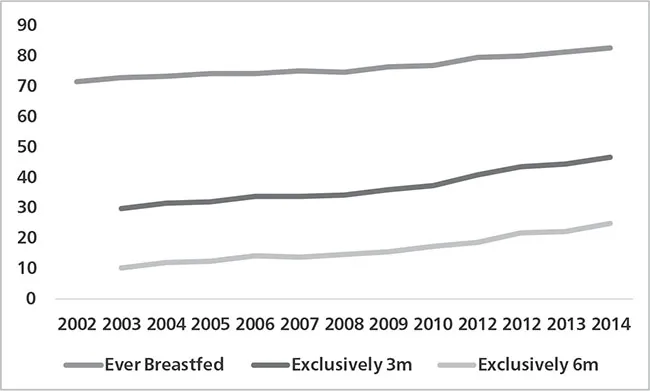

In the USA, the Healthy People 2020 objective is to increase the percentage of the population ever breastfed to 81.9% and those exclusively breastfed to six months to 25.5%. Data collected in the Breastfeeding Report Card 2016 showed that, nationally, 81.1% of babies were breastfed at delivery, 51.8% received some breastmilk at six months and 22.3% were exclusively breastfed. It is interesting to note that 17.1% of breastfed babies received some formula before they were 48 hours old (see Figure 1.2).

In Australia, 96% of babies were initially breastfed, 21% continued to receive some breastmilk at six months but only 15% continued exclusively. See Figure 1.3.

p.8

p.9

Health inequalities and the promotion of breastfeeding

Stuart Forsyth noted that breastfeeding is the only health intervention that can lead to better health outcomes for a child from the lowest socio-economic groups compared with an artificially fed counterpart from a more affluent family (Forsyth 2005).

In 1998 Sir Donald Acheson published the Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health report. He suggested that starting with maternal and child health will bring about the most rapid benefits in improving the health of society. This report drove the strategies to increase the initiation and prevalence of breastfeeding in the UK.

Maternal and Child Nutrition was published by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE PH11), which proposed to help improve the nutrition of pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and children in low-income households. NICE PH11 recommends that all healthcare professionals should have appropriate knowledge and skills to give advice on:

• the nutritional needs of pregnant women, including use of folic acid and vitamin D;

• promoting and supporting breastfeeding; and

• the nutritional needs of infants and young children.

There is also a recommendation on prescribing for breastfeeding mothers that will be discussed further in the Drug Reference section.

Obesity and infant feeding

The increasing number of children who are obese has become a major concern for the future health of the public in the UK and worldwide. The role of breastfeeding in reducing the risk of excess weight in later life was highlighted in the document Healthy Lives, Healthy People: A Call to Action on Obesity in England 2010.

Breastfeeding in public

The 2005 Infant Feeding Survey (McAndrew et al. 2012) noted that although women in the UK are now more likely to breastfeed in public, 47% reported difficulties in finding a place to breastfeed, 11% had been stopped or made to feel uncomfortable about breastfeeding in public and 8% had never attempted to feed in public. Interestingly, more than a third of bottle-feeding mothers said that they had never attempted to feed their baby away from home either. The Equality Act became law in England in 2010. It makes it clear that a woman cannot be discriminated against for breastfeeding her baby in public places such as cafes, shops and buses. For example, a bus driver could not ask a woman to get off the bus just because she is breastfeeding her baby.

p.10

Influences on breastfeeding initiation

Mothers from the lowest socio-economic groups, who are younger at the time of delivery and who have left full-time education at a younger age, are less likely to breastfeed than their socially more advantaged counterparts (McAndrew et al. 2012).

Influence of friends and family

Some women in the McFadden study (McFadden and Toole 2006) said that even family and friends found it ‘repulsive’ to be in the same room when they were breastfeeding and that grandparents, more than fathers, felt excluded if they had no opportunity to feed the baby. It was apparent that the opinion of family and friends was a stronger influence than that of health practitioners’ input on the advantages of breastfeeding.

Of mothers who were bottle fed themselves as babies, 63% were breastfeeding at four weeks compared with 85% of mothers who were entirely breastfed as babies. Mothers generally follow the example set by their own mothers. Similarly, for those mothers whose friends entirely formula fed their children, 49% were still breastfeeding at four weeks compared with 84% whose friends entirely breastfed their babies (McAndrew et al. 2012). We are more likely to follow the example of our peers to fit into the group. The influences on the breastfeeding mother can be plotted on a genogram to pro-actively identify potential barriers and negative influences (Darwent et al. 2016).

p.11

Impact of education on breastfeeding initiation

In a study (van Rossem et al. 2009) of 2,914 women, 95.5% of those educated to the highest level initiated breastfeeding while only 71.3% of those reaching the lowest educational level did. Educational level influenced breastfeeding experiences until the babies were 2 months of age, but not thereafter. The Infant Feeding Survey Results (Bolling et al. 2007, McAndrew et al. 2012) have repeatedly shown the same variation in breastfeeding initiation.

Peer support in populations where breastfeeding rates are historically low

Until breastfeeding is seen as normal it will remain difficult for mothers to initiate and sustain breastfeeding while they feel themselves to be acting in a manner that is not common or acceptable within their local society. To influence those mothers, an alternative means of support is required. One of these methods is the introduction of peer support workers. These are mothers who have breastfed and have undertaken additional training to work with other mothers in their neighbourhood. Their support has been shown to help initiation and prevalence in any area (NICE PH11).

p.12

Difficulties experienced with breastfeeding

Many women and healthcare professionals perceive breastfeeding to be difficult, painful, messy, restrictive and tiring. Why is there disparity between the importance and the practicality of breastfeeding?

Of mothers who initiated breastfeeding, the most common reasons for stopping in the first week were:

• baby not sucking/rejecting the breast (33%);

• having painful breasts or nipples (22%);

• mother feeling she had insufficient milk (17%);

• breastfeeding was inconvenient or that formula was more convenient (11%);

• breastfeeding took too long/was tiring (5%).

These mothers fulfilled the expectations that, despite their original commitment to breastfeeding, they had found it to be difficult.

However, if we look at how many women would have liked to have fed longer compared with those who have breastfed for as long as they wished, very few would probably describe themselves as ‘succeeding’ in breastfeeding – with 85% who gave up in the first two weeks saying that they would have like to breastfeed for longer. If we could ensure that all mothers who choose to breastfeed their infants could continue to do so for as long as they wish, the negative picture of breastfeeding might be addressed.

p.13

The purpose of this book is to reduce the number of mothers told to stop breastfeeding because of their need for medication and to add to the knowledge of why breastfeeding may falter and how it can be better supported and therefore maintained.

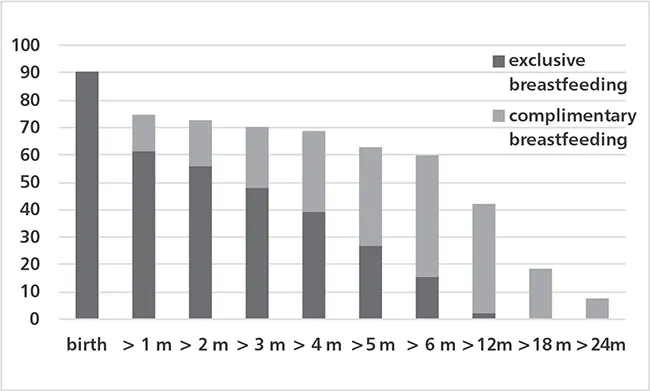

Exclusive breastfeeding rates

The definition of exclusive breastfeeding is that an infant receives ‘only breast milk, and no other liquids or solids, apart from medicine, vitamins, or mineral supplements’. Guidelines recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months.

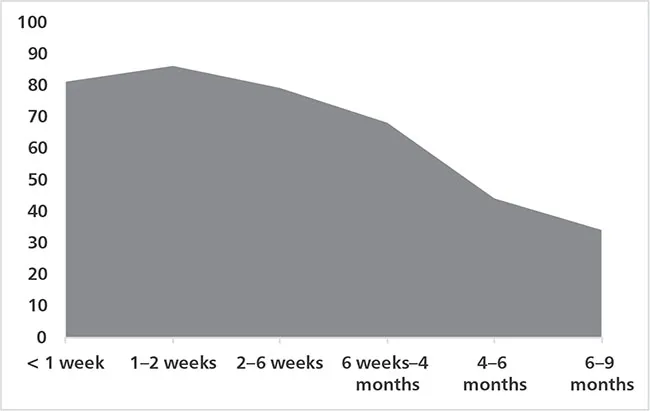

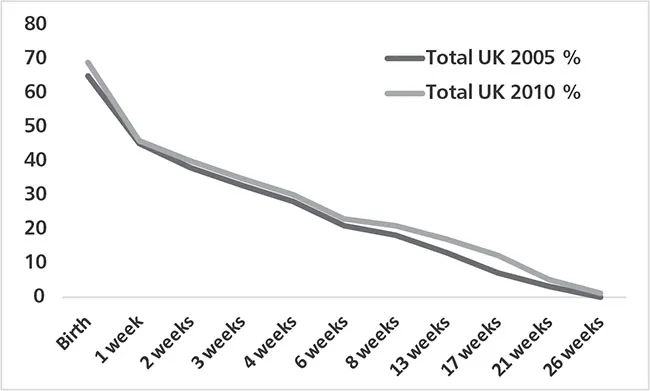

In 2005 the Infant Feeding Survey for the first time attempted to identify the duration of exclusive feeding (Bolling et al. 2007). In 2010, by one week, less than half of all mothers (45%) were exclusively breastfeeding, and this had fallen to 21% by six weeks. At six months, the optimal duration, levels of exclusive breastfeeding were negligible (<1%). There is a wide gap between what research says is the best way to feed babies and what happens. Much work is therefore still needed to meet the recommendations of the Acheson report if we are to improve the health of society by increasing rates of breastfeeding and improving the diet of infants.

In J...